Reporting the findings: Absolute vs. relative risk

Why you should always use absolute risk numbers:

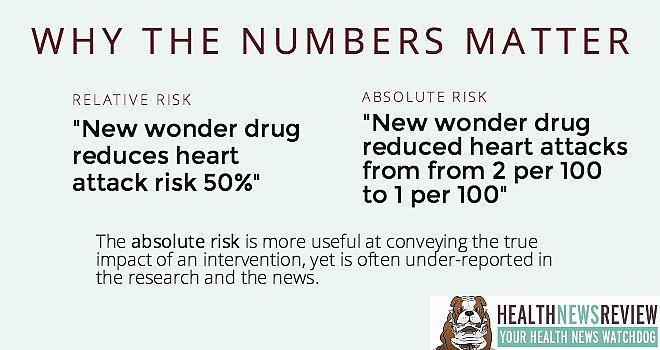

“New drug cuts heart attack risk in half.”

Sounds like a great drug, huh?

Yet it sounds significantly less great when you realize we’re actually talking about a 2% risk dropping to a 1% risk. The risk halved, but in a far less impressive fashion.

That’s why absolute numbers matter: They provide readers with enough information to determine the true size of the benefit. In more detail:

If the 5-year risk for heart attack is 2 in 100 (2%) in a group of patients treated conventionally and 1 in 100 (1%) in patients treated with the new drug, the absolute difference is derived by simply subtracting the two risks: 2% – 1% = 1%.

Expressed as an absolute difference, the new drug reduces the 5-year risk for heart attack by 1 percentage point.

The relative difference is the ratio of the two risks. Given the data above, the relative difference is:

1% ÷ 2% = 50%

Expressed as a relative difference, the new drug reduces the risk for heart attack by half.

Steve Woloshin and Lisa Schwartz of the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice

explain absolute-relative risk in a creative way. They say that knowing only the relative data is like having a 50% off coupon for selected items at a department store. But you don’t know if the coupon applies to a diamond necklace or to a pack of chewing gum. Only by knowing what the coupon’s true value is–the absolute data–does the 50% have any meaning.

A good example of reporting risks

In our review of a STAT story on new aspirin guidelines, we praised them for using both absolute and relative numbers. Here’s what the story said:

In a meta-analysis of the six major randomized trials of aspirin for primary prevention, among more than 95,000 participants, serious cardiovascular events occurred in 0.51 percent of participants taking aspirin and 0.57 percent of those not taking aspirin. That corresponds to a 20 percent relative reduction in risk. At the same time, serious bleeding events increased from 0.07 percent among non-aspirin takers to 0.10 percent among those taking aspirin, or a 40 percent relative increase in risk.

This inclusion of absolute numbers helps readers get a much better sense of the overall differences we’re talking about here.

And a not-so-good example

In our review of a news release from the National Institutes of Health, we called them out for only using relative risk reductions from a study about intensive blood pressure management.

The release points out that those study participants whose blood pressure goal was 120 mm of mercury had 33 percent fewer cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks or heart failure, and had a 32 percent reduction in the risk of death, compared to those participants with a higher goal.

But these numbers don’t tell the whole story. It should be noted that these relative reductions correspond with absolute risk reductions of only about 0.8 to 1.3 percentage points — reflecting a number needed to treat (NNT) of roughly 100. In other words, approximately 100 people need to be treated to this target in order for 1 person to experience an improved outcome. The other 99 don’t benefit but have the potential to experience adverse effects.

The problem often starts at the research level

While absolute numbers are essential, they also may be hard to find. Research has shown that they’re often missing from study abstracts in medical journals, according to the Harding Center for Risk Literacy. The relative figures then find their way into news releases, health pamphlets and in news stories, the center explains, which only tells part of the picture.

When this happens, the onus is on the journalist to push for absolute numbers from the researchers, or get help from a third-party expert to assist with the calculation. While this adds more work, it is significantly more informative and helps diminish misleading claims.

More: Harding director Gerd Gigerenzer argues this is a moral issue.

Watch out for ‘mismatched framing,’ too

The problem doesn’t end there, though. The Harding Center also reported that medical journals often publish studies that have what’s known as “mismatched framing:” The benefits are presented in relative terms, while the harms or side effects are presented in absolute terms. Why?

“The absolute risk looks small, so it gets used for the side effects,” said Harding’s head research scientist, Mirjam Jenny. “I think that is very much on purpose–I don’t think that happens by accident.”

In other words, study authors want the benefits to look bigger and the harms to look smaller. This mismatched framing often gets picked up by journalists who report on the study. Yet it’s the patient who much make decisions based on this lopsided information.

The bottom line

Absolute risk vs relative risk: Each may be accurate. But one may be terribly misleading. If your job is marketing manager for the new drug, you are likely to only use the relative risk reduction. If your job is journalist, you would serve your readers and viewers better by pointing out the absolute risk reduction, and making sure you don’t echo any mismatched framing.

And if you’re a news consumer or health care consumer, it’s wise for you to be skeptical and ask “of what?” anytime you hear an effect size of 20-30-40-50% or more. 50% of what? That’s how you get to the absolute truth.

This article was originally posted on HealthNewsReview.org and is republished here with permission. (Photo by Metaloxyd via Flickr.)