Help eludes father until son ends up behind bars

Seven years after voters passed Proposition 63 -- the landmark legislation that was supposed to radically improve mental health care in the state -- California is facing a deepening statewide mental health crisis. As the state struggles under the weight of a lingering recession and an enormous deficit, county mental health programs often fail to provide care for even the sickest patients. In many cases, the minimal safety net that used to exist is disintegrating.

In the absence of care, many people with mental illnesses are instead cycling in and out of jails and emergency rooms. They are receiving treatment patched together by primary care providers.

This series describes why these cuts are occurring and how they are impacting people with serious mental illness and their families. Articles in the series writen by Jocelyn Wiener include:

Part 1: Mental health care breaking down in Stanislaus County

Part 2: A family's never-ending cycle

Part 3: Help eludes father until son ends up behind bars

Part 4: A shining light in Modesto

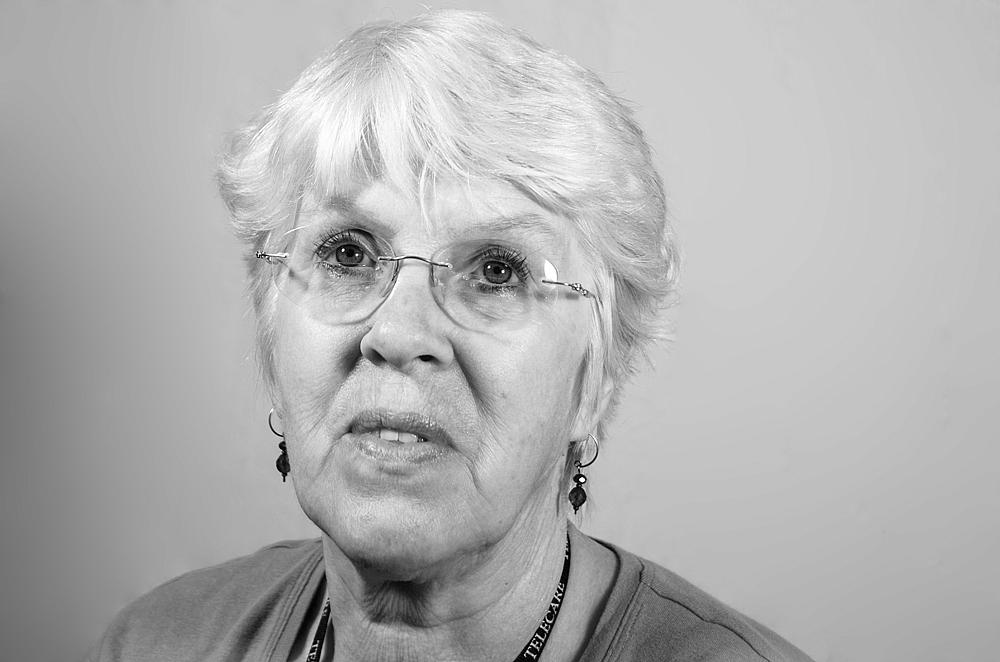

MODESTO -- Joyce Plis, executive director of the Stanislaus County chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, attends as many court hearings as she can, advocating on behalf of mentally ill individuals, helping family members navigate the legal system and talking with judges and attorneys on both sides about the individual defendants' illnesses.

In 2010, she went to bat for the 32-year-old schizophrenic son of Richard Curtis, a 59-year-old construction worker. Curtis said that before he met Plis, he watched his son argue constantly, lose weight, struggle to concentrate and speak of demons.

Seeing his son's condition worsen, the elder Curtis went through the phone book, asking various organizations for help. But because his son was uninsured, it seemed to Curtis that everyone he called sent him somewhere else.

By the time he found Plis, Curtis said, his son was already in jail, facing a third strike for battering his son's mother. The son said he pushed her during a fight. A third strike could mean life in prison.

"I was too late," the elder Curtis said. "Things spiraled out of control."

The younger Curtis said he sat in the county jail for a few months before he eventually arrived at the Atascadero State Mental Hospital. Deputy David Frost and various medical personnel were kind to him in the jail, he said, though he felt that certain deputies would mock him and the other mental health inmates.

"I don't ever want to be like that again," he said.

Once in the state hospital, the son said his condition stabilized enough that he was able to face charges

He ended up pleading no contest, being spared the possible life sentence, and spending several more months behind bars.

Upon his release, he was able to receive medication through Stanislaus County's medically indigent program, he said.

He said he has been rejected repeatedly from Social Security, which would allow him to qualify for Medi-Cal and more extensive county services.

This article was originially published by The Modesto Bee.