As School-Based Health Centers Gain Following, Funding Is Key

To listen to Alex Briscoe talk about school-based health centers is to hear a man on a mission. As director of Alameda County’s Health Care Services Agency, Briscoe has shepherded a major expansion of school health centers, which he sees as one of the most effective ways of improving the well-being of underserved communities.

Alameda County is a vanguard in California when it comes to school-based health centers, which typically provide on-campus primary and mental health services as well as counseling, preventive health, health education and safety-net benefits enrollment. With La Escuelita Education Center celebrating the official opening of the Youth Heart Health Center in Oakland Thursday, the county can now boast of 28 school health centers. That compares to about 200 such centers statewide, or nearly 2,000 nationwide.

Three years ago, Oakland Unified School District had seven school-based health centers; today they have 15. “We have a relatively simple premise,” Briscoe said. “We intend to make Oakland Unified the first district to guarantee primary care as a function of enrollment.”

Oakland’s rapid expansion of school-based health centers is part of a larger movement. Advocates of the school-based approach say that providing physical and mental health services in schools makes it far easier for students to access care they might be unable or afraid of seeking elsewhere. That care can improve student attendance, performance and graduation rates. Those rates, in turn, are closely linked with health outcomes that play out over a lifetime.

Richard A. Carranza, superintendent of the San Francisco Unified School District, penned an op-ed last month spelling out how his district’s health centers were making measurable gains:

During the 2011-12 school year, Wellness Centers offered support groups to high school students who were experiencing trauma, grief or loss. At the start, more than 90 percent of them reported symptoms that put them above the clinical range for post-traumatic stress disorder. After taking part in the support groups, that number of students with PTSD was reduced to 44 percent.

A 2009 study in the Journal of Adolescent Health found significant increases in attendance and GPA gains for school-based health center users compared to their peers. Another study found that the centers significantly reduced emergency room visits.

Rallying the funds

The biggest challenge facing many school-based health centers is the lack of a stable source of funding. Most centers rely on a shifting hodgepodge of local, state and federal funding in combination with insurance reimbursements, Medicaid, grants and philanthropy.

In Alameda County, 75 percent of center funding comes from reimbursements for services, often for programs like Medicaid.

But the financial health of many such centers can be fragile. And many public health and education leaders would like to change that.

In April, more than six-dozen school superintendents and principals from across the country signed a letter sent to Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa) and Rep. Jack Kingston (R-Ga.) – chairs of the Senate and House Appropriations Subcommittees on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies – requesting $50 million in the 2014 budget for school-based health centers. The California School Health Centers Association estimates that California would receive $8 million if the funds were appropriated.

In making its case, the letter states:

Several studies have shown that the barriers experienced in traditional mental health settings – stigma, non-compliance, inadequate access – are overcome in school-based settings. In studies of SBHC service utilization, mental health counseling is repeatedly identified as the leading reason for visits by students.

High school SBHC users in one 2000 study had a 50 percent decrease in absenteeism and 25 percent decrease in tardiness two months after receiving school-based mental health and counseling.

While the Affordable Care Act provides $200 million for fiscal years 2010-2013 to fund school-based health centers, that money is designated for construction or renovation, not operating expenses. An additional $50 million is included in the ACA for operating costs but that sum hasn’t been appropriated yet.

Problems primary care can’t address

Briscoe’s own faith in school-based health centers is informed by his first-hand experience running one. Before he joined the county, he served as director of the Chappell Hayes Health Center at McClymonds High School in West Oakland. In the first year, there were 42 graduates from the high school; the following year the tally rose to 100. Briscoe says the clinic helped students make those gains by bringing in $850,000 for a suite of additional school programs on topics ranging from nutrition to dealing with trauma in a violence-plagued pocket of the city. “We increased the resources available to that school by a third,” Briscoe said.

School-based health centers help address challenges that traditional primary care hasn’t been able to address. Pointing to the three leading causes of death among adolescents – accidents, homicide and suicide – Briscoe said, “The things young people need access to isn’t covered by primary care. These are not things doctors treat.”

The services most in-demand by students in underserved neighborhoods are behavioral health, reproductive health and health education -- areas where a school-based health center can really shine. “Young people are brilliant when given good information.”

School health centers also harness the power of peer networks in spreading critical health information. “When you look at our 28 clinics, the ones that are strongest are the ones with the peer health education programs,” Briscoe said. Students who serve as peer counselors can help classmates to overcome stigma and fear about seeking help. They can broach sensitive health topics, and combat misinformation in ways that adults or “outsiders” can’t always do.

“School-based health centers can … free schools to do what they should be doing – focusing on education and child development,” said Briscoe.

Raising awareness

Despite their appeal, school-based centers don’t usually end up as a focal point for local journalism. One reason: the centers’ work falls into a gray area when it comes to traditional education and health beats. While every reporter and reader know what a school nurse does, far fewer are familiar with full-service school health centers.

Briscoe argues that it’s a story worth a deeper look.

“We have to change the discussion about what health care access is,” Briscoe said. “It’s a basic human right: Access to the right care at the right time at the right place.”

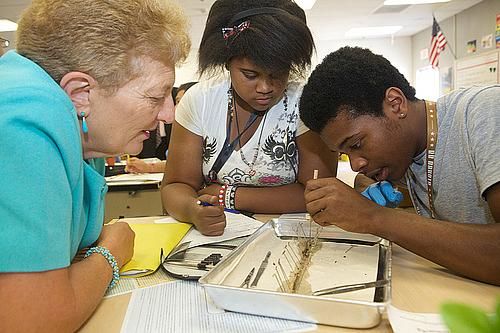

Image by U.S. Department of Education via Flickr