Examining local universal care: How San Francisco took an independent — and expensive — approach to covering the uninsured

In 2007, San Francisco embarked on a rare and bold experiment, resolving to provide universal health care to its residents. The premise was simple - take an existing local safety-net system of clinics and hospitals and transform it by tracking all patients in one database and giving each patient a medical "home." The approach, aspects of which are being rolled out in communities across the country, promises to reduce cost, increase quality of care and expand the number of uninsured people covered.

Four years later, many of the goals of the program, Healthy San Francisco, have been met. Over time, more than 100,000 previously uninsured people have been covered. The current enrollment of 54,000 people is anywhere between half and three-quarters of the estimated uninsured population in the city.

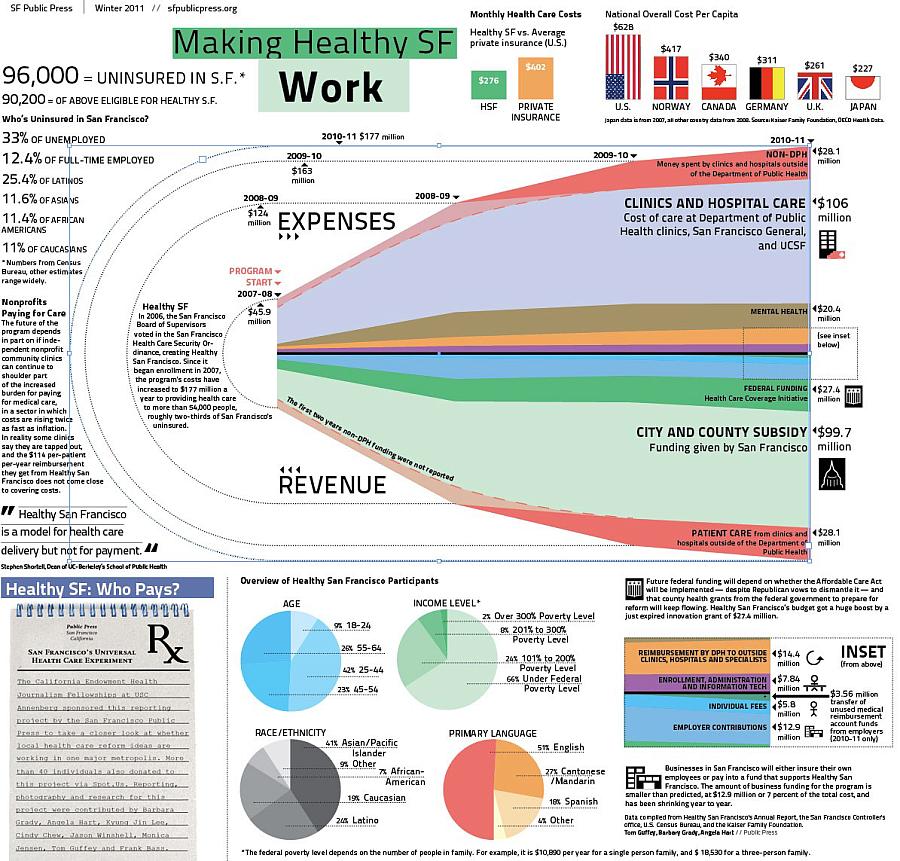

But to do so, the city's Department of Public Health has dug deep into its general fund at a time when most of the other departments in the city have had to cut back. And it has earned less than expected from other sources - payments from low-income patients and a newly created business fee. A $27 million federal government grant expired in July, so the city will have to look for alternative funding sources. The city's baseline safety net expenditures of about $100 million annually have been wrapped into the $177 million budgeted for the program, and with medical costs rising every year, that liability is expected to continue to grow much faster than inflation.

The big question confronting this ambitious program: can it be sustained financially?

Patient medical records are still kept on paper at the Chinatown Public Health Clinic. Photo by Jason Winshell/SF Public Press

(Left: Patient medical records are still kept on paper at the Chinatown Public Health Clinic. Photo by Jason Winshell/SF Public Press)

The San Francisco Public Press, which covers public policy in the city and across the region on its website and in a quarterly broadsheet newspaper, decided to go in depth to address this fundamental problem. Coverage of this massive health care program has been nearly absent from the mainstream media outlets. The most in-depth piece about the program was a story in San Francisco Magazine more than a year ago, discussing mostly the program's promise, before it had much of a track record. Recent coverage in the two daily papers, two weeklies and broadcast media focused almost entirely on a current controversy about health fees levied on businesses, but not on the macroeconomic picture of the program.

With a USC Annenberg/California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowship starting last spring, we were able to focus on Healthy San Francisco's financial sustainability. The rising cost of health care has dominated headlines for years and is one of the key points of political contention between the major parties in Washington. We wanted to examine up close a promising local initiative that could, perhaps, inform the national discussion and trim some of the billions wasted in the current medical care business model. We also wanted to explore what its services have meant to the health of city residents.

Patients vox by SF Public Press

The resulting project: "Healthy San Francisco: Who Pays?" was a special four-page section in the Winter 2011 edition of the print newspaper. Three reporters, two photographers and a graphic designer contributed to the research, interviewing the director of the program, clinic directors, technology specialists, medical staff, independent experts and dozens of patients. They visited nearly a third of the medical clinics and hospitals in the Healthy San Francisco network and discovered some compelling trends:

-While the program has succeeded at providing something like health insurance to tens of thousands of people who never had access to that level of care, without taking into account pre-existing conditions, most of the patients are poor - below 200 percent of the official poverty level. As a result their contributions are millions of dollars below the planners' initial projections.

