Cultural tradition traps Chinese elder-abuse victims in U.S.

Elder abuse, a growing but hidden problem for Chinese seniors in the United States, often originates when adult children here reject the tradition of filial piety. This is the second story of a two-part series. Read Part 1 here.

New American Media/Sing Tao Daily

The scourge of family elder abuse affects as many as to 2 million people in the United States, as well as up to 5 million seniors subjected to financial exploitation.

Shame, fear and secrecy surrounding elder abuse have generally made it difficult for experts to obtain exact figures. For Chinese and other Asian American families, the strong influence of traditional culture brings additional challenges to prevention and protection.

“Chinese culture gives higher value to the unity of the family than the individual themselves. It is uncharacteristic for Chinese parents to formally charge their children for abuse,” said Xinqi Dong, a researcher at the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging, in Chicago.

For this reason, said Dong, “it is more difficult to discover such cases and provide help.” These seniors often remain silent about their plight.

One Silent Victim

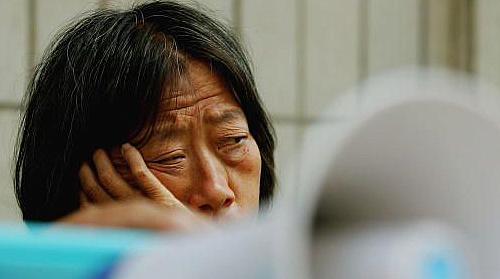

One of these silent victims is Jinfu Liu, age 75.

Skinny with receding gray hair, the quiet Liu would just look like an ordinary Asian man, except for the scar on his cheek. The scar makes him extremely embarrassed in front of his elderly friends because it was put there by his son’s fist.

In the past two years, his son has beat Liu five times. “Once he punched me, and I fell on the floor and fainted. When I woke up, it took me a long time to figure out why I way lying on the floor,” said Liu.

Every time he was attacked, Liu told himself he’d call the police next time. But he never did. If the latest attack had not left him with a bleeding cheek, he would not have sought help from Gin Lee, a specialist at the Chinese Americans Restoring Elders (CARE) Project at the Indochina Community Center.

However, when Lee suggested helping Liu apply for a restraining order from the court, the abused senior declined.

“I don’t want leave my son a bad record. It will affect his future,” said Liu. “My son was actually a good boy when he was young. He respected me a lot, and I also secretly favored him over his siblings.”

Lee was not surprised. “Many Asian seniors like to keep silent when they are abused by their children. Even when they have to ask for help, they won’t like the cops or the court to get involved. No matter how they are treated by their children, they always think for the children,” she said.

Abuse Recent to Asian Countries

“Everyone knows revering seniors is a significant part of the Asian culture, so the other side is easily neglected, said Tazuko Shibusawa, an associate professor of social work at New York University, who studies issues affecting Asian seniors.

“In many Asian countries like Japan, people hadn’t known the existence of senior abuse until the recent years,” Shibusawa went on.

In one study, the Rush Institute’s Dong found that willful neglect—such as refusing to provide the person food or medicine--is the most common type of abuse among Chinese seniors, followed by emotional abuse and financial abuse. Physical abuse is rare. These findings are no different than among whites.

“The more seniors rely on their adult children, the more likely they are to become abuse victims,” said Peter Cheng, executive director of Indochina Sino-American Community Center, which operates the only senior protection program in the Chinese community in New York.

Cheng continued, “Many Asian seniors hold green cards sponsored by their children, and they don’t speak much English and have few other relatives or friends they can go to. This makes them more vulnerable than seniors in the mainstream community.”

Dong noted that in addition to experiencing stress from immigration in later life, filial piety, although highly valued in Asian cultures, can become a fuse for abuse.

“Filial piety requires children to obey the parents and support the parents financially. These are not the obligations of children in the American culture. When the young people cannot meet the expectation of the seniors, it often leads to conflicts,” said Dong.

Pauline Yeung, an attorney with Grimaldi and Yeung, a New York law firm specializing in aging and disability, said, “In most of our senior abuse cases, the victim is exposed during the dispute among siblings over the assets of the senior’s. Few Asian seniors would come to us themselves,” said Yeung.

Adult protection specialists in other cities voice the same frustrations. For example, Self-Help for Elderly, a service agency in San Francisco’s Chinatown, takes on about three elder abuse cases every month. They refer most cases to the city’s Adult Protective Services agency, to which social workers are mandated to report such cases.

“It’s very rare to see Asian seniors come to us to make complaints,” said Vivien Wong, Self Help for the Elderly’s director of social services.

Community Responsibility

Other than the issue of saving face and concerns for their adult children, the silence of Asian victims also stems from their ignorance of the concept of senior abuse. Many times, they don’t even realize they’ve become victims.

Attorney Akiko Takeshita, observed, “When abused, many Asian seniors would think this is their fate, or they’d say, ‘My children are rude to me.’”

Takeshita, a lawyer with Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, a legal assistance organization in the San Francisco Bay area, continued, “But if your children take away your jewelry or beat you up, it is not simply ‘being rude.’”

Important as it is, raising awareness about elder abuse is not an easy task. Many seniors don’t like to attend workshops on elder abuse because it might signal that they are victims—“face losing” in their perspective.

Service providers have to be creative. “When we offer a workshop, we always tell the audience that this may not be for them, but they can help others after they learn more about senior abuse,” said Vivien Wong of Self-Help for Elderly.

A culturally competent approach is the key to victim protection. “Many abusers are family members, and the Asians believe what happens in the family stays in the family,” Takeshita said. Because victims often don’t want to punish their abusers, Takeshita said, service providers also need to work with the adult children, “so when we are out of the picture, they still can live together.”

Sometimes, a social worker’s understanding of the victim’s language and culture can save a life. Ask 67-year-old Yuying Sun. She married a Chinese American and moved to the New York five years ago, but Sun said her husband and his children treated her like a servant.

After her husband beat her, she was sent to a mental health evaluation institute in a hospital in the Bronx, thanks to his son’s 911 call and false report to the police.

Sun, who doesn’t speak English, was placed in a locked unit with mentally ill patients and no interpreter. Lee, of the Indochina Community Center, heard about her case through a services organization in the Bronx and went to the hospital to see her.

Sun told her she was thinking of hanging herself. “I thought my life was totally collapsed and could not see any hope. If she hadn’t rescued me, I’d have been dead now,” said Sun, who has since been fighting in court for her rights.

“We may only be a small program, but we want people in the community to understand, if you and I don’t stand up to fight against senior abuse, many lives of the seniors would be withering in silence,” said Lee.