Importing Doctors: Foreign physicians in Kern share their stories

Read why the United States imports so many foreign doctors. California fellow Kellie Schmitt completed a multi-piece series on the United States' reliance on foreign-doctors. Physicians from far-flung corners of the globe have ended up practicing medicine in Kern County. These pieces trace the journeys of several international medical graduates -- exploring how doctors from across the world ended up in and around Bakersfield, and what they enjoy about their new lives here.

Part One: More than half of Kern physicians were foreign-schooled

Part Two: Are we creating a foreign brain-drain

Part Three: Pace of foreign-physician influx may slow

Part Four: KMC's multimillion dollar deal with Caribbean school marks part of controversial trend

Part Five: Concerns about the quality of Caribbean schools persist

Part Six: Many American students turn to Caribbean medical schools

Part Seven: Foreign physicians in Kern share their stories

Part Eight: From Sudan to Bakersfield

FROM BURMA TO BAKERSFIELD

It all started with a Burmese pulmonologist who traveled to Bakersfield to work for Kaiser Permanente.

There was so much work that he helped recruit his friend, another pulmonary specialist who attended the same medical school in Burma. That doctor brought his wife, a Burmese internal medicine physician.

She was lonely, though, and so she convinced her sister -- an internal medicine physician -- to come to town with her husband, yet another primary care doctor.

And that's how a cluster of Burmese doctors formed in Kern County.

On weekends, those physicians often gather to play tennis, hit a round of golf or dine at someone's home. Sometimes they'll travel to Los Angeles or head to the beach together for a weekend.

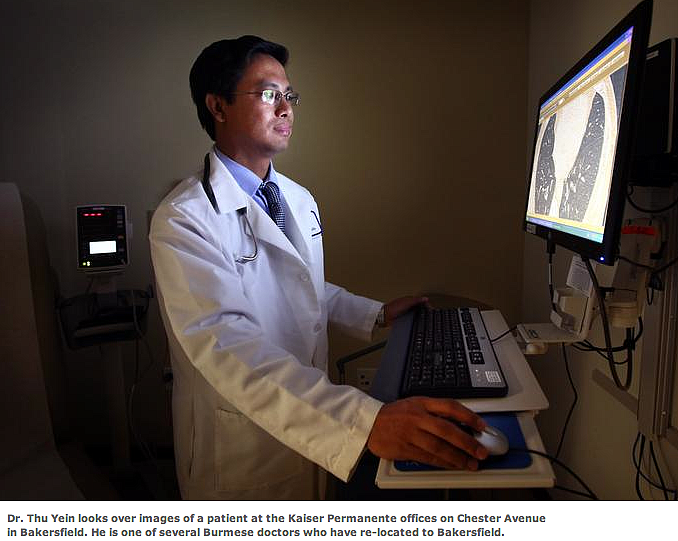

"We support each other," said Dr. Thu Yein, a Kaiser pulmonologist and the second in that chain of recruitment. "Knowing your friend is here improves your comfort level."

Yein decided to come to the United States because he wanted more training as a specialist.

"I wanted to be somewhere where I could learn more," he said. "As you can imagine, the whole world wants to be in a U.S. program -- that's the dream."

Upon arrival, he had to quickly learn certain customs and cultural differences -- such as how to approach Jehovah's Witnesses, or the role of "Do Not Resuscitate."

Yein also researched bedside manners and learned that patient confidentiality must extend even to the immediate family. In Burma, it's more common to discuss a patient's illness with the family present.

He remembers Burmese patients as simple people who are generally happy with life. When he practiced there nearly 20 years ago, malpractice wasn't a big concern.

While American patients may immediately notice he's foreign-born, he hopes what resonates more is his demeanor, he said, adding: "I always treat people like my family."

He still misses Burma, where his mother and father live, and laments the exodus of professionals like himself. With the political climate changing there, he's considered going back, though only for a volunteer stint.

Yein is certain he made the right choice settling in Kern County.

"People look at me as a good physician no matter what my skin color," Yein said.

Similarly, his brother-in-law Dr. Kyaw Tun said he's encountered less skepticism than he found in Oklahoma, where he worked just prior to coming here.

"Where are you from?' they'd ask," he recalled. "Why are you here? "

After he proved himself, that doubt cleared. But, he likes working with a population that is more accepting of foreign-trained doctors from the onset.

Like Yein, he still thinks of Burma and the brain drain that has robbed the country of its physicians. His smart friends still in the country are opting for business jobs since medical work doesn't pay enough.

"I'm glad I made this choice," he said. "A lot of people want to come, but it's difficult. The U.S. has the best education in the world."

This article was originally published by The Bakersfield Californian.