The Power of Small Data: Brace yourself for the data-doubters

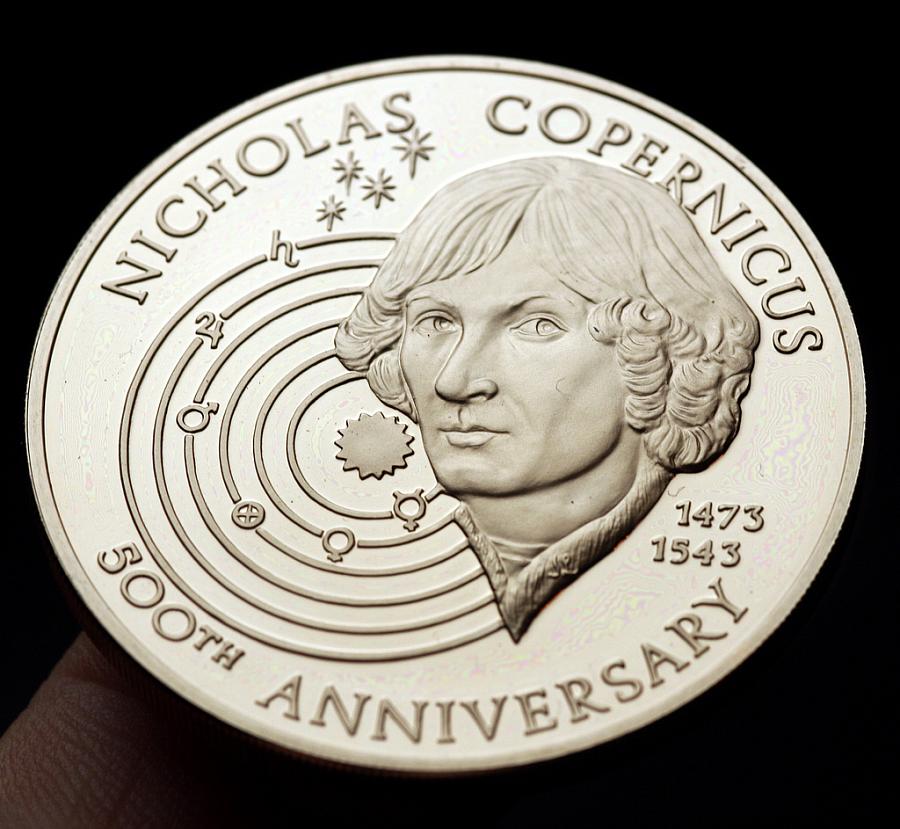

Nicolaus Copernicus never visited the sun.

He did not visit the moon or any planet in the solar system. In fact, Italy was about as far as he traveled from his native Prussia in all of his 70 years.

And yet his mathematical equations and drawings of our universe became the basis in 1543 for the modern conception of a sun-centered universe. No one traveled to the sun – or anywhere outside of Earth – for the next 425 years. And yet, the idea that the Earth revolves around the sun became an established fact that is now one of the basic underpinnings of our understanding of the universe.

We believe it so uncritically that we also believe all kinds of other things about the sun itself, like the thickness of its surface, the temperature of its core, and the amount of energy released by a solar flare.

Here’s Frank Ahrens writing in the Washington Post:

The sun, like all stars, is a nuclear reactor. At its core, the sun's temperature is estimated at 27,000,000 degrees. (Phew!) At the surface — not a solid surface, really, but a gaseous shroud — the temperature is a much cooler 10,000 degrees.

Has anyone ever visited the sun to take its temperature? No. No one has even come within 90 million miles of the sun.

And yet, we trust that Ahrens is right and that all the scientists who have told us over the years about the various measurements related to the sun are right. We trust them because we know that they are making the best estimates based on the best available data. Most numbers you see related to health and economic trends are estimates, too. When someone writes that “every three seconds” someone dies of hunger, that’s an estimate. When someone writes that 40 percent of the unemployed “have quit looking for jobs,” that’s an estimate.

People accept these types of estimates all the time. Except when you write something they don’t like. So remember the example of Copernicus when you build your own database for your reporting, because you very likely will be criticized. Here are some of the most common critiques:

- You are just a reporter and could not possibly have the content knowledge necessary to understand the topic to the depth necessary to build and analyze a database about it.

- You are taking data from different points in time, different places, and different conditions that cannot and should not be pieced together.

- You are overlooking nuances that cannot be found in the data alone and you need to understand the broader context for the story that you think you found in the data.

- Your analysis is too simplistic.

- Your analysis cherry picks the data to create the story you want to create.

And always, always, always someone will say that you left a piece of data out of the equation. This came up recently when the Wall Street Journal tallied up the cost of many of the programs that Bernie Sanders would like to see funded by taxpayers – tuition at public universities and universal health care among them – and arrived at a whopping $18 trillion over 10 years. Reena Flores at CBS News wrote:

When it comes to the $18 trillion price tag put forth by the Wall Street Journal analysis, Sanders countered that the newspaper didn't take into account private health care plans. ‘What the Wall Street Journal said was that included 15 billion dollars for national health care programs,’ the Democratic hopeful said. ‘What they forgot to say is that you would not be paying – and businesses would not be paying – for private health insurance.’ He fired back at the newspaper with harsher words on a later appearance on CBSN, saying their prediction was ‘wrong. It was inaccurate. That's what the Wall Street Journal does.’

Sanders’ criticism was to be expected. He could attack the Journal for making an estimate, which is what the Journal did. And Sanders was doing the same thing, making an estimate. To make your estimates more than just fodder for a he said/she said debate, there are many things you can do to make them stronger. I’ll write more about that in a future post.

Next: How to beat back your data-doubting critics.

[Photo by Kevin Dooley via Flickr.]