The following excerpt is from a new short e-book by Mona Gable called “Blood Brother: The gene that rocked my family,” which tells the story of her brother’s battle with Huntington’s and the outcome of her own decision to get tested.

One late winter morning in 2011, I sat in the waiting room at UCLA’s pediatrics clinic. Although I have children, I wasn’t there because of them. I was there to see if I was going to die anytime soon. After three weeks of agony, I was about to get the results of my genetic test for Huntington’s disease.

Oddly, as I sat in the room with its cheerful murals of Disney characters, my husband and a gaggle of parents and toddlers around me, I was more numb than afraid. I suspect I was still in shock. I was also still grieving my youngest brother’s death.

Until a few months before, I had been only vaguely aware of Huntington’s. I knew it was the fatal brain disorder that had killed iconic American folksinger Woody Guthrie. But I didn’t know it was rare. I didn’t know it was purely genetic, passed down from parent to child. And I didn’t know it combined the worst aspects of Alzheimer’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and Parkinson’s—a cocktail of misery and eventual death. Or that there weren’t any treatments or a cure.

And then in December of 2010, my brother Jim was diagnosed with Huntington’s—on top of terminal colon cancer—and suddenly I was thrust into a world I never could have imagined. Jim didn’t last long; he died of cancer on Christmas Eve, only 58. Because we were close, so much alike, it was like watching myself die, too.

For years I had watched Jim’s demise from Huntington’s, his withering away, not realizing what was wrong with him. At times he couldn’t control his body and looked like he was drunk. He fell a lot and had frequent car accidents. When we talked on the phone, I often had to ask him to repeat himself because his speech was slurred. Since we were kids, he had always been sweet and good-natured. But as he moved into his 40s he was quick to get angry. Just as strange, my liberal California brother had turned into a hard-core conservative, a supporter of George W. Bush and a climate change denier. Part of this I wrote off to his living in Colorado Springs, a hotbed of American evangelism. Yet, his symptoms haunted me.

Mostly, I thought the changes were the result of a brain injury from a bad snowboarding accident. Several years before, he’d fallen off a ski lift and the chair had struck him in the back of the head. For a while he’d had seizures, even though he’d been wearing a helmet when injured. Epilepsy had killed my mother, upended her life almost since I was born, so the reality that Jim now had epilepsy seemed especially unfair.

Because I lived in Los Angeles, I usually saw him only about twice a year, so I didn’t grasp how sick he was. Whenever I’d ask about his health, if he’d seen his neurologist, he’d insist he was “fine.” He had a little movement problem, something called “dancing body syndrome.” He was taking medication for it. He could still practice dentistry. But I was skeptical. How could he insert a crown if he couldn’t stay still?

If only I’d pursued my suspicions. Maybe then Jim wouldn’t have been able to live in such denial. He could have gotten the care he needed and not suffered as much. Maybe his colon cancer also could have been diagnosed earlier. At the very least, Jim’s depression could have been treated. Maybe he wouldn’t have had to helplessly watch as his practice collapsed and his financial troubles mounted. Maybe he and my sister-in-law would have felt less ashamed, less alone. Maybe he wouldn’t have had to pretend to be so brave, for his kids and for our two siblings and me.

But I didn’t pursue it. I wanted to respect his dignity. In our highly competitive family, Jim had often confided in me that he felt he wasn’t good enough, successful enough. I understood. As a young woman who craved adventure and, as a writer who didn’t always have a real job and didn’t marry until age 36, I often felt different, too. I wish I’d been more assertive with him about his health, dragged him to the doctor myself. When we were little, he had taken care of me, allowed me to tag along when he walked through the canyon to school, rode bikes with his friends, or went bodysurfing in the churning waves. He didn’t leave me behind. I still feel anguished that I didn’t do more.

He never complained. The last time I saw him before the revelation of the Huntington’s secret that would rock our lives was in early 2010. Jim had come to Los Angeles for a dental convention. Usually he stayed with his college friends or at a hotel, but this time he asked if he could spend the night with us. His wife was not with him. I hadn’t seen or talked to her in nearly two years. At the last family reunion in Colorado in 2008, they’d had a fight. Overnight, she and the kids had disappeared and gone home. Afterward, I had written her a letter, telling her how sorry I was about their problems, Jim’s declining health. Call me if you need to, I wrote. I never heard from her.

