From deadly mines to dangerous bedrooms

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Sara Israelsen-Hartley, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

How looking at an invisible gas could bring change into your home

Clouds spew from a cooling tower at PECO’s nuclear generating station.

George Widman, Associated Press

Editor’s note: This investigative report was produced with support from the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship.

SALT LAKE CITY — Hundreds of years ago, at the base of the Erzgebirge Mountains between Saxony and Bohemia, 14th century miners carved their way into the boggy, tree-covered hillsides, pulling out rocks laced with shimmering ribbons of tin and silver.

Small mining towns had flourished for hundreds of years, but when rich veins were discovered on the craggy now-Czech Republic side, miners and their families flocked to the area, quickly turning the new town of Joachimsthal into one of Europe’s largest mining centers.

Before marching into the darkness of the hollowed-out earth, workers called to each other: “Ich wünsche Dir Glück, tu einen neuen Gang auf” — a wish to open a new lode, and return safely after the day’s work.

For several decades the luck held and silver poured out of the mines, filling Saxony’s coffers with silver coins and guaranteeing a livelihood for strong, young workers.

Yet after years in the mines, which were now producing a strange black mineral, workers began dying.

Many were convinced the sickness afflicting miners’ lungs came from evil mountain spirits.

Women began knitting lace veils for workers to wear while underground, but despite their efforts, wives often buried multiple husbands.

By the late 1500s, early physicians had discarded the theory of evil spirits and hypothesized that deaths were caused by problems with the air in the mines.

Only hundreds of years and numerous studies later would experts realize that the mysterious black material miners had labeled “pechblende” was riddled with uranium, and that the sickness was not the result of mountain demons, but of radiation exposure, often co-occurring with silicosis or tuberculosis.

By the 1930s, it was clear that radon was to blame for the high lung cancer rates among Eastern European miners, says Dr. Jonathan Samet, dean of the Colorado School of Public Health and chairman of the Committee on Health Risks of Exposure to Radon.

But it wasn’t until 1984 in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, that U.S. scientists realized the dangers of radiation exposure extended far beyond the mines.

That year, the new Limerick nuclear power plant was under construction. In preparation for the radioactive material the plant would soon receive, workers had installed radiation detectors to ensure workers wouldn’t leave contaminated.

But when employee Stanley Watras walked through one December day on his way in, the alarms blared.

Confused, plant workers measured Watras and found high levels of radiation all over his body.

Knowing the radiation couldn’t have come from the plant, a crew later went to his home to investigate, finding areas inside with radiation levels more than 1,000 times the recommended exposure level — the result of accumulated radon gas.

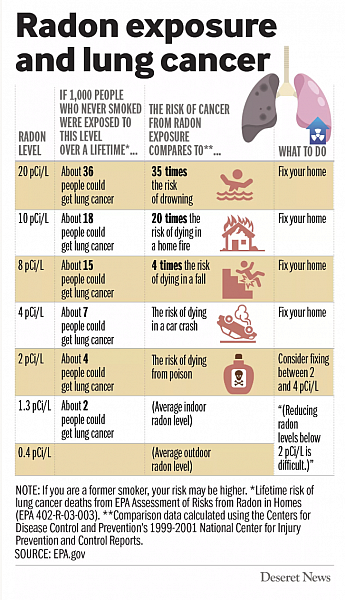

In 1986, Congress asked the EPA to determine the extent of the indoor radon problem, and after surveying nearly 5,700 homes, the EPA announced that an estimated 6% of homes — 5.8 million homes in 1990 — had potentially dangerously high levels of radon.

Determined to discover what that meant for people living in those homes, Bill Field, a professor at the University of Iowa, began what would become a seminal study on indoor radon exposure and health risk.

From 1993 to 1996, he followed 413 women in Iowa who had been newly diagnosed with lung cancer and 614 women without cancer, and monitored radon levels in every home — where the women had all lived for at least 20 years.

After adjusting for age, smoking and education, Field and colleagues found a 50% increased risk for lung cancer based on long-term exposure to elevated radon levels.

Subsequent case-control studies, including a European analysis of 13 cases comprising 7,148 cases of lung cancer and 14,208 controls, as well as 1,050 cancer cases from two Chinese studies and 3,662 cases from the U.S. and Canada all show a similar connection — the greater the radon exposure, the greater the risk of cancer, with no safe level of exposure — whether you’re in a mine or a basement bedroom.

[This article was originally published by DeseretNews.]