-The requirement that medium-size and large businesses pay for the program by giving some level of coverage to their employees, including an option for medical savings accounts and direct contributions to Healthy San Francisco, the program has brought in less money than projected.

-Some businesses are exploiting a loophole in the law to drain unused funds at the end of the year. And there is evidence that some businesses, after initially complying with the law, are lately dropping private insurance in favor of reimbursement plans that are much cheaper. They also leave patients not fully insured.

-Healthy San Francisco appears to be a big bargain, with the average cost of care calculated at $276 per person per month. That compares with an average of $402 for private insurance. But the accounting does not include millions of dollars that clinics and hospitals have had to absorb to care for the additional patient load and technology upgrades to make the system function efficiently.

-Federal grants to spur innovation in health care helped get the program off the ground but may not be renewed, especially if political winds change direction. And while the program was intended to be a bridge to national reform efforts, those programs now face challenges in Congress and the courts.

We published the stories in the print edition Nov. 16, and online later in the week. The response has been very encouraging. In the following weeks the series of four articles has received several thousand hits on the website and has contributed to a marked uptick in purchases of the newspaper, which sells for $1 at about 50 retail locations. The story has been Facebooked, tweeted and retweeted more than 1,000 times. Copies were dropped off at the offices of every city supervisor, the mayor and the Department of Public Health, where we have yet to receive an official response.

We have, however gotten ideas for follow-up stories through social media. The point of this project was not to produce a package of stories in one lump and then move on. The reporters all say that they have deepened their understanding of health reporting and want to do more. Their laboratory will be follow-up stories on this program and its evolution over time through the Public Press. We are hoping to engage user of the program especially however they can best interact with journalists - online and offline.

Also our lead reporter, Barbara Grady, got a cache of documents from the city indicating which companies had reduced their private insurance offerings. We plan to do follow-up articles on this, as well new reporting by Angela Hart on new budget information - public records that clinic directors should have shared with us months ago. We expect to find several million dollars in extra cost for technology that is not part of the official $177 million tally for the program.

We are planning a live event in in January in collaboration with the Bay Area chapter of the Association of Health Care Journalists to get responses from patients, doctors and the general public to our stories and get ideas for follow-up coverage. Reporter Kyung Jin Lee is developing a produced audio story for public broadcasting that uses the extensive recordings we did with a wide variety of sources.

The fellowship was helpful to us in three concrete ways.

First, senior fellow Frank Bass helped us break down the demographics of San Francisco by studying recent U.S. Census data. This helped not only this project but also other reporting on a wide array of stories, indicating neighborhood by neighborhood information on where we would expect to find health problems on a local level. The data show income levels by census tract. Even though one survey asks health insurance status, this information is not asked frequently enough for us to get meaningful neighborhood statistics.

Second, the fellowship helped us moderate the ambition of our project, which still took six months to assemble. We couldn't report on the quality of care for any of the thousands of medical conditions treated through the system. We were also planning to spend a few weeks hanging out at the San Francisco General Hospital emergency room to observe and interview uninsured patients as they were admitted for non-emergency conditions. It is Healthy San Francisco's contention that the program has significantly reduced emergency room visits by catching problems earlier and diverting them to clinics, saving money. Healthy San Francisco has produced numbers to suggest that these savings are significant, but the statistics are difficult to interpret because individual health cannot be tracked if tens of thousands of people enroll and disenroll every year.

Third, it helped us focus. Finance remained our main concern - the potential savings notwithstanding, in part because of the unique nature of San Francisco's foray into health coverage. There are a number of localities - states, cities and counties - rolling out their own universal care programs. Massachusetts and Vermont have the most ambitious, but San Francisco's approach of tweaking an already robust safety-net clinic system makes it the first major American city to take this route.

Third, the $2,000 stipend that came with the fellowship allowed us to pay decent freelance fees to experienced journalists who could afford to spend the time to do significant shoe leather reporting. We supplemented this with $537 in extra donations earned through a pitch to readers through the online journalism micro-funding website Spot.Us. We hope that our careful but high-impact local reporting on a complex issue, supported by the USC Annenberg California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships, will pave the way for future funding from foundations and individuals for similar projects and even an ongoing health care beat.

See the entire package of stories:

-San Francisco's universal health plan reaches tens of thousands, but rests on unstable funding, by Barbara Grady

-Some employers drop private health plans for San Francisco's subsidized public option, by Barbara Grady

-Participants appreciate safety-net health access program, but note gaps, by Kyung Jin Lee

-Medical records supporting San Francisco's universal care add millions to official cost, by Angela Hart

-And see also the full-page graphic by designer Tom Guffey

* * *

P.S. Like all the participants in my cohort of the Health Journalism Fellowships, the San Francisco Public Press is part of an explosion of startup experimental local news organizations attempting to address shortfalls in serious news coverage as news organizations across the country cut back. The Public Press is nonprofit and noncommercial. We do not accept advertising. We relying on foundation grants (such as The California Endowment's), syndication, micro-funding, newspaper sales ($1 retail) and the generous support of hundreds of individuals who have donated through our membership program, which is based on the public broadcasting pledge model. Basic memberships start at $35 a year, which entitles you to mailed copies of the newspaper for a year and discounted or free entry to events. Send us $50 and you also get a vermillion SF Public Press branded T-shirt. We are doing a shameless pledge drive because it is necessary to support independent, professional local reporting on topics not covered by the mainstream press. If you're moved to help out, contribute - ideally by Dec. 31 - to our year-end fund drive!