Reporting on the unvaccinated: 'It’s complicated'

Kaiser Health News Montana correspondent Katheryn Houghton attended garage sales, wandered through historic neighborhoods, and chatted with people on their back porches to better understand their vaccine views.

One man she interviewed had questioned whether the pandemic was as bad as health officials claimed. He eventually decided to get vaccinated after consulting with a high school friend who had a science degree. His wife, though, felt the vaccines were too new and wanted to wait a little more. And their daughter was nervous because previous medical treatments had been hard on her body.

“With this one family only, you get to see this variety of issues,” she told participants in a Center for Health Journalism Covering Coronavirus webinar.

Houghton joined Amy Harmon of The New York Times and Alison Buttenheim, an associate professor of nursing and health policy at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, to discuss who is still unvaccinated and the complex reasons why. As U.S. vaccination rates plummet, speakers also discussed whether new incentives such as prizes and lotteries could help the country meet its vaccination goal.

Understanding the vaccine amenable

Despite $1 million lotteries and other monetary incentives, the United States is unlikely to meet its goal of 70% of American adults partially vaccinated by July 4, Harmon said. And while cases are on the decline overall, they are still high for unvaccinated individuals.

“We need to worry about this,” she said.

People are not getting vaccinated for a variety of reasons, ranging from mistrust and misinformation to political leanings. But Harmon wanted to focus on a category we hear less about, but one that is even more widespread than the so-called vaccine hesitant.

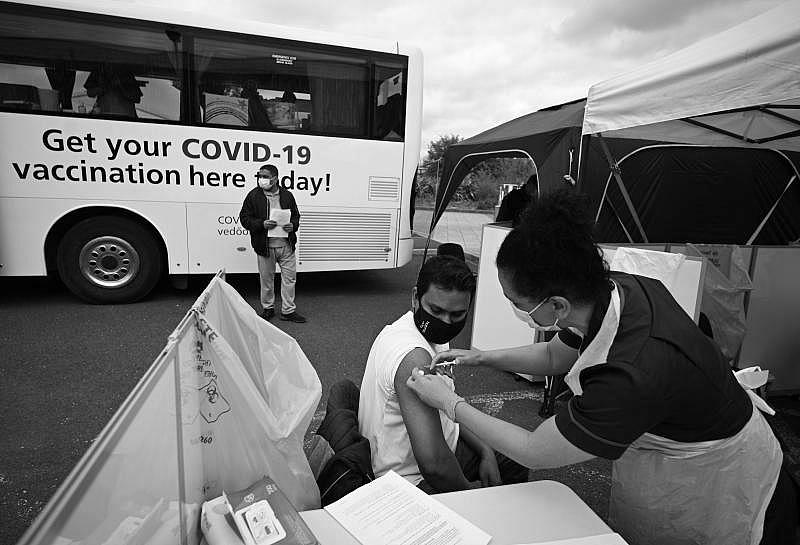

This group includes people who aren’t necessarily opposed to vaccination but still have access issues. They might have trouble taking time off work or worry about side effects causing missed workdays. Many would get the vaccine if it landed on their doorstep, such as the three dozen Austin grocery workers who got vaccinated when extra doses were offered in their store’s parking lot, she said.

Harmon also interviewed a man who just didn’t have enough time in his day as he struggled to take care of his household and work. Eventually, he got a vaccine at a local church when he happened to have a painting job there.

“It’s complicated”

The big takeaway of Montana journalist Houghton’s conversations about vaccines is “it’s complicated,” she said.

There’s a big variety of what vaccine hesitancy looks like, and often access issues overlap with personal concerns. With its vast rural spaces – rural populations are falling behind on vaccinations – Montana has been a great place to see these complicated decisions firsthand.

In one rural county, Houghton learned of the societal divisions already created with split votes on mask mandates and decisions on limiting crowds.

“COVID vaccines were another stage of this uncomfortable division they had dealt with as a community,” she said.

Even among Montana’s rural counties, the experiences were distinct, with varying levels of confidence in their local health systems and governments. All of this was complicated by the shared logistical challenges of getting the Pfizer vaccine shipped and stored.

With no perfect data on these often-overlapping issues, old fashioned reporting was the best option for understanding the nuances.

“You just have to actually talk to people on the ground,” Houghton said.

Will lotteries close the gap?

Buttenheim, who is part of the research team behind the Philadelphia lottery, is enthusiastic about the city’s approach.

Unlike some states that include only the vaccinated, Philadelphia will add all adults. If your name is picked, you’ll be asked whether you’re vaccinated. Those who answer no will be painfully aware of what they could have won.

“That anticipated regret…is very motivating, more motivating, than just ‘Ah, I’m not going to participate in the lottery,’” she said.

Before the rollout, Buttenheim had reservations about using financial incentives to encourage vaccination. She and other colleagues worried they could actually discourage vaccination, particularly among people worried about side effects. She also questioned whether lotteries were the best use of limited funds.

Flash forward to Philadelphia’s sweepstake, and her tune has changed. This is the right idea at the right time, she said.

In part, that’s a result of where we are in the vaccine rollout. With so many U.S. residents fully vaccinated, fears about the vaccine being novel or experimental are less potent. Another interesting part of the design: an emphasis on half of the prizes going to zip codes with the lowest vaccination rates.

Still, there are lingering questions among behavioral scientists as to whether these prizes and lotteries could crowd out someone’s intrinsic motivations. Will the same efforts need to be repeated if boosters are required?

Since human beings are social creatures, some of the most persuasive messaging might simply be the awareness of how many of your peers have been vaccinated, Buttenheim said: “Once you realize 70% or 80% have, that tends to be pretty persuasive.”