Arrest of 12-year-old on manslaughter charges highlights challenges in cases of kids

This article and others forthcoming on this topic are being produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Where Do Kids Get Guns? Inmates Reveal How Easy It Is

Fernandez case highlights the long-term implications of incarcerating youthful offenders

For many young homicide offenders, trouble easy to find

Many violent young offenders were 'born into dysfunction'

In children, trauma too often leads to tragedy

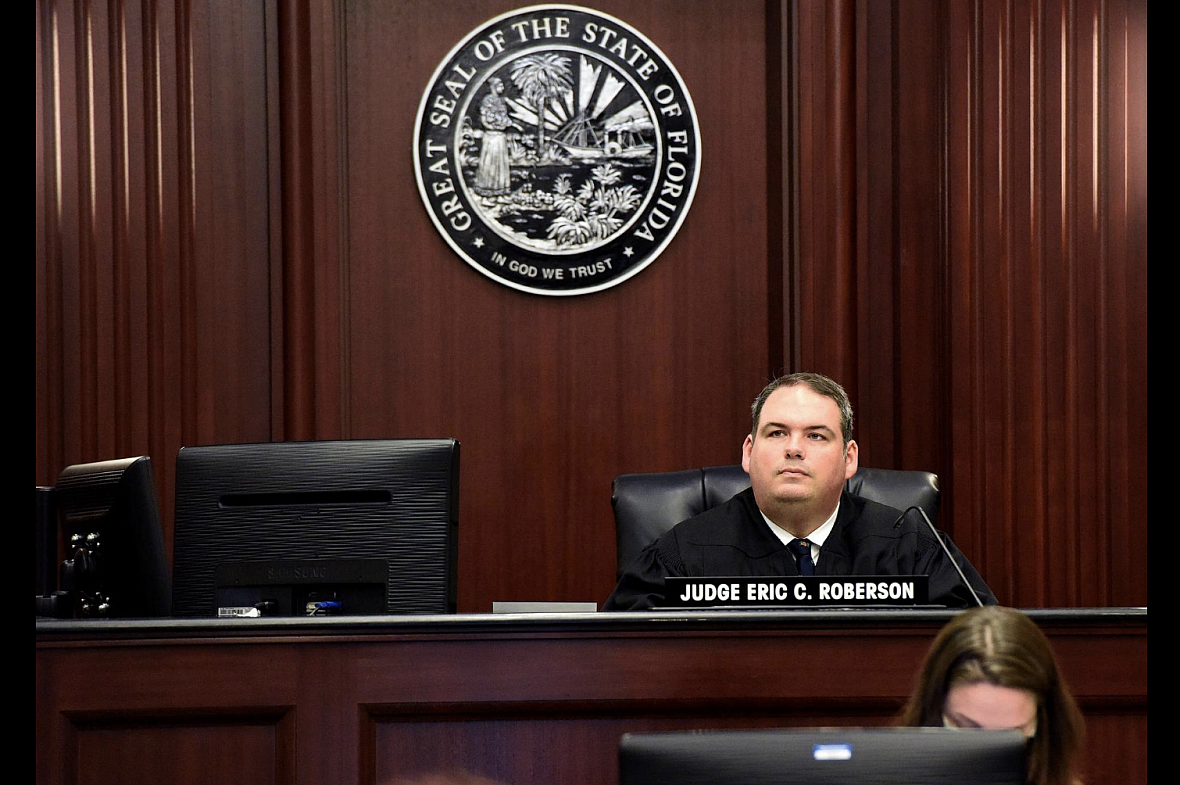

Juvenile Circuit Court Judge Eric Robertson presided at a hearing last week in the case of Tyron Calhoun, 12, accused in the shooting of 12-year-old Ra'Mya Eunice during a sleepover in April. Ra'Mya died nearly a month later. (Bruce Lipsky/Florida Times-Union)

An 11-year-old boy fetched a shotgun he’d found under the house and ran inside. He aimed it at everyone in the room. Then he pointed it at a 12-year-old girl.

“Say I won’t,” the boy said.

“You won’t,” someone answered.

That’s when he fired, according to the most recent police account of the April 30 shooting inside a Lackawanna home that left Ra’Mya Eunice bleeding from wounds to her head and face. A month later, she died.

At first, police described the shooting as an accident that happened while the girl slept on the couch during a sleepover at a home in the 100 block of Willow Branch Avenue. But new details emerged last week after police arrested Tyron A. Calhoun, now 12, on a manslaughter charge Oct. 20.

The boy nicknamed Baby Ty had been “playfully arguing” with Ra’Mya, according to the arrest warrant. The middle school student was picked up at his home on West 10th Street, the second local minor in a month charged with manslaughter in the death of another child. Because of Tyron’s age — 11 at the time of the offense — prosecutors can’t charge him as an adult with manslaughter; the minimum age for that is 14.

The State Attorney’s Office declined to discuss the specifics of the case, which remains in the juvenile justice system. It did issue a statement attributed to Chief Assistant State Attorney L.E. Hutton on how such cases are generally handled.

“We thoroughly review the facts and evidence of the case, take into account the juvenile’s age, and receive input from victims and law enforcement. We also try to learn as much information about the juvenile as possible, which includes obtaining medical, psychological, Florida Department of Children and Families, and school records,” Hutton said.

“Additionally, we attempt to talk with parents, teachers, or the juvenile themselves. Ultimately, after taking all of the available information into account, we make a charging decision that’s in the best interest of public safety and fairness.”

As Hutton’s statement highlights, cases like Tyron’s are challenging. One young child died, and another, even younger child is suspected to be responsible. How — and if — the courts should handle these cases remains open to debate.

Barry Feld, law professor at the University of Minnesota, said children are different than adults in their lack of judgment, appreciation of consequences, and reasoning abilities.

