Killing Fields' Legacy

Nearly 40 years later, Cambodian refugees who can bear telling their stories recall atrocities in vivid detail, with an immediacy that is palpable. The effects on the lives of the refugees and their families have been profound and touch every aspect - their mental and physical health, their economic stability and their assimilation into the United States and the local community.

This article is part of a six-part series that looks at the effects of PTSD on members of the Cambodian community:

Part 1: Killing Fields Legacy

Part 2: PTSD from Cambodia's Killing fields affects kids who were never there

Part 3: At 92, she's still haunted by Khmer Rouge atrocities in Cambodia

Part 4: SAM KEO: Soul-searching helps win battle in mind

Part 5: ROTH PRUM: Genocide's horrors still haunt dreams

Part 6: ARUN VA: Narrow escape from becoming a killer

LONG BEACH - The pain stitches across the face of 91-year-old Sath Um as she recalls the horrors she witnessed and her brushes with death.

Roth Prum fingers the leaves of a small plant she holds as she talks about how "I became the cow" when relating her work pulling a plow through rice fields.

Arun Va says his memory is burned with the faces of five women he watched have their throats slit and bodies weighed down with rocks and sunk near the Tonle Sap lake.

"That one thing is in my eye all the time," Va says.

For years, Sam Keo was wracked by survivor guilt and shame for not sharing food with a sibling who died from starvation.

"I would wake up every night sweating," Keo says.

If one walks through the Cambodia Town area of Long Beach and spots an elder, the chances are they have similar stories. They have witnessed and were subjected to horrors that are incomprehensible to most Americans.

Throughout Long Beach and the United States, nearly 40 years later, Cambodian refugees who can bear telling their stories recall atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge, by their neighbors, by themselves in vivid detail, with an immediacy that is palpable.

It has been 37 years since the rise to power of Pol-Pot on April 17, 1975, but for those who lived through those times it might as well have been yesterday.

For them the genocide that wiped out about two million of their countrymen is always present. It may fade from time to time. It may be supplanted for a while by more immediate needs, medications, activities and work. But it is always there on the fringes.

That's what post-traumatic stress disorder does; it lurks and can return in an instant.

"For some people, the experience stays forever," says Keo, a licensed clinical psychologist with the Los Angeles Department of Mental Health.

The effects on the lives of the refugees and their families have been profound and touch every aspect - their mental and physical health, their economic stability and their assimilation into the United States and the local community. It colors relationships with their children and spouses.

Survivors may face a host of issues but "PTSD amplifies them," says Suely Ngouy, a policy advocate at the Asian Pacific American Legal Center.

Research shows PTSD may be linked to increases in health concerns such as diabetes and heart disease that are beginning to kill off the survivors at an alarming rate.

Children of survivors and those born in camps who are too young to remember the horrors also suffer. They have high rates of depression and anxiety and feel the weight of their heritage and racism.

Paline Soth, of Killing Fields Memorial Inc. in Long Beach, says "the one thing all Cambodians share is shame."

Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge were directly responsible for staggering atrocities in their short, brutal reign between 1975 and 1978, but their terrible legacy stretches to this day and lives on locked in the minds, souls and hearts of a generation for whom the scars remain.

What is PTSD?

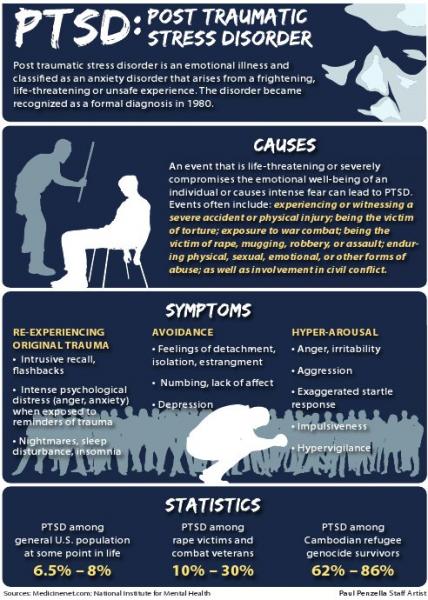

Although post-traumatic stress disorder has been around since the early stages of man and conflict, the term emerged after the Vietnam War in the 1970s and it was officially recognized in 1980. As such, understanding PTSD as a unique reactive disorder is relatively new, and debate and research are ongoing as scientists grapple to understand and treat the elusive malady.

Generally PTSD is an anxiety disorder that can be suffered after a traumatic event. The symptoms cross a wide array of emotions and intensities. It can cause physiological and biochemical changes to the brain and its functioning, along with the body.

Those who suffer from PTSD often relive the traumatic events, and the onset can be caused by something as simple as a loud noise or mention of a name, like the Khmer Rouge. These are commonly referred to as triggers.

The onset of PTSD can occur shortly after an event or be dormant for decades. It can pass quickly or last the rest of one's life.

There is growing evidence the fallout can lead to future health problems such as diabetes, heart disease and high blood pressure.

The disorder is generally treated with a variety of medications and various forms of interactive therapy.

There is ongoing debate about the effectiveness of Western psychotherapy as a tool in different cultures and whether it conflicts with alternative or culturally appropriate treatment.

Although research and money have gone into studying disease, particularly as it affects United States war veterans, full understanding of the disorder and its treatment are still in their nascent stages and remain elusive.

"Everyone copes differently," Keo says.

A community struggles

More than a generation after the genocide and refugees first came to the United States, the Cambodian community continues to struggle with poverty, education and overall health.

There are a number of reasons it has been slow to adapt and succeed in the United States. Almost all refugees were poor farmers with little or no formal education. The cruel joke at the time was they were illiterate in two languages.

