Epidemic of Suspensions Poses Health Concerns

U.S. middle and high schools are more frequently turning to suspensions.

A new report released this week from the UCLA Civil Rights Project concludes that suspension rates in many U.S. middle and high schools are hitting alarming new highs.

The report, titled “Out of School and Off Track,” examined data on suspension rates from 26,000 U.S. secondary schools and found more than 2 million students were suspended at least once over the 2009-2010 school year — that’s one in nine students.

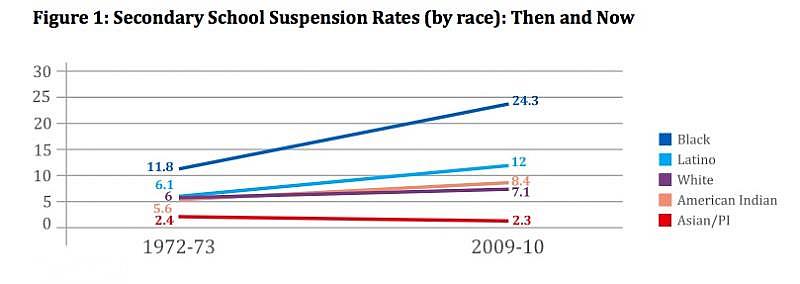

Researchers found some striking racial disparities as well: More than 24 percent of black students were suspended over the course of the year, compared to about 7 percent of white students and 12 percent of Latino students. By comparison, less than 12 percent of black students and 6 percent of Latinos were suspended over the course of the year in 1972-1973. For black male students with disabilities, the new figures rise even higher: 36 percent were suspended at least once during the year. The majority of the suspensions followed relatively minor offenses such as tardiness, violating the dress code or disrupting class, the study reports.

But what does this mounting epidemic of suspensions have to do with health? A lot, according to a whole field of research that says education is a key predictor of health outcomes later in life.

Patrick Krueger, a sociologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, who studies the social determinants of health, told a room full of health reporters last year that education is one of the best predictors of how long you’ll live and how healthy you’ll be. As Krueger put it:

Education is something that sticks with kids over their entire life. It pays dividends for years and it also does all the nice things we like when it comes to economic development, allowing folks to have opportunities for higher income, to move into nicer neighborhoods or to improve their own neighborhood.

New research published last year found big differences in life expectancy as education level varies. Sarah Kliff, covering the findings for The Washington Post’s Wonkblog, wrote:

We know that education has a big impact on earnings and the ability to find employment. It also turns out to have a huge influence on how long Americans live: White men with less than a high school diploma had a life expectancy 12.9 years shorter than those with 16 or more years of education, according to new research in the journal Health Affairs. For women, the life expectancy gap stands at 10.4 years.

While it can often be difficult for journalists (and researchers) to separate out correlation from causation, there is growing evidence that education isn’t just a proxy for another variable such as income. The research suggests it’s not just that higher education is more likely to lead to a higher income and therefore better health. As economists David Cutler of Harvard and Adriana Lleras-Muney of Princeton wrote in a 2006 report scrutinizing the link between education and health, education often changes how we think and the choices we make:

The obvious economic explanations – education is related to income or occupational choice – explain only a part of the education effect. We suggest that increasing levels of education lead to different thinking and decision-making patterns.

If educational attainment is something that has been shown to have life-long and life-altering consequences, what does this spate of suspensions mean for students who are being taken out of class longer and more often?

The UCLA study suggests suspensions often worsen the plight of troubled students:

Research demonstrates that higher suspending schools reap no gains in achievement, but they do have higher dropout rates and increase the risk that their students will become embroiled in the juvenile justice system. Research also indicates that the frequent use of suspensions could be a detriment to school and community safety because it increases student disengagement and diminishes trust between students and adults.

Nor does a student necessarily need to rack up multiple suspensions to increase the drop-out risk, said Daniel Losen, one of the report’s authors:

One of the research papers we commissioned shows that being suspended just once in grade nine correlates to a doubling of the dropout risk from 16 to 32 percent. Further, the Centers for Disease Control has stated that out of school suspensions exacerbate a whole range of issues that poor families may be struggling with. Finally, the group at greatest risk is consistently students with disabilities. Some of these are students with mental health needs, others are learning disabilities, some have emotional disturbance, all are at significant risk for being suspended where often there is no guarantee of adult supervision — that is a huge concern.

If higher suspension rates lead to higher dropout rates, then U.S. schools’ over-reliance on suspensions could pose adverse health consequences for these students – and community health systems – down the road. The suspensions disproportionately hit minority students. And they already are far more likely to live in low-income communities suffering from chronic disease epidemics.

Losen and his co-author Tia Elena Martinez suggest that it’s time to reexamine how schools mete out discipline as well as the low bar many schools have for triggering suspensions. Better disciplinary alternatives exist, they argue.

Pointing to racial disparities in the data and to “recent actions by the U.S. Department of Justice and the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights,” Losen and Martinez suggest that “it is not only unjust to continue the status quo, it may be unlawful.”

To review the spreadsheets with suspensions data for a wide range of districts, visit the Civil Rights Project.

Image by Paul Lowry via Flickr.