You Win Some: Teaching Health Journalism to Kids

After a long day's work as a dental assistant, Musette Jackson is captured on video sitting comfortably in a worn leather chair that barely hides the scuffed walls of her front porch. Still in her work scrubs, the Greensboro, Ga. native speaks of a common problem confronting dentists practicing in rural areas: tooth decay. Jackson tells the interviewer in her lyrical Southern drawl how many people she's seen lose their teeth. Most don't know how much decay they have until it's too late; there's nothing to be saved.

Complete with dialect, a revealing setting, and a conversation about real-world issues, the video footage has all the makings of riveting journalism. With his baritone voice, the reporter continues his interview.

Suddenly, the porch screen door slams. Cars rushing by leave a distracting trail of noise. The shadows darken Jackson's face just a tad too much. The blare of a television inside the house suddenly drowns out the pleasant sound of the birds - and Ms. Jackson's words.

You win some and you lose some.

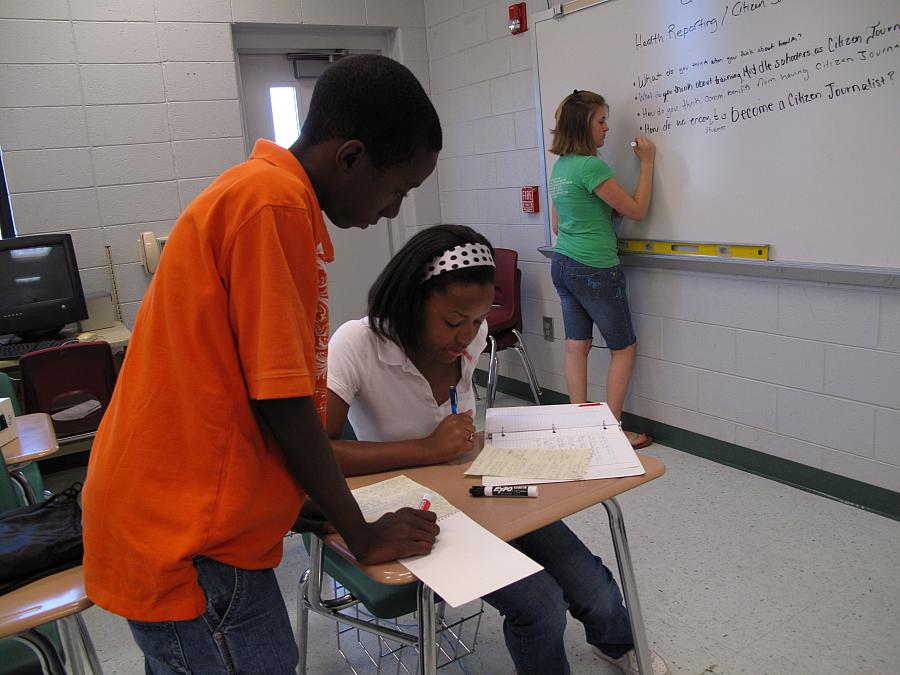

The reporter with the booming baritone is a 12-year-old participant in "Greene County: A Picture of Health from Our Youth," a youth media program for middle school students in rural Greene County, Georgia, hosted by the Health and Medical Journalism Program at the University of Georgia. It teaches them how to research and report on health issues affecting their families, neighborhoods and school. The telling commentary in this student's footage - along with the technical flaws - illustrate the learning process that took place for both students and instructors as HMJ piloted its first youth journalism project.

Building Confident Reporters

Youth media programs can boost self-confidence, develop media literacy skills and empower youth by giving them the opportunity to be heard, says Ingrid Dahl, editor in chief of Youth Media Reporter. In our program, youth also gained new insights about common health concerns in rural areas, the impact of unhealthy habits and the issues concerning their peers the most. The students also learned about the roles of various healthcare practitioners and where to find them in their community.

Youth media programs can boost self-confidence, develop media literacy skills and empower youth by giving them the opportunity to be heard, says Ingrid Dahl, editor in chief of Youth Media Reporter. In our program, youth also gained new insights about common health concerns in rural areas, the impact of unhealthy habits and the issues concerning their peers the most. The students also learned about the roles of various healthcare practitioners and where to find them in their community.

Youth trained to produce their own health stories develop a better understanding of how health coverage is shaped, says Donna Myrow, founder of L.A. Youth, a citywide youth newspaper which opened its doors in 1988. They become engaged news consumers, developing a critical eye. Youth journalists may even become regular readers of - gasp - newspapers, albeit online. When they set out for college some will inevitably choose career paths outside of journalism while others enter journalism school with impressive skills.

