Predictive Prevention: Could health care make good use of consumer data?

When Charles Duhigg explained in the New York Times in February 2012 how Target could with some degree of reliability predict whether your teenage daughter was pregnant and send her anticipatory diaper coupons – even if you didn’t know that she was pregnant – there was a lot of hand wringing in the media about how much companies know about us.

This is known as “predictive analytics.” It was standard practice then and even more so now. (It is so standard that Predictive Analytics World conferences have been held in near-constant rotation around the world since 2009.)

Despite the outcry, Duhigg’s article did not change the way companies act.

In fact, many people have come to rely on the way companies personalize our experience based on past purchases and practices. We expect that we will see ads for things we bought on one website displayed on a different website, even if we are visiting it for the first time. We allow Google Maps to access all kinds of information about us so that it can tailor our navigation routes on our smart phones. We look forward to notifications of “deals of the day” that seem to be discounts made just for us by our favorite brands.

And yet we are about to enter another Target-knows-your-daughter-is-pregnant controversy. But this time, something might actually change because the subject isn’t just companies trying to send you coupons. This time the subject is health care, and, for whatever reason, health care always makes the temperature of debate rise. Instead of “death panels,” we may soon be hearing about “health police.”

The kickoff for all this was an article by Shannon Pettypiece and Jordan Robertson of Bloomberg BusinessWeek. In “Your Doctor Knows You're Killing Yourself. The Data Brokers Told Her,” they wrote:

You may soon get a call from your doctor if you’ve let your gym membership lapse, made a habit of picking up candy bars at the check-out counter or begin shopping at plus-sized stores. That’s because some hospitals are starting to use detailed consumer data to create profiles on current and potential patients to identify those most likely to get sick, so the hospitals can intervene before they do.

If you wonder why I think this one might cause more of a flare-up than Duhigg’s piece, consider that even though the Target article ran in America’s most influential newspaper, it has generated 570 comments since February 2012. The BusinessWeek article has been up for all of two weeks and had generated 974 comments as of Friday.

It’s worth noting that data mining expert Gregory Piatetsky recently asked on his influential KDnuggets site whether Target really did figure out that a teenager was pregnant or just got lucky and sent diaper coupons to a pregnant teen. Or unlucky. The controversy certainly put Target on the defensive.

If the controversy this time completely kills this health care experiment before it has produced any results, we may be missing an important opportunity. Concerns about privacy and how much companies profit from your personal data are all legitimate and worthy of discussion.

But pause to think about what’s happening here. Health care providers are looking at ways of using your digital history to do something more than just increasing the odds that you buy something you may not need. This doesn’t mean their motives are entirely pure. Sure they want to save hospitals, doctors, and insurance companies money. But health care is one of those areas where many of the costs do tie directly to your behavior. Understanding that behavior better in order to address it before it becomes a chronic or fatal condition could actually have many short- and long-term benefits. Whether health care providers can actually pull it off is another question. I’ll explore what they have working for them and against them over a few posts.

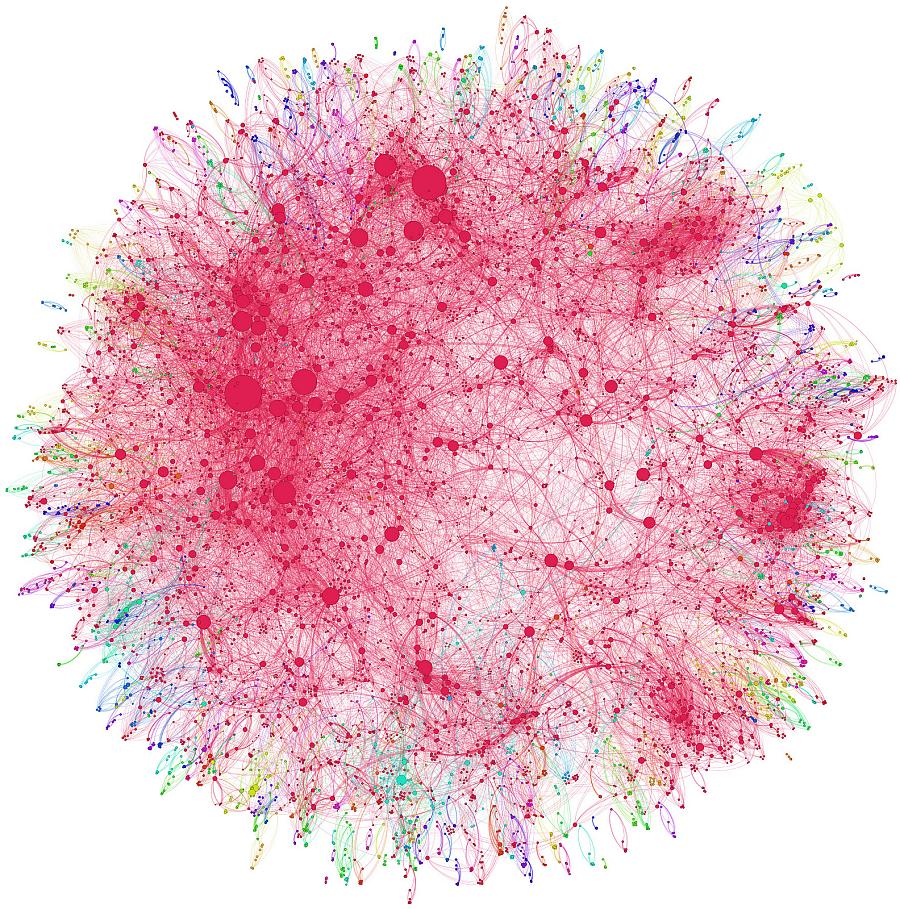

Photo by Andy Lamb via Flickr.