Treating long-term war trauma for Cambodian genocide survivors

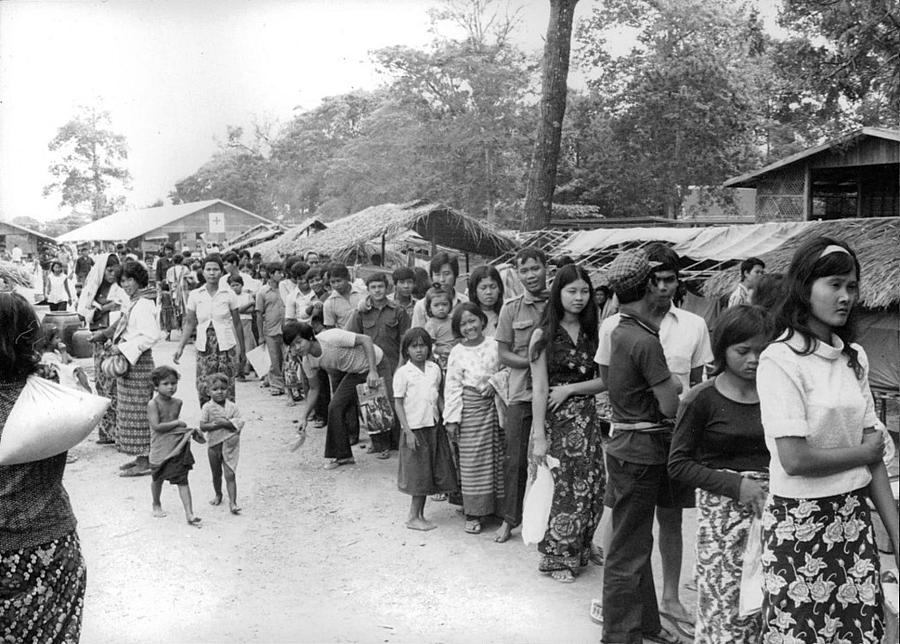

Cambodian refugees.

(Photo via Soreath Hok)

Growing up as a Cambodian American in a family of refugees can often feel isolating. There are so many cultural identities to juggle at home, work and school. Among my peers, there were very few people who could relate to my history and experiences. Like all Cambodians, I grew up hearing the stories about the war and genocide from my parents and grandparents.

Between 1975-1979, two million Cambodians were systematically killed by the Khmer Rouge, led by Pol Pot. Survivor stories detailed horrific atrocities. Many endured starvation and witnessed the murders of their family and friends. Although terrifying, my family’s stories always ended with a note of hope because they always reminded me that they did survive. We arrived in California in the mid-1980’s as part of a large wave of Cambodian refugees. Making a new life in the U.S. allowed for a fresh start for my family, who never spoke extensively about their experiences. As a result, I never truly understood the deep trauma they lived with.

It wasn’t until five years ago, when I started working as a Cambodian interpreter that I saw a different side to the impact of the war. I was called to service government institutions, attending medical and social service appointments. I met Cambodians of different ages and backgrounds, who all had the same thing in common: the trauma of war still haunted them. At these appointments, I found that the symptoms of PTSD had manifested into long-term physical, mental and emotional damage, even decades after the dissolution of the Khmer Rouge regime.

My first social service appointment was interpreting for an intergenerational Cambodian family. Child Protective Services was interviewing the grandmother about her husband, who often woke up in the middle of the night from nightmares about the war. CPS was concerned that he slept with a gun near his bed, in a household with his young grandchildren. His family said it made him feel safe from his constant nightmares. One night, police were called to restrain the grandfather who refused to put down his loaded weapon. It ended in his arrest and an overnight stay in jail, yet another traumatic event for an elderly man who couldn’t speak English or fully understand what was happening to him. It was just one example of the long-term effects of war trauma on this community. Years after my experience as an interpreter, these stories stayed with me.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are 340,000 Cambodians and a third of them, about 120,000 live in California. According to a RAND study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Cambodians are one of the largest refugee groups in the U.S. But 40 years after resettlement, this community is still grappling with mental health issues. The study revealed high rates of PTSD (62%) and depression (51%) among participants. According to the study authors, “the pervasiveness of these disorders raises questions about the adequacy of existing mental health resources in this community.”

The study found that four percent of the Cambodian refugees studied had alcohol or drug problems, had incomes below the poverty level, little education and low English language skills. It also found 72% received government assistance. Since the study was last done between 2003-2005, what has changed? As part of my 2022 California Fellowship project, I want to explore the barriers that still exist to seeking service and identify treatment methods that have effectively helped this community deal with trauma. After 40 years in a new country, how has the impact of war trauma in older generations affected younger generations? The trauma that the elders experienced gets passed intergenerationally. How does this younger generation cope with that trauma and do treatment methods differ from the older generation of genocide survivors? For those who do seek treatment, what do those programs look like? I want this reporting project to better inform the Cambodian community of mental health treatment options and reduce the stigma around seeking help.

I’ve identified three California communities that have shaped programs over time to serve Cambodian refugees in Oakland, Long Beach and Fresno. These programs have been developed with a unique understanding of mental wellness needs of Cambodian refugees. In this way, I can combine my own lived experience and the resources of the USC Annenberg California Fellowship to shed light on a topic and a community that has historically received little coverage. Through the personal stories of survivors and program staff, I want to find commonalities that may have emerged to provide mental health treatment to a growing, but underserved population.

On a deeper level, I want this reporting project to bring awareness to the fact that this community still suffers from a dark period in history, with intergenerational implications decades after the brutal atrocities of the Khmer Rouge regime. I think it has the potential to illustrate a larger picture of the lasting effects of war trauma as we look to current events in Ukraine and Afghanistan.