Youth media journalists can also get stories that professional journalists can't because of their unique sensibility and community ties.

The benefits are real, but they don't come easily. As our youth media educator team learned in the summer of 2009, there are plenty of places to stumble. Here are a few tips we learned from our first summer teaching middle school students, and some youth journalism resources.

The principal at our school site was charming, and, to our youth journalists, an intimidating authority figure. The combination made him a daunting interview for a young woman just coming into her own. Only 10 minutes after one of our star reporters set off to interview him about health challenges at her middle school, she returned, demoralized. "I got nervous," she told me. As Dahl points out, this is a common issue when working with youth journalists. It's about "building confidence to stand your ground as an expert, and own that you are an expert."

In teaching students how to interview, we asked them to talk with family members and peers first and health professional and experts last. Peers proved to be the most difficult. The footage often turned out to be little more than a series of outtakes where both the interviewer and interviewee dissolved into preteen laughter. The interviews of professionals were also difficult. To combat their nervousness, students spent hours with us, preparing. We also supported them as they researched their topics and developed questions.

We also tried to make the young people feel like professionals by outfitting them with reporter's notepads and press pass-style badges. The hope was that these items, and the preparation, would help members of our news team feel confident.

To our surprise, the professional make-over didn't just help the kids. It also worked its magic on adults too. "When you have a recorder, and a microphone, and a headset on," says Judy Goldberg, founder of Youth Media Project in Santa Fe, N.M. "there's something that happens just because of that costume People do take the kids more seriously."

Practice Matters and Spontaneous Surprises

We elected to use FlipCam video technology for our shoots. It's simple to use and results in high-quality footage. We trained the students to look out for distracting sounds, bright windows, dark corners or heads that disappeared beyond the camera's reach. We also knew they would need practice to strengthen skills.

While there were plenty of gaffes, what we didn't anticipate was how good these novices could be. We soon learned that each time one of the students picked up a camera and aimed it at a family member or classmate, there was potential for footage that would be subtly amazing. Whether it was the natural banter of friends talking about exercise or images revealing living conditions, we almost always wanted to keep it. Even when the shooting assignment was merely for practice, the footage could be used as b-roll.

We spent hours of class time with students listening for background noise, or looking out for bouncing images and poor lighting. From our shared critiques they became aware of how ambient noises, lighting or placement of their interview subject could jeopardize their footage. "What do you hear that is disruptive," we asked our youth journalists? "What draws attention away from the main subject? How can we fix it?"

Getting There is Half the Journey

Poor transportation hindered us throughout our summer program. Our rural county has no public transportation. As middle school students, the youth reporters depended on older family members for rides to and from interviews and to the program's home at their middle school. As a result, attendance was sporadic. Our pilot program began small with about 10 students enrolled. There were days when most enrolled youth were present and others when our numbers dwindled to two or three.

To support those students who were unable to attend regularly we started emailing, calling, and even texting – whatever worked best. We checked in with students who couldn't make it to class to ask if they were having any difficulties and to get an update about how much footage they had captured. We were able to brainstorm with them remotely about sources and interview questions.

Other youth media programs have had to come up with creative ways to contend with transportation challenges. At Youth Media Project, youth reporters are responsible for research, interviewing and production of the radio broadcasts. Goldberg says that in the city of Santa Fe, the bus system runs infrequently, so adult staff often give rides to the teen reporters who can't drive. At the youth media programs Dahl leads in New York, middle schools students receive free metro cards and rely on public transportation.

We also were able to make headway, despite the transportation and resulting attendance problems, because we didn't try to have our youth reporters take on the final stages of production. We had the youth reporters focus on learning the fundamentals of researching and reporting health issues. They would return with their raw footage and a member of our program team completed the archival and editing process.

Teen-Friendly Newsrooms

Young people don't look kindly upon sitting through a two-hour lecture, especially during summer break or after a full day of school. When mentoring youth, charisma is as important as journalism smarts. If you or your news organization has an interest in starting a health journalism program for youth, you may want to collaborate with a local youth development organization. In our collaboration between the journalism school at University of Georgia and a local school system, "visiting experts" taught the students. I drew upon my background as a former middle school teacher to plan the instruction and daily programming.

Marona Graham-Bailey is a certified special and general education teacher and a graduate of the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication MA program at the University of Georgia.

Photos: Health and Medical Journalism at UGA