Queer Identity in the Vietnamese Diaspora Complicated by Culture and Discrimination

The story was co-published with Nguoi Viet Daily News as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A still from the movie Tho

When Heather Muriel Nguyen first identified as non-binary and asexual, it wasn’t just a declaration of identity, it was an act of self-advocacy in a culture where queerness is often silenced.

Heather Muriel Nguyen (right) acted in her very own short film “Hex the Patriarchy.” (Photo courtesy of Heather Muriel Nguyen)

Now a 30-year-old Vietnamese American actor and filmmaker in Los Angeles, Heather is using their voice to reshape LGBTQ+ representation in Hollywood and carve out space for others like them - especially in a time of rising political hostility and deep-rooted cultural stigma.

In middle school, Heather, who was born female, was attracted to girls. But that soon changed.

“Later in college, I discovered I'm actually asexual - not sexually interested in anyone. I used to go by she/they pronouns, but I recently switched to using they/them exclusively," they explained.

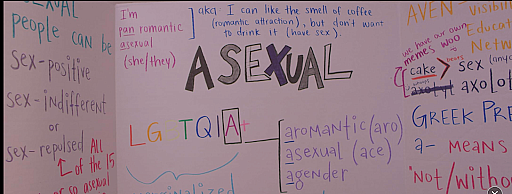

Heather struggled to find the correct term to describe their identity until they learned about the different nuances within the LGBTQ+ community. That’s when they found that the terms “non-binary” and “asexual” aligned best with their experience.

Creating their own representation

Heather has participated in various commercials and secured a few roles in Hollywood films - but the characters they were cast as often fell into tired tropes: the victim, the submissive Asian girl, the quiet, voiceless side character.

“I don’t see the representation for my sexual identity in Hollywood, and that motivates me to create stories that shine a light on the LGBTQ+ and AAPI community.”

Heather’s debut short film, “Tho,” inspired by their Vietnamese name and life as an asexual person, follows the character’s journey of healing and discovering romance as asexual individual. Released in 2021, “Tho” was both co-directed and led by Heather as a lead actor and can be watched on Vimeo.

Tho movie poster

“If there are no stories for us, we can just make them ourselves. No need to ask for permission, just follow your heart and dreams,” they chuckled.

In 2022, Heather wrote, acted, and produced “Hex the Patriarchy,” a fantasy teen comedy exploring demisexual and asexual identities. They also co-wrote and starred in the sci-fi short drama “Still Queer” in 2023.

Intergenerational gap within the LGBTQ+ Vietnamese community

Uyen Hoang, the executive director of VROC - Viet Rainbow of Orange County - states that loneliness, depression, and intergenerational trauma are a few of the reasons that are affecting the mental health of the LGBTQ+ Vietnamese community.

VROC is the grassroots organization that works with LGBTQ+ Vietnamese Americans and their loved ones through research, education, and advocacy.

“The language gap also is the major factor that affects the communication and acceptance within the families as the younger generation could not find the right wording to express their sexual orientation to their parents,” Uyen explained.

“Being queers in the Vietnamese community is difficult because of stigma. Finding the community to accept and support is challenging.”

Uyen also dealt with acceptance challenges of her own.

“I was in ‘the closet’ for a long time, hiding my true self to the world because my mom’s side is Catholic. I’m Catholic too.” She added “I would not come out if it was not for VROC. VROC gave me the support system and the courage.”

VROC members during the Tet Parade in Little Saigon, Orange County. (Photo courtesy of VROC)

Uyen’s mother was confused when she decided to come out as queer and her father was quiet.

“I did not choose to be your dad, you did not choose to be my daughter. We just choose to be good people,” Uyen’s father told her.

Uyen explained about her mother's thought process that she knows queer people but does not experience it as her faith is still the priority.

“My mom tried to understand but still wanted to stay true to her religion,” Uyen said.

VROC now has six staff and has almost 300 members. VROC is how the Vietnamese LGBTQ community finds strength in their chosen family.

The study of VROC in 2022 reveals how LGBTQ Vietnamese Americans are building resilient support networks to combat discrimination and cultural rejection. Through six months of research involving interviews with 15 members and observation of over 30 participants, the study found that chosen families within the organization provide crucial social support and belonging that counters the negative effects of homophobia.

The research identified three key themes: members actively redefine traditional family and kinship concepts to embrace both Vietnamese culture and LGBTQ identity, Vietnamese motherhood plays a complex nurturing role within the community, and social connectedness directly impacts mental health and wellbeing. These findings demonstrate how marginalized communities can create powerful support systems that preserve cultural heritage while fostering authentic self-expression and acceptance.

Uyen explained that VROC serves as a “surrogate family for members whose biological families struggle with acceptance.”

When LGBTQ Vietnamese Americans come out and face rejection from their own parents, older VROC members step into parental roles, offering emotional support and sometimes even opening their homes to temporarily provide safe housing and a stable support system.

