Persistence leads reporter to Newark’s pandemic stories, despite early failures

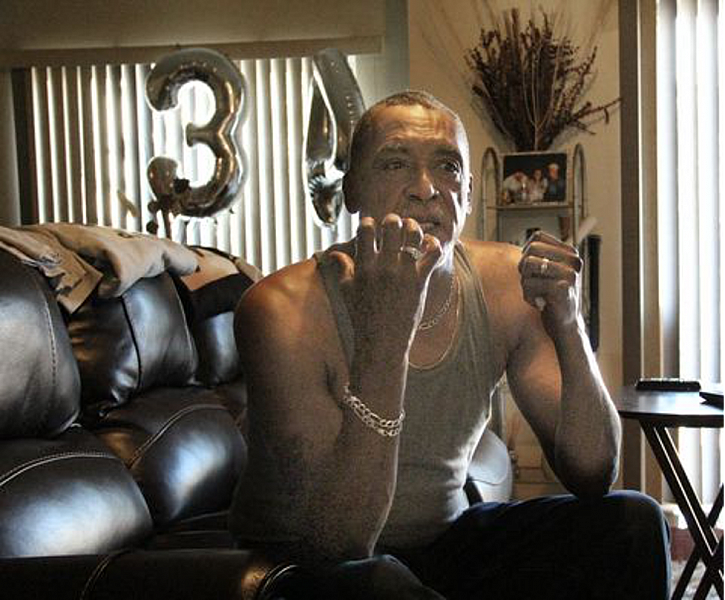

Walter Andrews, 65, was one of the Newark residents profiled in the story. Andrews is shown here in his home in September, several months after he lost his wife, daughter, father-in-law and brother to COVID-19.

(Photo by Spencer Kent/NJ Advance Media)

Weeks passed searching for a COVID-19 survivor or a family member of someone who had died from the virus in Newark, New Jersey.

While the pandemic posed obstacles, it wasn’t only the constraints of social distancing that presented challenges. Gaining trust within the community was a large obstacle that needed to be overcome.

When I began this project, it was important to explore this period of the late 1960s through the present day to bring the COVID-19 pandemic plaguing the city into context — exploring the city then and now, and identifying the social, economic and racial disparities that contributed to Newark suffering the most deaths of any municipality in New Jersey.

Newark is a dynamic city, often misunderstood and known for many reasons — as a major hub of the industrial revolution and the nerve center where most of New Jersey’s transportation networks come to a head. But perhaps its most defining characteristic is the 1967 uprising.

I came into the project with few sources in the city. I was conscious of my identity as a white male and my lack of historical knowledge — knowledge I knew I would need to connect the dots.

Before I spoke to anyone, I wanted to get as familiar with the history of the city as I could. I purchased as many books on Newark as I could find, with topics ranging from its Puritan roots and the 1967 rebellion to locals and activists who helped shape the city. It felt necessary to understand the ways in which the city has been evolving as a whole. I felt it would give me confidence, knowing as much as I could about the city in which I was covering, helping me deepen relationships with residents.

I spent weeks canvassing neighborhoods, going door to door, trying to get people to speak to me. Sometimes I had success, but most times I came home with nothing after an eight-hour day.

I’d try one neighborhood that I knew had high rates of COVID-19 deaths, spending hours and hours without adding much to my notebook. I’d try another enclave and then another with the same failed outcome. It wasn’t that people weren’t answering the door. It was that the people who answered didn’t know (or trust) me, and I didn’t yet have a good reason why they should.

Meanwhile, I’d been conducting interviews with community advocates — some who’d been present in the city during the ’67 rebellion — and who were accustomed to speaking with reporters. I shared with them my struggle to find residents who would talk to me.

There was one community leader I was put in touch with while visiting an event where meals for the community were packaged to be sent out. The community leader ended up becoming my guide, putting me in touch with one resident. Then two. Then three. I realized the true mechanics of building relationships and trust. They didn’t come from reading books and proving what I knew. It came from being invited into a broader network of a community.

Despite the months I spent on research — my search for subjects, interviewing historians and experts, going to food distribution events, walking neighborhoods — most of my core reporting didn’t come together until the final weeks of my project.

There were plenty of anxious moments where I felt it would never come together; I’d hit a dead end. These moments came when I struggled to obtain the data I needed to tell my story, or lost touch with residents I had spent hours interviewing when they no longer answered my calls.

My colleagues and editor were incredibly helpful, reminding me to just keep going. Keep speaking to residents. Keep listening to their stories. Keep following the data. My group of 2020 National Fellows also played a huge role, and when I learned that they too were encountering these same challenges, it was comforting to work through our reporting obstacles together — workshopping ideas and brainstorming different ways to overcome the roadblocks.

Little by little, I began answering questions and finding more subjects, sometimes at random, who ended up being critical. I was invited to a prayer call with many of the pastors in the city, a weekly event where scripture was read and songs were sung by religious leaders of all denominations. I was welcomed to listen in and ask if anyone was interested in being interviewed or if they had members of their congregations I might be able to speak to.

The next day I got a few bites, and over the next few days and weeks, I conducted multiple interviews with pastors, activists and residents throughout the community. One interview emerged with a pastor of a church who had lost 15 congregants to COVID-19 over several weeks.

I also was put in touch with a 65-year-old city resident who lost his wife, daughter, father-in-law and brother to the virus. I sat down with him in his home, as he described in detail how the coronavirus swept through him home and left him by himself.

I spoke with a city activist who became a vital source in describing Newark during the ‘80s, ‘90s and early 2000s, and the ways in which the city has changed since then. She also revealed painful moments of her past while growing up in Newark, including the loss of her father as a child after his body mysteriously washed up on the beach in Brigantine, New Jersey, in 1981, abandoned more than 120 miles from home. She revealed personal traumas that had left many scars.

Another city activist described in detail what it was like to live during the 1967 uprising. And how far the city has come, which he attributed to Newark’s unique resilience.

I met with funeral home directors who described the horror they saw — the overwhelming number of bodies that flooded their businesses during the height of the pandemic.

Finally, I was getting somewhere. My ultimate goal in writing this story was to offer a nuanced picture of the city and its residents — to deliver something more insightful than the simplified stories so often written about Newark that only focus on crime and corruption. These facets were still part of the story, but they were far from the complete picture.

I wanted to tell the stories of the people of Newark who had suffered so immensely during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic — stories so intrinsically tied to socioeconomic, health and racial factors often overlooked in daily headlines.