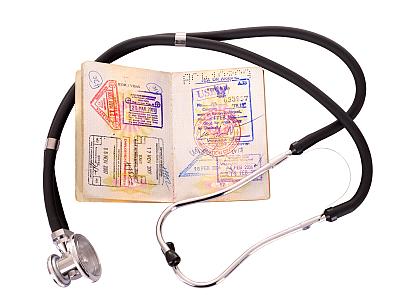

Q&A with Leigh Turner: Tracking Medical Tourism Consequences

When I first asked Leigh Turner if he would consider doing an interview with Antidote, he was a well-published but not particularly well-known associate professor of bioethics at the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics.

When I first asked Leigh Turner if he would consider doing an interview with Antidote, he was a well-published but not particularly well-known associate professor of bioethics at the University of Minnesota's Center for Bioethics.

He agreed, but before I wrote up my questions, he was transformed into a national example of academic freedom in action. Turner has had a longstanding academic interest in patients traveling internationally to seek treatments that may be unavailable or, at worst, illegal in their home countries.

He had written a letter to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration asking it to investigate the stem cell company Celltex Therapeutics for its role in distributing stem cells used by doctors in unproven and potentially dangerous therapies. The company responded by sending a threatening letter to the University of Minnesota asking it to disavow Turner and force him to retract the letter.

Academics everywhere responded with alarm, and journalists everywhere wrote about the controversy. I finally did send Turner some questions, and he responded in great detail about his work, his mission as an ethicist, and his ongoing concern for patients who are the targets of stem cell marketing. The first part of our interview is below. It has been edited for space and clarity.

Q: In 2007, you wrote a great journal article about medical tourism that covered a wide range of treatments being offered in low-income countries to high-income patients. You touched on stem cells just once. When did stem cell tourism start to capture your interest and why?

A: I had a lot of fun researching and writing that article. It was like putting together a puzzle without knowing in advance what image would appear once the pieces were assembled. I know everyone (including me) uses the phrase "stem cell tourism" but it is important to remember that these trips are hardly holidays and some of them end with the death of stem cell recipients.

A: I had a lot of fun researching and writing that article. It was like putting together a puzzle without knowing in advance what image would appear once the pieces were assembled. I know everyone (including me) uses the phrase "stem cell tourism" but it is important to remember that these trips are hardly holidays and some of them end with the death of stem cell recipients.

I collected material on the topic as I wrote my first article about medical travel and then became more interested as the volume and quality of research addressing this topic increased. Individuals with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, and many other illnesses travel for stem cell procedures provided at clinics in China, Dominican Republic, India, Mexico, Panama, Thailand, Ukraine, and elsewhere.

Patients pay tens of thousands of dollars for so-called stem cell "treatments" that have not been demonstrated to be safe and effective. The practical result is that some individuals pay for such procedures and self-report that their health status is improved, other patients are harmed as a result of receiving unproven stem cell interventions, and some patients die.

I regard this phenomenon as a sign that while there is a global marketplace for medical care, it is a poorly regulated bazaar in which vulnerable, often desperate patients are at risk of exposure to scam artists and hucksters.

Let me be clear: there are many reputable international clinicians and health care facilities that offer affordable and high-quality health care. I'm not trying to advocate a xenophobic attitude toward health care in other countries. But it is important to understand just how poorly stem cell clinics are regulated in many of the countries that attract international patients seeking cures or treatment for diseases that are currently untreatable.

Q: There's a tendency among U.S. journalists – and I have fallen prey to this too – to assume that U.S. health care offers the best money can buy while other countries – even countries with excellent medical training and the latest technology – offer substandard or unethical care. It's often enough to say in a story that someone underwent a surgery "in the Philippines," for example to signal to readers that the medicine was sketchy. Is that really fair, though, and should the ethical issues surrounding health care ignore national boundaries?

A: My immediate reaction is to state that U.S health care offers the most expensive treatment money can buy. One of the great dangers when writing about patients going abroad for health care is to provide an account that uses cultural stereotypes and unsubstantiated claims about quality of care in particular settings. It is all too easy to craft a narrative that emphasizes dirty clinics, outdated equipment, and unqualified clinicians in other countries while ignoring the many patients who have been harmed or died after receiving medically negligent care at health care facilities in the United States.

I recently published an article about patients who died after undergoing cosmetic surgery or bariatric surgery outside their home country. One case involved Kathleen Cregan, a woman from Ireland, who died after having cosmetic surgery performed by a doctor in Manhattan. Before she died, this physician had settled 33 medical malpractice lawsuits. I'm unable to understand how a doctor with such a record retained his medical license and was allowed to continue performing surgery. Ms. Cregan's death reminds me that it is important to be critical of medically negligent health care at hospitals and clinics around the world while realizing that this same critique needs to be applied to domestic physicians and health care facilities that cause avoidable harm to patients.

