What surveys tell us about how to boost vaccination rates in LA and beyond

A mobile clinic vaccinates Central American Indigenous residents in Los Angeles in April.

(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

As a nation, we’re now grappling with a new dilemma – COVID-19 supply has increased dramatically, yet less than half of the country is fully vaccinated. In late April, California public health officials worried about a declining vaccine supply in some counties. Now they worry about how to get an ample stock of vaccine into the arms of the remaining eligible but unvaccinated Californians.

Los Angeles County is a microcosm of the country because of its size and diversity. Its vaccination rates are quite similar to that of California and the U.S. Likewise, broader disparities show up here too, with white and higher-income Angelenos more likely to be vaccinated compared to African American, Latino and lower-income residents.

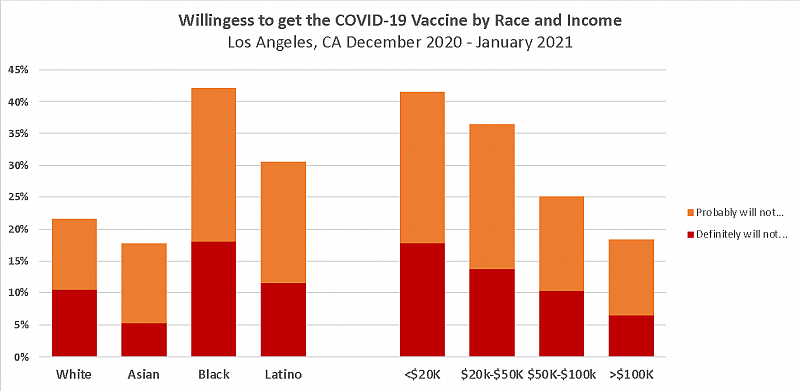

To better understand the challenges facing the vaccine push in Los Angeles County, we conducted an online survey of nearly 2,000 residents in December 2020 and January 2021, at the height of the pandemic and immediately after the first vaccine was authorized. We took steps to ensure the volunteers who filled out our online survey were representative of the population in Los Angeles, and we also weighted their responses to match 2019 American Community Survey demographic data.

(Source: Saluja et al. Disparities in Covid-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Los Angeles After Vaccine Authorization.)

Our results suggested that vaccination rates would be lower in the same communities hit hardest by COVID-19. Such findings weren’t exactly surprising, since multiple surveys from early in the pandemic found widespread concerns about the COVID-19 vaccine among racial and ethnic minority groups and lower-income persons.

The survey suggested the problems weren’t about just about access to health care. Even after controlling for having insurance and a health care provider as well as other social and economic factors, Black, Latino and low-income residents were two to three times more likely to say that they probably or definitely would not get the vaccine compared to white and higher-income residents. But there was an important caveat: Overall, only 11% of residents in our survey said they would “definitely” not be willing to get the vaccines, suggesting that most might reconsider.

As we’ve seen with national surveys, most vaccine hesitant residents were worried about vaccine side-effects. Another important factor was comfort using online technology. Respondents who reported low levels of comfort with being able to do things online were significantly less likely to say they would get vaccinated.

Other barriers, such as limited transportation and difficulty taking time off work, also likely explained lower vaccination rates in many communities. Our survey found that racial and ethnic minorities and low-income residents were significantly less likely to be able to take off work while awaiting their COVID-19 test results, suggesting similar factors are at play with vaccines. Vaccine hesitancy in many communities may also be the result of a long history of discrimination by our health care system.

Public health departments have been eagerly seeking innovative and evidence-based programs to improve their vaccine outreach efforts. Based on our survey results, we think a few strategies are particularly promising and worth scaling.

For instance, efforts to engage with community leaders and faith-based organizations, who have built trust with community members — are important to the success of the vaccine outreach effort. Food banks, schools, neighborhood organizations like YMCAs and senior centers are also important because they are established institutions that earned the confidence of those living in high-risk communities and neighborhoods. These institutions that many regularly visit can help with both promoting and distributing the vaccine.

Second, we must use clinics, pharmacies, hospitals, doctors and nurses to engage community members who are hesitant, or who may not know how to secure a vaccination appointment. Health professionals are among the most trusted sources of information about the COVID-19 vaccine. However, patients want to hear about the vaccine from their own health care provider — not just any doctor appearing on television or in social media. All providers need the tools, training and resources that will help them engage with their own patients — to promote vaccination and respond to common concerns about the vaccine. Additionally, clinics and hospitals, particularly those serving the hardest-hit communities, should be given the support and funding necessary to do large scale outreach to their patients.

Third, to reach more people in the community, we should turn to community-based vaccine navigators. Such navigators often come from the communities they serve and are trained to assist residents over the phone and in-person with creating and getting to vaccination appointments. Health care navigators have previously demonstrated that they can help people sign up for health insurance, find doctors and improve access care. Programs such as Get Out the Shot: Los Angeles, where trained volunteers help individuals figure out how to get vaccinated over the phone, are promising ways to reduce the digital vaccine divide and help some of the hardest to reach populations overcome barriers to vaccination.

Making vaccinations easy and available should continue to be a high priority, even as demand wanes in many communities. For the many residents in Los Angeles and across the country who are on the fence about vaccination, having ready access to a vaccine when they make the decision to get vaccinated is crucial. Innovative strategies such as mobile vaccine vans, which can bring the vaccine to residents who can’t travel, and pop-up vaccine sites that don’t require appointments may be expensive but are worth the investment. These low-tech solutions bring the vaccine several steps closer to people’s front doors, increasing the likelihood that they will take advantage of the opportunity.

We are on the cusp of ending this pandemic. Yet Gov. Gavin Newsom’s latest budget this spring fell $200 million short of what health care advocates said was needed to fund local public health agencies. That means to deliver the vaccine to some of the hardest-to-reach residents, we urgently need to support community-based organization, local leaders, health systems and volunteers. Ultimately, they are the ones who know how to get this job done.