Why is this ancient disease ravaging California communities?

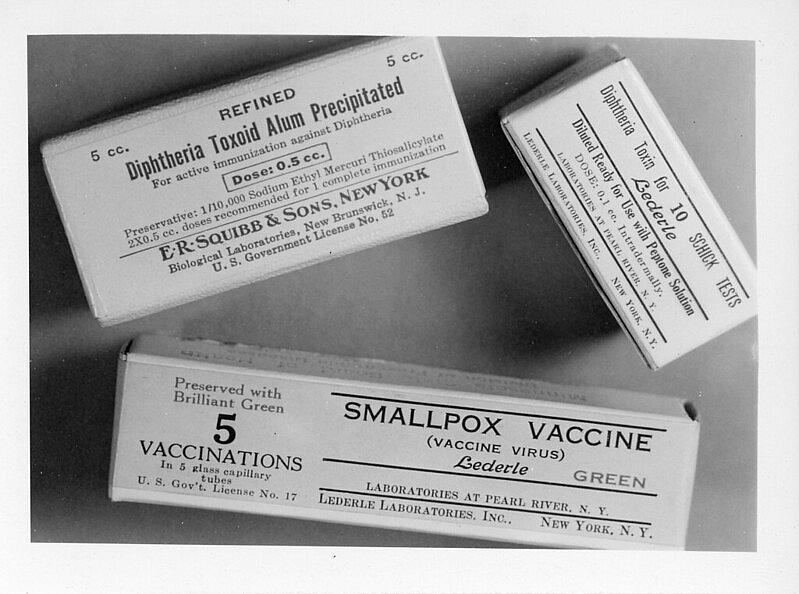

(Photo by City of Minneapolis Archives via Flickr/Creative Commons)

Thirty years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was ready to declare syphilis a dead disease. The cure was simple: Penicillin. We had defeated smallpox in 1949. The elimination of syphilis felt like an inevitable medical success. But in 2014, Fresno County issued a health alert for maternal syphilis and congenital syphilis. The county’s numbers were exploding from 0 cases to 100 to 200, doubling each year.

Health officials didn’t quite know what to make of this so-called dead disease. “At that point most (physicians) had never seen syphilis and definitely not congenital syphilis,” says Jennifer Wagman, a researcher from UC Los Angeles who conducted a syphilis study in neighboring Kern County in 2015.

In the past seven years, California has witnessed a staggering increase in maternal and congenital syphilis cases. Nearly 450 babies were born with the infection in 2019 — a number not seen in the state since 1993 and 13 times more infections than a decade ago. That year, 43 stillbirths and infant deaths were caused by the disease.

These deaths were entirely preventable.

Syphilis is easily treatable with antibiotics, but the most at-risk mothers often have no access to doctors, struggle with substance abuse and housing instability, and are wary of the stigma that surrounds the disease. Left untreated, syphilis causes severe neurological disorders, organ damage and infant death. Black and Latina mothers and babies have suffered the most.

Local and state public health officials are desperate to find and treat these mothers and babies, but years of dwindling funding have shuttered clinics and shrunk sexually transmitted disease teams. Most mothers who lack prenatal care don’t even know they’re infected until they give birth.

There are myriad reasons why historical diseases are reemerging, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made things worse by stymying health officials’ ability to devote resources to sexually transmitted disease prevention. Public health officials suspect that many infections have gone undiagnosed and untreated as fewer people sought health care of all kinds.

As a 2022 California Fellow, I intend to use state data from the STD Control Branch to explore how this issue intersects with historic failures to provide adequate housing, drug and mental health interventions, public health funding and basic health care across the state.

It is also important that this story illuminate the challenges many women face when trying to access basic prenatal care. Many have to travel hours to get to a clinic or fear that their children will be taken away from them because living conditions have rendered them homeless or addicted to drugs. The data outlining the issue is faceless, but the victims are not.

I hope that my reporting will give a face to these women and children and impact policymakers who have the power to enact real change.