I'll add a personal remark. I'm Canadian. I live and work in the United States at present, but I suspect that I'm like many Canadians when I think about health care in the U.S. I see a country that pays far more for health care than any other nation, has approximately 49 million uninsured residents, has profound socioeconomic inequalities and health inequities, and spends a great deal of money building and running prisons rather than finding ways to build stronger safety nets and protect its citizens from falling into medical debt and health-related bankruptcy. This last issue is why some Americans go abroad for care. They aren't traveling to India or Mexico for a holiday. They go abroad for medical care because they have no health insurance and they can't afford to pay the rates that U.S. hospitals charge uninsured patients.

Q: You have called stem cell medicine "21st Century quackery". Isn't that a little over the top? Aren't stem cells one of the most promising areas of medicine, like genetics and nanotechnology?

A: I support carefully designed and conducted studies in these areas and definitely do not regard legitimate medical research as "quackery". It is possible that all three of those areas will, in time, lead to important new therapies. If new treatments emerge, it is important that they are based upon carefully designed studies that have appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria, test for safety and efficacy, and in all other respects meet standards for ethical, scientific, and legal clinical research. Conducting such studies takes time, and along the way there will be many failures-though of course much can be learned from studies that do not lead to desired outcomes.

What concerns me are all the clinics that use patient testimonials and other promotional devices to market stem cell treatments and charge tens of thousands of dollars for so-called stem cell "therapies" for which there is no evidence of safety and efficacy. That's the "quack" or "scam" side of health care that I find worrisome. While reputable, credible research is underway, clinics in the U.S., China, India, Mexico, and elsewhere make unfounded claims about stem cell "treatments" and "cures".

Their marketing messages are directed at individuals who have serious medical problems, are desperate for a cure, and often have nowhere near the personal wealth needed to be able to afford procedures. These hustlers make a lot of money by taking the hope and desperation of ill individuals and emptying their pockets while putting them at serious risk of harm. We need to remember the scam artists every time someone makes an argument claiming that the FDA, state medical boards, and other bodies concerned with protecting vulnerable individuals from harm have no business interfering with the doctor-patient relationship and the practice of medicine.

Q: You recently paraphrased Jan Helge Solbakk at the University of Oslo, saying that "bioethics has moved from social and ethical critique to corporate lackey." Looking back at the last five or 10 years, what would you cite as the strongest evidence for this? And aren't there just as many examples of ethicists challenging business practices?

A: You make a fair observation; there are numerous examples of bioethicists challenging various corporate practices. Acknowledging this point, there are many ways in which bioethicists in the U.S. and other countries have problematic ties to the corporate sector. Crudely lumping together consulting gigs, appointments to advisory boards, funding provided to bioethics centers, research grants to individual ethicists, and other sources of corporate funding, bioethicists have financial connections to a long list of companies.

This list, much of which I draw from publications by Carl Elliott, includes but is not limited to: Advanced Cell Technology, Celera Genomics, Geron Corporation, Johnson and Johnson, Eli Lilly, Merck Company Foundation, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Hoffman-La Roche, Sun Life, Monsanto, Astra-Zeneca, Schering-plough Corporation, Aventi Pharmaceuticals Foundation, Medtronic, DNA Sciences, Human Genome Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck-Frost, deCODE Genetics, E. I. du Point de Nemours and Company, and Millennium Pharmaceuticals.

This list does not include the names of companies that operate for-profit institutional review boards and have bioethicists as employees or consultants. I should add that it is prepared without the aid of a database-such as the Dollars for Docs database provided by ProPublica-that can be used to search for all bioethicists with ties to the corporate sector.

While many bioethicists work at hospitals, universities, think tanks, and other organizations and have no direct connections to industry funding, over the last decade numerous bioethicists have established significant financial ties to pharmaceutical companies, biotechnology firms, and medical device companies. One problem with such funding is the risk that the people paying the piper call the tune. Another problem is that many bioethicists address ethical issues directly related to corporate practices.

By accepting funding from the companies they purport to investigate there is risk that bioethicists will call into question the independence and integrity of their field. It would not be a good thing if bioethicists come to be seen as hired guns working for their private sector funders. Disclosure of financial conflicts-of-interest is one common way of attempting to address this problem. However, disclosure simply announces the existence of conflicts. The conflicts themselves remain.

There also is the more narrowly focused matter of accepting employment at particular corporations. I doubt that discussing "the private sector" as though all companies are morally equivalent is particularly helpful. It seems to me that we should have a different response to a bioethicist who decides to go to work for, say, a pumpkin patch and roadside vegetable stand, and a bioethicist who accepts employment at a company marketing clinically unproven stem cell infusions. I mention this point because I see Glenn McGee's move to Celltex Therapeutics as the most morally problematic connection that I've ever observed between a bioethicist and a corporation.

Next: Separating academic politics from ethical violations

Related Posts:

Slap: Celltex Threatens University of Minnesota For Ethicist's FDA Letter

Q&A with Leigh Turner, Part 2: Finding Ethical Quandaries Amid Academic Rivalries

Q&A with Leigh Turner, Part 3: Celltex Tries to Intimidate a Whistleblower