Will the pandemic worsen educational outcomes for Pittsburgh’s Black children?

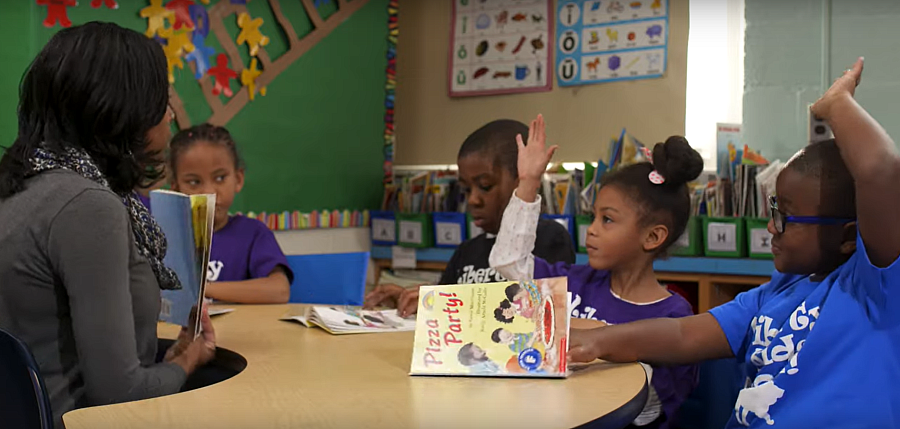

(HimmelrichPR via Creative Commons)

To be a Black student in Pittsburgh Public Schools means the odds are stacked against you. And they have been for more than 30 years.

In 1992, the crisis reached a boiling point with five parents of Black students filing a complaint against the district with the state’s human relations commission. In the complaint, the parents said the district discriminated against Black students by disciplining Black students at a higher rate and giving them lower grades than white students.

Nearly 30 years later, the disparities persist. There have been numerous plans, programs and efforts aimed at curbing the gaps, to no avail. Recent data shows Pittsburgh’s Black students are still more likely to be criminalized and experience poor educational outcomes. An October 2020 report by the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission described the district’s achievement gaps in student performance as “stubbornly high.”

The community has long wanted better educational outcomes for Pittsburgh Public Schools; COVID-19 has only amplified the call. Black and brown communities have been disproportionately impacted by the virus and are weathering the worst of the pandemic impacts.

Two Pittsburgh city councilmen declared a state of emergency in the city’s public schools in February 2021, citing dueling public health crises in the school system — COVID-19 and systemic racism.

Poor outcomes have spanned across numerous administrative cabinets, school boards and despite multiple strategic plans to eradicate disparities. Still, Black Pittsburgh students are more at risk of performing poorly compared to peers or being criminalized. Why?

Why haven't legislators or the state Department of Education stepped in with more oversight or enforcement action? What has been the impact of such sustained poor outcomes? What practices have other districts used to narrow achievement gaps and better educational outcomes?

When schools were shuttered last year and districts needed to leap into action to shift to virtual environments and address new student needs, it was just the latest blow for the city’s school district.

When Pittsburgh students convene in the fall for in-person learning, it’s estimated they’ll have lost nearly two years of learning. Students will return in the fall as different people with new needs.

The district now faces another set of hurdles as it looks for ways to address increased needs, recover from learning loss and work to close decades-old gaps as new ones develop.

Some community members have proposed new solutions for local education. There are no easy answers.

Though little to no progress has been made on these persistent problems, the district has increased spending. From 2017 to 2019, average per-pupil spending in the district rose 10%, from $24,433 to $26,909. The district went from a $65.9 million surplus in 2015 to a $39.4 million deficit in 2021. Pennsylvania schools’ spending per pupil surpasses the national average of $14,000.

With millions of dollars spent each year by a district whose budget eclipses the city budget, some wonder about the return on investment for taxpayers and the city’s Black residents.

For the 2021 National Fellowship, I will illustrate how educational outcomes are evolving for Pittsburgh students in the pandemic and amid the district’s historic struggle to narrow its achievement gaps. I will also examine the work at other school districts nationwide that have managed to close achievement gaps between Black and white students to see what lessons could be applied locally. I plan to use a collection of district data, including forthcoming testing and enrollment data, and state education data.

My storytelling won’t stop at data. I plan to lean on interviews with current students and alumni, who will discuss the impacts and consequences of an inequitable education, as well as those now working to be part of system-wide change for future Pittsburgh kids. I will interview deeply invested community members, current and former educators, advocacy groups and experts to create a timeline of attempts to narrow the gaps and bubbling community plans to solve the educational crisis.

Our hope is that the project becomes the most comprehensive journalistic look to date at why Pittsburgh Public fails its Black students.