Culver City Walks, Not Runs, Towards Transportation Sustainability

Undergoing an aggressive revitalization of its Downtown area and improved transportation planning, Culver City has transformed itself into a place that's popular among residents, families and tourists. This is the third of a three-part series on Culver City's Policies for Livable Active Communities and Environment grant.

Part One: First Steps in Culver City, Connecting Downtown to the Expo Station

The start of the Downtown Connector at the intersection of National Blvd. and Wesley St. The bicycle friendly street contains Sharrows, signage, narrow roads, and some traffic calming.

Following the decline of the studios in the 1960′s and 1970′s, Culver City had to reinvent itself. In the 1990′s, the city once commonly referred to as “The Heart of Screenland” undertook an aggressive campaign to revitalize their Downtown area that was mostly successful in attracting businesses and tourists to bolster the city’s economy. Today, nearly 40,000 people call Culver City home, and it’s widely thought of as a safe place to live and a good place to raise children.

Despite its reputation for embracing New Urbanism (in 2007 the New York Times called the city a “nascent Chelsea”), Culver City had never embraced transportation planning for cyclists and pedestrian. In fact, when the City approached the L.A. County Public Health Department about a PLACE Grant, it had never had either a bicycling or pedestrian element in its Master Plan. While critics of the plan, including some of the people that helped create it, complain that the plan isn’t as progressive or specific as it should be, for a city that was literally starting with no foundation or advocacy community, to create change this is a crucial first step.

The lack of a bicycle and pedestrian plan of any sort was a major reason Culver City was awarded the PLACE grant, because in many ways it is a city that is doing well. Obesity statistics, especially those for grade-school age children are lower than the national average. In addition, Walk Score, an organization that looks at waklability on a national scale recently ranked Culver City as a “very walkable” community.

As any parent of a toddler can tell you, you have to learn to walk before you can run. When it comes to planning for people-powered transportation, Culver City is walking, and the fruits of that walk are a brand new Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan.

Or, as Ron Durgin, President and Co-Founder of Sustainable Streets and a member of the master plan’s citizen advisory committee, put it, “These are the broad strokes they’re going to need to move forward.”

It’s long been accepted that auto-dependency leads to poor air quality, as pollutants spewing from tailpipes have been blamed for a laundry list of human ills including many lung conditions (such as asthma) and neurological disorders (such as autism.) However, modern public health experts are looking at the ills of car dependency in a new light, noting that areas with poor sidewalks tend to have higher obesity, that there is a correlation between a drop in children walking and biking to school and an increase in childhood obesity and that cities with more bike lanes have healthier overall populations. Some research even points to improved mental health for those who take regular walks or bike rides.

With $320,000 in public health money in-hand, the City embarked on a three-year process to create its first Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan, which serves as both a collection of projects that the city hopes to complete in the next five years and a vision for a Culver City that encourages walking and cycling in a very real way.

“The City of Culver City is extremely grateful to the LA County Department of Public Health’s PLACE program for providing us with grant funding. The County made it possible for us to create the City’s first Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan (BPMP)’” writes Culver City Mayor Michael O’Leary. ”The process of developing the BPMP engaged the community like never before in bicycle and pedestrian issues. The resulting documents will help shape the City for years to come by communicating clear goals and by identifying priorities for improvements in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. We are dedicated to providing educational, encouragement and enforcement efforts in the future.”

The mayor’s support of walking and cycling extends to his life outside public service. During Bike to Work Day, the restaurant and bar he owns had a special happy hour for any commuter who arrived on bicycle.

We’ve already discussed how the city’s public process created the “Downtown Connector” project that gave birth to well-marked bike routes to connect the future Expo Station to Downtown Culver City (and east Culver City residents to their schools and parks) and led to the creation of the Culver City Bicycle Coalition. Now we’ll examine the plan itself.

In addition to five public meetings, Culver City and their project consultants also conducted a series of bicycle and pedestrian counts to inform their project process. To examine a bicycle and pedestrian plan such as this, there are several things we have to examine. The first is whether the plan is putting in infrastructure in places that make sense. Second, we have to look at whether the projects themselves make sense. Last, because this is a smaller city that is basically surrounded by the mammoth City of Los Angeles, we need to see whether or not their infrastructure plans are in sync with those of their neighbors.

“They were kind of going together in the same process,” explains Culver City’s John Rivera, the PLACE Grant Coordinator for Culver City. ”The L.A. plan was adopted about four months after ours. We used Alta Planning that was the consultant used by L.A. City for their plan. We kept track of them, we looked at their maps as they were proceeding. We tried to make sure that each of our bikeways met up with an L.A. bikeway.”

