4 key things to know about USA TODAY’s investigation into nursing home failures during COVID-19

This story was originally published in USA Today with support from our 2021 National Fellowship.

Deaths across a scattering of Midwestern nursing homes began surging around Thanksgiving. By Valentine’s Day last winter, the death toll had climbed into the hundreds.

A USA TODAY investigation has traced the casualties back to one nursing home chain, Trilogy Health Services, owned by a real estate venture with a new business plan for the cutthroat world of eldercare.

THE INVESTIGATION: This nursing home chain stood out for nationally high death rates as pandemic peaked

Residents at Trilogy’s 115 campuses died of COVID-19 last winter at twice the national average for nursing homes, USA TODAY found, based on figures facilities must file weekly with the federal government. Presented with USA TODAY’s findings, the company said it had overreported hundreds of deaths during the surge.

Until now, such pervasive failures escaped notice. In a first-of-its-kind analysis, USA TODAY has revealed ownership webs invisible to consumers. Problems across chains eluded federal officials overseeing nursing homes, who were focused on individual facilities during the pandemic.

THE PROJECT: DYING FOR CARE

Trilogy stood out among 15,000 homes

USA TODAY’s analysis started with the nation's more than 15,000 nursing homes to see which had reported the most COVID deaths during the winter surge a year ago.

After focusing on the largest chain operators, and isolating those with higher-than-average death rates, a much smaller pool emerged. Trilogy, which is based in the Midwest, had homes with more than twice the national average, a figure the company now disputes and says it corrected with the federal government this week.

SEE THE RATINGS: How did your nearby nursing home fare during last winter's COVID-19 surge?

Pressure to shrink staffing can affect care

Trilogy went further than any other major chain in reducing care hours delivered to residents before the pandemic. By the time the pandemic started, a typical resident in a Trilogy home was receiving about 45 minutes less care daily from nurses and bedside aides than the federal government recommends.

Under Trilogy’s staff reductions, levels of certified nursing assistants, called CNAs, fell to among the lowest levels of major operators. These frontline caregivers feed and bathe residents, help them to the toilet and change diapers, and make sure they do not get bed sores.

Academic research suggests that having a larger staff increased the odds of COVID-19 entering a nursing home. But once the virus got in, more care could keep residents alive.

How we did it: Read about the data-driven work behind USA TODAY’s nursing home project

At Waterford Place Health Campus in Kokomo, Indiana, Trilogy reported 29 deaths related to COVID between November 2020 and January 2021. HANNAH GABER, USA TODAY

Warnings were missed as facilities became COVID-19 zones

Half of Trilogy’s facilities were cited by health inspectors for violating COVID-19 safety rules in 2020, the first year of the pandemic. Among the lapses written up: nursing aides who dispensed eye drops, lifted patients to the toilet and fed them – all without properly cleaning their hands.

An outbreak in Kokomo, Indiana, lasted nine weeks and infected 88 residents at Trilogy’s Waterford Place Health Campus. By the end of January, 29 had died. Overnight, the facility turned into a scene from a sci-fi movie, with plastic barriers and bins set out for discarded masks and gowns.

A CNA recalled sick and frantic residents “on their lights constantly” calling for help. Two nurses and two aides on some days had to cover residents on three hallways, she said. Mornings passed in a blur of trying to deliver bites of breakfast off trays wrapped in plastic.

Safety lapses had played out for months, drawing citations from health inspectors who saw an aide chatting at a nurses station with a mask down in November, then in January during an active outbreak observed a resident without a mask wandering from room to room in the memory care unit before finally grabbing a used mask from the trash.

Share: Did your loved one die of COVID-19 in a nursing home? Tell their story here.

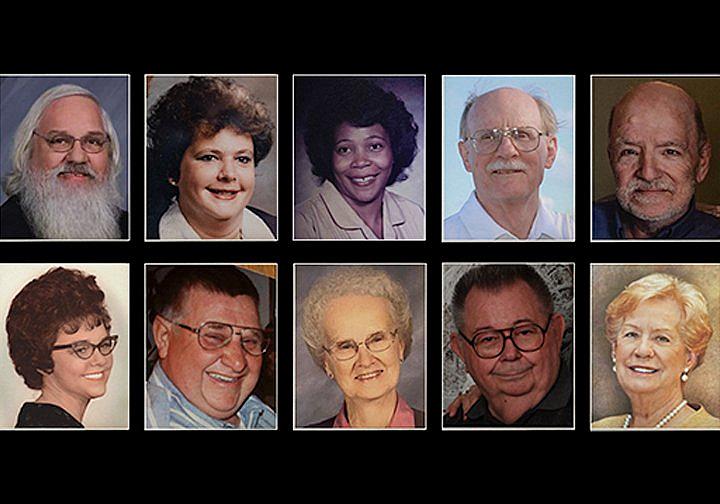

Photos of some of the 800 people who died at nursing homes operated by Trilogy CONTRIBUTED

A unique real estate business model

Even as deaths rose, millions of dollars continued to flow from Trilogy to a California-based real estate venture busy preparing its next investment pitch – a stock listing expected to launch this year.

In 2015, Trilogy was bought by a Real Estate Investment Trust, known as a REIT, in a $1 billion acquisition targeting the future health care needs of a booming senior population known as the “silver tsunami.”

Until Trilogy, major nursing home operators and their REITs had separated the real estate from the care delivered inside. But in this case, the REIT purchased not only Trilogy’s properties, but also the health care operations inside its campuses.

The approach meant a chance at bigger profits – as well as more risk in an economic downturn.

The real estate venture behind Trilogy came out of the winter surge with cash on hand and planning underway for its next business move. What is today called American Healthcare REIT proposes a major stock offering. It touts a now-$4 billion portfolio as potentially “the largest healthcare REIT listing in history.”

The stock listing proposed for later this year will explore Wall Street’s appetite for using a federal law enabling this arrangement, known as RIDEA, or the REIT Investment Diversification and Empowerment Act, in a big nursing home chain.

Letitia Stein reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 National Fellowship. This report was also supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. Jeff Kelly Lowenstein is the Padnos/Sarosik Endowed Professor of Civil Discourse at Grand Valley State University.