The Asian immigrant queer community faces huge challenges

According to Gallup's most recent survey, nearly 1 in 10 American adults (9.3%) identified as LGBTQ+ in 2024, while the vast majority (85.7%) identified as straight. Among LGBTQ+ identities, bisexual was the most common at 5.2%, followed by gay (2.0%), lesbian (1.4%), and transgender (1.3%). Less than 1% identified with other LGBTQ+ terms including pansexual, asexual, or queer.

A UCLA study found that 27% of Asian LGBT non-citizens reported psychological distress, less than 5% of their non-LGBT non-citizen peers. More than one-third of LGBT non-citizens said they lacked a usual source of healthcare - more than double the rate of the U.S-born LGBT peers.

These statistics underscore the profound barriers Asian LGBT immigrants face: from poverty and food insecurity to limited access to health care and compounding psychological stress.

Vietnamese Americans make up 9% of AAPI LGBTQ youth, and with added challenges from language barriers and cultural stigma, they face a serious threat to both their physical and mental health at a pivotal political moment, according to the study from The Trevor Project.

Uyen says that the immigrant queer community is facing the biggest challenges in the current political landscape because of ICE (U.S Immigration and Customs Enforcement) raids and the restriction during travel.

Uyen Hoang (left), the executive director of VROC - Viet Rainbow of Orange County, with her partner. (Photo courtesy of Uyen Hoang)

Queer and transgender people can still travel under the Trump administration, but securing passports and other IDs that match their gender identity is difficult, increasing the risk of travel-related issues or harassment. Ongoing legal battles mean the situation could change with future court or administrative decisions.

On the county level, Orange County does not equip with resources for LGBTQ+ community in AAPI languages, according to Uyen.

“We are still struggling to advocate for research and studies for the queer community. The ongoing struggle is that the elected officials are not connecting with our minority community,” Uyen said.

“Orange County has a budget but little money goes toward the services to protect the rights of LGBT+ community.”

According to an article in Cardiology Advisor, the Big Beautiful Bill of the Trump administration proposes over $1 trillion in Medicaid cuts over the next decade, disproportionately impacting the LGBTQ+ community, especially low-income individuals and those living with HIV/AIDS.

These reductions will result in lost health coverage and diminished access to critical services, including HIV treatment, STI testing, and mental health support. The bill also limits federal funding for gender-affirming care and could bar states from providing such services through Medicaid.

About 21% of transgender individuals and 40% of people living with HIV depend on Medicaid. Many clinics offering mental health care, sexual health services, and gender-affirming treatment for LGBTQ+ communities also depend on federal funding to operate.

The Big Beautiful Bill was signed into law on July 4th, 2025.

Stigma within the Vietnamese community

Stigma toward LGBTQ+ individuals remains deeply rooted in many Vietnamese families and communities. For Heather, navigating this cultural terrain has been one of the hardest parts of their journey.

In Vietnamese culture, being queer or asexual is often viewed as a phase or something shameful.

“It’s hard when people assume you’re broken or that you’re just confused,” Heather Nguyen said.

Traditional values emphasizing traditional family roles, marriage, and filial duty often leave little room for LGBTQ+ identities. In particular, non-binary and asexual orientations are misunderstood or erased altogether by the traditional families.

Heather noted that elders in their community sometimes equate queerness with Western influence or mental illness, beliefs that isolate queer youth and silence conversations about identity and mental health.

“There was always this unspoken pressure to ‘be normal,’ to marry a man, to start a family,” they shared

The fear of disappointing parents or being rejected by one’s community leads many LGBTQ+ Vietnamese Americans to live in silence or double lives. For individuals who do come out, the journey is rarely linear and often filled with painful ruptures and slow rebuilding of relationships.

But change is possible.

“Younger generations are more open, and some older folks are starting to ask questions, even if they don’t fully understand,” Heather said. “That curiosity is where healing begins.”

Coming out and finding affirmation

Heather first came out to their father in middle school and was met with surprising acceptance. “My dad always kind of knew I was different,” they said. “He just said, ‘You’ve always been special.’”

In college, Heather opened up to close friends about being asexual. The rest of the family gradually began to accept their identity. As the oldest of three siblings, Heather’s journey has quietly opened the door for more dialogue and understanding at home.

“Having emotional support - from best friends, family, and peers helped me overcome so many internal battles and gave me the strength to keep going,” they said.

Heather also found support at the Yellow Chair Collective, a Los Angeles-based mental health center that offers LGBTQIA-affirming therapy and support, especially for Asian Americans.

“In 2024, I made the bold decision to cut my hair short for the first time,” they said, smiling. “That was the best thing I ever did. For the first time, I saw myself clearly, existing with short hair and feeling like myself.”

Through storytelling, advocacy, and community, Heather Nguyen and Uyen Hoang continue to challenge stereotypes and push for representation not just for themselves, but for every queer Asian American who has yet to see their reflection in the world.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.