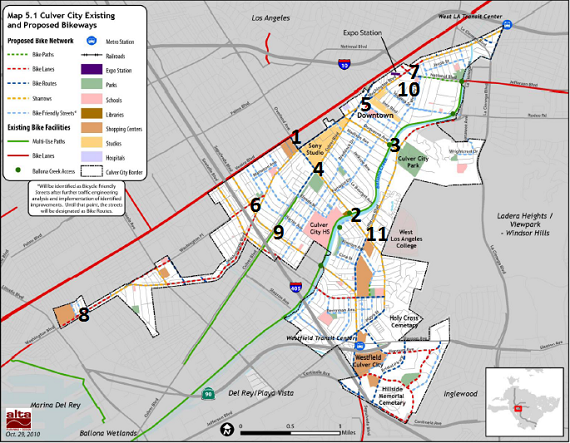

The above map from the city’s newly passed Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan shows all of the existing and proposed bicycle routes in the City of Culver City. Streetsblog added the numbers to show the top 11 locations for bicycle travel based on the May 2009 bicycle and pedestrian counts the city completed. As you can see, the city had no bicycle infrastructure of its own before the creation of this plan and the completion of the Regional Connector Project (which Streetsblog covered on Tuesday.)

Culver City claims it can implement the entire plan in the next five years, which would really bring a dramatic change in the city’s infrastructure. Currently, there are a paltry 4.2 miles of bike infrastructure within the city. If implemented, the Culver City Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan would increase the mileage of bike infrastructure nearly ten-fold to just over 41 miles. Culver City has a firm deadline when they hope to complete plan implementation, November of 2015, five years after passage of the plan.

The only existing infrastructure was a small portion of the Venice Boulevard Bike Lanes, the Ballona Creek Bike Path and a portion of the Culver Boulevard Bike Path, all of which connect to larger infrastructure outside of the city. Looking at the map, you can see that the proposed bicycle network all connects to each other and eventually the large existing bike lanes and bike paths. A recent study by urban planner Gian Claudia-Sciara published by the University of California Transportation Center shows that creating complete networks, where cyclists don’t have to leave the network to travel large distances, is a key to encouraging new cyclists thus increasing the amount of exercise a community gets through transportation choices.

The projects also provides a network of local bicycle facilities designed specifically to encourage cycling within the city. The routes providing connections to Venice Boulevard, the Downtown, or the Bike Paths are really designed for people traveling to and from Culver City, but the internal network is perhaps more important in encouraging new riders, which is a key component of a public health component to transportation planning.

This is where one of the concerns with the Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan comes into play. Most of those local connections are designated as either “Bicycle Routes” or “Bicycle Friendly Streets.” Of the 36.9 miles of infrastructure in the plan, over twenty miles of the infrastructure are either routes (5.6 miles) or “Bicycle Friendly Streets” (14.6 miles).

Most bike facilities are clearly designed. Bike paths create bikeways that are separate from regular travel lanes and completely remove cars from bicycle traffic. Bike lanes and Sharrows both use paint to create safe space for bicycles parallel to or in the middle of, mixed use travel lanes.Unlike bike paths. However, both bicycle routes and “Bicycle Friendly Streets” don’t have a specific treatment. Bicycle Friendly Streets could be as simple as a route marked with signs or could have a series of traffic calming devices, Sharrows, road signs, directional signs, traffic circles, chicanes, loop detectors, diverters, etc.

In short, nobody is 100% certain what a lot of the plan will look like when it is implemented. In fact, the term “Bicycle Friendly Street” is not one in common usage with bicycle planners across the country, but is a favorite term of Alta Planning and Design. Alta Planning is not just the consultants for this plan, and the recently passed plan of the City of Los Angeles and pending plan of the County of Los Angeles.

Fortunately, the plan does give us some hints what a Bicycle Friendly Street will look like. The recently completed Downtown Connector is designated in the plan as a series of “Bicycle Friendly Streets” and it contained a series of Sharrows, “bike route” signs, directional signs, and even traffic calming at the beginning and end of the Connector. If every “Bicycle Friendly Street” in the plan is treated as the Regional Connector, Culver City’s road network might be almost unrecognizable in five years.

Secondly, the Plan does give detailed project descriptions for both the 5 “Tier 1″ bicycle and pedestrian projects called for in the plan. Below is the design of a “Bicycle Friendly Street” on Braddock Drive, a residential street, between Sawtelle Boulevard and Irving Place. Braddock is the longest residential street in Culver City, and despite it being a popular route for students, is also used as a cut through when Washington Place is crowded.