“One of the unfortunate aspects of kids is that they do dangerous and stupid and reckless things,” Feld said. “At the end of the day, he will probably be prosecuted, and it will be up to the juvenile court judge to come up with the appropriate jurisdiction.”

Dr. Judith G. Edersheim, a director at the Center for Law, Brain and Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital, said young children, adolescents and even older teens have different brain structure and functioning than adults. Taking all of those things into account and balancing them with public safety and crime deterrence is an issue the juvenile justice system is facing.

“Is using a gun when you’re 11 the same thing as using a gun when you’re 18 or 25?” Edersheim said, noting that brain science shows significant differences between an 11-year-old and a 20-year-old.

“It doesn’t take a neuroscientist to tell you if you have a teenager, they’ve impulsive and they’re a little reckless, and their decision-making is a little suspect,” she said. Add peers into the mix and it is even less likely a child will use logic and reasoning, she said.

The law is beginning to catch up with the science.

A series of recent U.S. Supreme Court cases have established as “irrefutable” that children are not legally nor developmentally the same adults, said Marsha Levick, deputy director and chief counsel of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia.

“Reasonable children are not the same as reasonable people,” Levick said, referring to a legal tenet called the reasonable person standard. “They don’t see risks and consequences the same way that adults do.

“Should he have been able to manage his behavior under those circumstances? He’s a child. One could query how much he even understands what happened in the moment he pulled the trigger.”

But that doesn’t mean a child can’t still be held accountable.

“It’s a natural instinct, and it’s an appropriate instinct,” Levick said. “But we hold children accountable in developmentally appropriate ways.”

How young is too young?

Liz Ryan, president and CEO of Youth First, a national advocacy campaign to end the incarceration of youth, said when people think of the juvenile justice system, they tend to think of teenagers. Any younger than that, Ryan said, and kids should really be treated in the child welfare system.

But, in most states, there are no laws that prevent very young children from being prosecuted. Washington, D.C., and 32 states — including Florida — have no restrictions on the minimum age for delinquency. Eleven states require a child be at least 10 years old. North Carolina only requires a child be at least 6.

“There should be a threshold limit. Particularly, a limit around juvenile court processing, but also around if that child should also be placed in a detention or correctional facility,” Ryan said. “For purposes of child protection and also for young children, they are not even capable of knowing what’s going on in the court.”

Stephen K. Harper, executive director of the Florida Center for Capital Representation at Florida International University, said he’d be surprised if Tyron — or most 11-year-old kids — could actually understand court proceedings. They likely don’t know who their lawyers are, what a judge does, the role of a prosecutor or the meaning of a plea.

“I don’t think 11-year-olds are competent to stand trial, certainly in adult court, and even in juvenile court,” Harper said. “They’re far too young to understand the consequences of behavior. ... He’s goofing around, he doesn’t understand the full implications of why it happened.

“It’s literally tragic kid stuff. I don’t believe that kind of thing belongs in court. It’s horrible. He’s going to regret it for the rest of his life.”

A MacArthur Foundation study found that before age 16, “young people are significantly less likely to appreciate the nature and importance of legal proceedings, provide relevant information to lawyers and make well-reasoned judgments about their individual circumstances.”

Harper pointed to a Florida statute that makes stipulations for a child “in need of services.” Under this statute, the Department of Juvenile Justice would still take custody of the child, but he or she wouldn’t be treated as a criminal and would receive necessary help.

“I would say that’s the best way to go with an 11-year-old,” Harper said.

‘You’ve got a dead body’

When someone dies in a case like this, Feld said, prosecutors have to do something.

“You’ve got a dead body. Once you have a dead body you have to do something about it,” he said. “Basically, you’re either going to think about a mental health system, which for kids is pretty inadequate for kids in every state in the country. And you’ve got a juvenile justice system. In most states, it’s the de facto mental health system.”

Feld said there are programs that can help young people who have committed serious crimes, typically run by nonprofit service providers and not the state. In Florida, the Department of Juvenile Justice can have jurisdiction over young people until age 21.

Simply locking up a child in a youth prison is “the least effective way to deal with young offenders’ problems,” he said.

“They have been evaluated extensively everywhere in the country and the consensus of research is that if you can deal with a kid in the community, in a small residential facility ... you’ve got a much better likelihood of producing a better outcome,” Feld said.

Edersheim, who is a psychiatrist and a lawyer, said children are sponges, and their environments help to shape who they become. During adolescence is when kids begin to understand what it is to be an appropriate adult.

In Massachusetts, any child who enters the justice system is given therapy that helps them control their emotional responses, called dialectical behavioral therapy. The results have been “spectacular,” she said.

Other cases of very young offenders

Another 14-year-old, Christian Ashley, was arrested earlier this month on manslaughter charges in the death of his friend Henry Atkins. According to the arrest warrant provided by the State Attorney’s Office, Christian was playing with a firearm with his finger on the trigger when the gun fired and struck Henry in the chest, killing him.

Like Tyron’s, Christian’s case has remained in juvenile court.

Two other high-profile cases involved murder charges, and the children were indicted by grand juries. Cristian Fernandez and Sharron Townsend were both 12 when they committed the crimes to which they pleaded guilty. There is no minimum age for indictment for crimes punishable by death or life in prison.

Notably, State Attorney Melissa Nelson was a part of the defense team for Fernandez that negotiated his first-degree murder charge down to a manslaughter plea. He received juvenile sanctions in the 2011 death of his 2-year-old brother and is set to be released from a juvenile facility in January at age 19.

Nelson said last year while campaigning against former State Attorney Angela Corey that, “With Cristian Fernandez I was very proud of the role I played correcting a miscarriage of justice.”

[This story was originally published by Florida Times-Union.]