When I called Jim’s house, I always got the answering machine. Most of the time it was full. It was like trying to communicate with ghosts.

The night he stayed with us in L.A., we took him to dinner at Casa Bianca, our famous neighborhood pizza parlor. For some reason I saved the receipt. I keep it in a desk drawer in my office, and every so often I take it out and look at it, remembering. It was a fun night. We laughed, drank the strong house red wine, and polished off a large pepperoni pizza. Still, I also remember anxiously watching him. He was wobbly, unsteady, and he had lost a lot of weight. His jeans were hanging off him like a shroud. When I asked him about it, he said he’d been running again. People with Huntington’s, I now know, have a metabolic disorder that causes them to burn up calories faster than they can consume them. It’s a battle to not starve.

“Good night, Jim,” I said, kissing him.

“Thanks for letting me stay,” he said, sweetly.

The next morning I dropped him off in front of the Wilshire Grand on Fifth Street downtown. I hugged him and watched with tears in my eyes as he walked up the stairs into the lobby, his garment bag flying like a kite. That’s when I noticed the doorman. He had turned around and was staring at Jim as he danced up the stairs. I felt my cheeks starting to burn. I wanted to go over and shake him.

Stop staring! Don’t you see? He can’t help it.

When I look back, I see so much. I should have known that dancing body syndrome was code for the movement disorder in Huntington’s. I frequently wrote about medicine, about AIDS, cancer, advances in heart and liver transplants. I could have easily looked it up. But I wanted so badly to believe that Jim was OK. And maybe I didn’t want to know?

By the time I saw him 11 months later, in November of 2010, he was emaciated, his six-foot frame sickly yellow skin draped over bone. I had to stop myself from screaming. Instead, I leaned over and kissed his check. “Hi, honey,” I said. “I’m here.” He looked up at me, his hazel eyes moist, and grinned.

At that moment I had no idea Jim had Huntington’s. He had actually been admitted to the hospital with severe abdominal pain, which turned out to be advanced colon cancer. But for years, as his behavior and health deteriorated, my sister-in-law suspected he might have the horrific brain disorder. She just never told anyone.

One afternoon as we sat in the gray autumn light of the hospital chapel, the dark Rockies looming outside, she started crying and confessed: A few days before, she’d had my brother secretly tested for Huntington’s. He was positive. Yet when the doctor tried to give her Jim’s results after confirming his diagnosis, she didn’t want to hear the two key numbers that revealed the severity of his disease and walked away. Just as I was trying to absorb this, she said she didn’t want Jim to know, either. What good would it do to know he had Huntington’s? The colon cancer was bad enough.

There was more. As I was soon to learn in my frantic research, each child of a parent with the disease has a 50 percent chance of getting the deadly gene. And if you inherit the gene, you eventually die.

Suddenly, I felt as if I’d been plunged into an Alice in Wonderland reality, where nothing made any sense. I didn’t know enough yet to be afraid for myself, for my children. But as I sat there hugging and consoling my sister-in-law, I felt a rising sense of dread. Part of me had the urge to yell at her. Why had she and Jim never confronted this? And what was I to do now with the terrible information she had just unloaded on me?

It was only later I was able to appreciate that my sister-in-law had told me at all. If she hadn’t, I would never have called Jim’s doctor and begged him to disclose my brother’s test results. I never would have known that my children and I faced a possible death sentence.

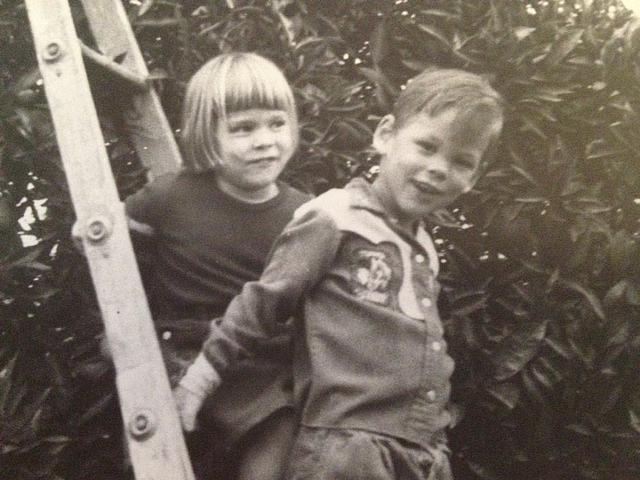

Photo courtesy of Mona Gable.