The bicycle plan for Braddock calls for a lot more than just signage, and would encourage bicycle riding by discouraging all but local traffic through the area with the curb extension and by improving crossings for cyclists. Two of the top mental barriers to new cyclists riding bicycles on the streets. But while the plan contains details for the Braddock Bicycle Friendly Street and four other bicycle projects, the minimum that is required to meet the Bicycle Friendly Street designation is road signs marking the street as a bike route.

A new series of bicycle and pedestrian counts were completed in May. While final results haven’t been released yet (Streetsblog will provide coverage when they do) city staff confirmed that even before much of the new infrastructure has been put in, the city has seen a modest rise in bicycling in the past two years. Sustainable Streets’ Durgin jokes that as more cyclists take to the street, and more infrastructure is placed on those streets, “next time around we’ll really grind them” and create a more sustainable plan.

Anecdotal evidence also points to more people, both cut through commuters and residents, walking and bicycling on the street. ”In general its improving, we’re seeing more and more cyclists on a daily basis. We’ve always had a steady flow of commuters, from the east and the south, but now we’re starting to see more Culver City residents riding on a regular basis,” reports Jim Shanman, a founding member of the Culver City Bicycle Coalition.

The pedestrian portion of the plan received a lot less scrutiny and staff time than the bicycling plan. Part of that is that bicycle projects are by their nature less controversial because they don’t have to address conflict issues at the level the bicycle plans do. It is also partly due to the fact that with or without a long-term pedestrian plan, Culver City is a decent place to take a walk. Scott Wyant, a member of the city’s planning commission and of the Citizens Advisory Committee for the Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan joked that “We were often referred to as the Bike Committee.”

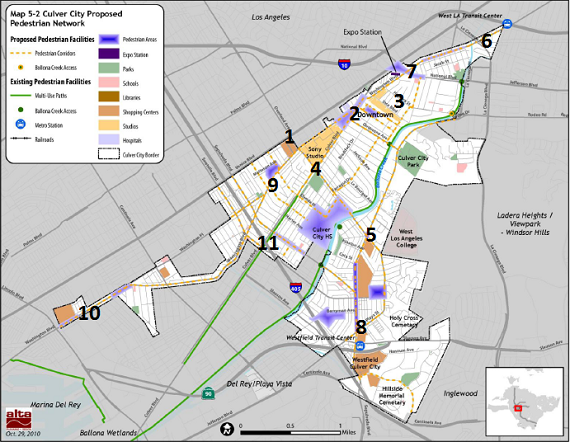

As with the map of planned bicycle improvements, Streetsblog has placed the top eleven places where pedestrian counts were taken during the May 2009 counts. There is a lot of overlap with the most popular places to find pedestrians and cyclists, and in places where new infrastructure is proposed. Scientific studies have shown that many of the same barriers that discourage bicycling also discourage walking such as high traffic volumes, noise and unsafe street crossings.

Thus, we see two maps that call for bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure on the same streets. As with the bike map, there are really two maps above, one is designed to provide routes for people to move about the city, and another is designed to improve neighborhood access to schools, parks and job centers.

However, the plan has similarly vague language to describe what will actually be done to improve conditions on these “pedestrian corridors” that will make up the new pedestrian friendly Culver City. But as with the bicycle projects, the plan does give detailed layout on 5 “Tier 1″ pedestrian projects. Here are the planned improvements for Braddock Drive.

On Braddock and the other five Tier 1 projects, the focus is on the areas where pedestrians and other road users are most likely to get into conflict: at intersections. This makes sense because this is where pedestrians are most physically vulnerable and the place where mental barriers to walking can be created by the real or perceived physical danger.

Wyant was most interested in joining the advisory committee because he was concerned that pedestrian issues would be overlooked in the plan, but when the final plan was unveiled, he expressed full support for it. ”I’m happy with this plan. It’s a good plan that can do a lot for the city,” Wyant continued that the makeup of the staff at Alta Planning, city staff and the Advisory Committee had a lot to do with why he feels the plan will work. ”We had good people making the plan who worked in good faith. In the end the plan was as good as the people.”

While cycling advocates, and a lesser extent pedestrian advocates, are very supportive of the Master Plan, there are some complaints that when it is compared to some of the more progressive cities in the Southland, such as Santa Monica, Long Beach, and Pasadena.

Dino Parks, a member of the Plan’s Citizen Advisory Committee and of the Culver City Bicycle Coalition, explains. ”In some ways, the projects are low-hanging fruits.” “In no places are they talking about widening roadways or taking away a traffic lane to make space for bikes.”

In short, the city is willing to begin to make more space for bicycles and pedestrians, but not to take the step of removing car capacity outside of some traffic calming on local streets. Even in the City of Los Angeles, known world-wide as the car-culture capital of America, the Bike Plan calls for removing some mixed-use travel lanes.

On the advisory committee, Parks had pushed for a radical reconfiguration of Washington Boulevard that would have doubtless made things safer for cyclists and may have gotten more people to bike on the congested east-west alternative to Venice Boulevard. However, the plan was, “much to hot to touch.”

Other complaints are that the city wasn’t willing to push the limits on what infrastructure was possible. Forget cycle tracks, or separated bike lanes as they’re more commonly called, Culver City wouldn’t consider signage that reads “Bicycles allowed full use of the road” because they aren’t part of the approved signage in the state of California. ”Full use” signs are popular in Northern California and are used locally in Hermosa Beach. Similarly, the city wouldn’t consider placing Sharrows on streets that don’t have certain parking patterns to meet federal standards. Those standards are changing, and Glendale is already placing Sharrows on streets without curbside parking; but Culver City won’t consider any infrastructure that hasn’t been approved at the state and national level.

But even as he criticizes the plan for not being as progressive as he would like, Parks readily concedes that the plan is a big step forward for the city. “If all of those projects are implemented, it would contribute to a more bicycle friendly city and could be the nexus to encourage more people to ride and walk.”

The Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan enjoyed strong support on the Culver City Council. Rivera points out that support for the plan goes back years. ”The City Council authorized going for the PLACE Grant unanimously. They were very supportive from the very beginning and ultimately they approved the plan unanimously with no changes. They saw the need for it, and they wanted to see improvement in these areas.”

However, because the plan doesn’t call for the removal of any travel lanes, and doesn’t give details for many of the proposed projects, there could still be political battles over the implementation of the plan.

In March, just four months after the Bicycle and Pedestrian Master Plan was passed by the city, Councilman Scott Malsin proposed to weaken the plan with a motion that would have watered down the plan by removing bike lane designations for parts of Washington Boulevard and allow the Council to change the plan for any reason if a plan proves unpopular. Of course, a City Council can always amend a portion of the city’s planning documents, but passing such a motion sends a strong message to potential funders that the City isn’t as serious about the plan as they could be. The motion was eventually pulled from consideration, but it exemplifies some of the battles that could be coming.

Meanwhile, city staff is working to bring in the grant dollars needed to make the plan a reality. While there is a top ten project list in the plan, staff looking at different options to try and get project-specific funding to begin changing the DNA of its streets. For example, in June the city successfully won a $500,000 grant from the Baldwin Hills Conservancy to fix the dangerous intersection of Hetzler Road and Jefferson Boulevard. Jefferson and Hetzler was not a top intersection, either in terms of existing usage by cyclists and pedestrians or project priority. But the funds existed, and staff recognized a need so they pursued those funds.

The Culver City Bicycle Coalition supports the city’s efforts to chase funds where available rather than to singularly focus on the “Tier 1″ projects. ”We recognize the city isn’t going down a checklist from one through ten to get those projects done,” explains Shanman. ”As long as the progress is steady and continual, we’ll be happy.”

The city has also had success pursuing funding for a $450,000 Safe Routes to Schools grant for Linwood E. Howe Elementary School, the elementary school at the northwest end of the recently-completed Downtown Connector. The city is also pursuing a $500,000 grant for a city-wide childhood education campaign aimed at encouraging safe and healthy options for students to walk and bicycle to school.

Originally the educational grant was paired with a grant that would have improved infrastructure for Culver Middle School on the west side of the city. However, a vocal group of opponents lobbied the City Council, and the proposal was paired down to just include the educational program. While the Culver City Bicycle Coalition lobbied hard for Culver Middle School safety plan, city leadership wasn’t ready to engage in the political battle necessary to push an application against local push back.

But even though advocates were disappointed that the full grant application didn’t move forward, they are happy the city is moving forward with quality applications. ”We never got our Safe Routes to Schools grants funded before. If we earn this grant, it would be almost $1 million in two years,” offers Sahli-Wells. City staff confirms that a future Safe Routes to Schools Grant for Culver Middle School could be back completed for a fall grant application cycle.

In summary, it’s fair to say that Culver City isn’t about to supplant Long Beach as the bicycling capital of Los Angeles County, but that it’s come a long way in a short amount of time. Combining the funded Safe Routes to Schools project by Linwood E. Howe Elementary School, with the improvements planned for the Jefferson/Hetzler intersection and surrounding area funded by the Baldwin Hills Conservancy, and the Regional Connector the bicycle infrastructure for the city will increase by 50% from the existing conditions when the PLACE Grant was awarded in 2008.

It might not be running yet, but Culver City is walking towards a sustainable future. If it manages to fund and complete this plan in five years, the “Heart of Screenland” will also be home to a sustainable transportation grid.