"Many are struggling admirably," says Grant Marshall, who studied the Cambodian community for the RAND Corporation. "They were without the education to match the needs of employment. Many still struggle."

Parents often took on several low-paying jobs to feed their families and struggled to understand an utterly alien world.

"A lot went straight to the sweat shops," says Seng Kem, who grew up in Long Beach.

One of the Khmer Rouge goals was to wipe out those with education and Western training. Some estimate 90 percent of Cambodian doctors were killed.

In Long Beach, most refugees were located into already violent and poverty-riddled neighborhoods. Children were often abused in school by their classmates and many formed or joined Asian gangs that proliferated at the time.

"It was either fight or flight," says Kem, who was born in a refugee camp, but became a success story as a policeman. "I still run into (gang members) who are still active."

Against these overwhelming struggles, PTSD was often engulfed.

The Khmer population in the United States is about 277,000, according to the 2010 U.S. Census - a 34 percent growth since 2000. California has more than 102,000 Cambodians, 37,450 in Los Angeles County and about 20,000 in Long Beach.

A 2004 study by the Asian Pacific American Legal Center of Southern California highlighted the difficulties Cambodians in Los Angeles County face. The group is currently working on an updated report based on 2010 Census data.

The economic struggles of subsets of the Asian population are often masked by overall strong performance. In L.A. there are more than 45 Asian ethnic groups, speaking 28 languages. Cambodians, Hmong, Vietnamese and Laotians rank among the most disadvantaged.

The study found Cambodians had a 38 percent poverty rate, compared with 14 percent for Asians overall. Cambodians also had a low median age and large households.

On the positive side, this group recorded less linguistic isolation and larger rates of English language retention and naturalized citizenship rates.

About 39 percent received public assistance income, nearly twice the number of the next highest Asian ethnic group.

These last numbers seem to indicate that Cambodian social groups have done a better job of outreach to the community.

Making use of services

Despite the availability of services, for those who suffer the lingering effects of the genocide, the resources are all too often misguided or ineffective. Lack of cultural understanding, gaps in language and communication, and even differing world views and philosophies auger against meaningful treatment.

The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services diagnosed 1,157 Cambodians as being severely emotionally disturbed or severely mentally ill. In 2010, the county treated 964 Khmer patients.

"Certainly PTSD is one of the key diagnoses we come up with, and clinical depression is another," says Mariko Khan, executive director of Pacific Asian Counseling Services. "In the general population there are many who suffer."

Ngouy, of the Asian Pacific American Legal Center and a refugee herself, says PTSD is rarely diagnosed.

"It's hard," she says. "It's not something you get diagnosed when you get a physical."

Too often, she says, mental health takes a back seat to physical and preventative health issues.

Furthermore, with PTSD symptoms so common, many don't see it as unhealthy, Ngouy says.

"There hasn't been a lot of discourse about it," Ngouy says. "It become a back-burner issue when raising a family."

That's unfortunate, she says because "it's been a chronically urgent issue for a long time."

Keo estimates 90 percent of Cambodian refugees display PTSD symptoms, though not all are severe enough to be diagnosed with the disorder.

Several studies, including one in 2005 of Long Beach that Marshall conducted for RAND, show PTSD rates among Cambodian refugees at between 62percent and 86 percent.

Keo says most Cambodians go to treatment only when it is mandatory to receive disability and other benefits, or as part of a legal requirement.

In general Cambodians are compliant when sent for therapy, Keo says, but they often stop once the requirement is fulfilled.

"When they go they don't really get help," Keo says.

The only course to recovery, Keo says, is to commit oneself to the process, which he knows from firsthand experience can be long, hard and intense.

"The only way to do well is to cope with it and explore and find the triggers (of PTSD)," Keo says.

Most often Keo says patients are prescribed medication and sent on their way.

"Medications alone won't help without talk therapy," Keo says. "No one medication works for everyone. Those are like a Band-Aid to take when you're in turmoil."

When Keo first sought therapy after a return trip to Cambodia, he says two therapists told him he was doing well because he was successful and educated.

Keo was given medications, but it took rigorous psychotherapy before he was able to tame the demons and work full time.

Because he has a Western education and had a strong command of English, Keo was one of the lucky ones.

Treatment obstacles

Because of language and cultural barriers, most Cambodian patients have a hard time being engaged in their own care. About half need interpreters to help them understand their illnesses.

In a report on PTSD in refugee populations, James Knowles Rustad of the University of Vermont described some of the problems with cross-cultural treatment.

For example, Cambodians suffering PTSD symptoms might describe it as "thinking too much." That usually means they are suffering from anxiety and obsessive behavior, rather than thinking rationally.

Terms like "small heart" and "broken down heart-mind" refer to different aspects of progressive mental deterioration.

Also to Cambodians, mental illness is perceived as a family disease. Thus patients feel disconnected from Western services that don't emphasize the family.

Ngouy says Cambodian families will often try to shield and hide those in a family with mental disorders rather than expose the sufferers and themselves to scrutiny.

Keo says the perception is "If I'm crazy, the whole family is crazy."

Daryn Reicherter, a Stanford professor of psychiatry who works with survivor communities, says Cambodians are "among the most difficult to treat."

Studies of various traumatized groups showed Cambodians seem to be the most sensitive to negative stimuli.

In a podcast at the Stanford Medical School, Reicherter said the problem of "brokered language" goes both ways.

Translators often fall into a trap of "interpreting language into a symptom I can write down as PTSD," he says.

This, he said, can lead to a manufactured diagnosis.

Rustad says psychiatrists and counselors need to develop expertise in working with patients from specific cultures.

Among Cambodians that's problematic.

Keo says he only knows of two licensed Khmer therapists in Los Angeles, including himself, and neither works in a clinical setting. And while there are case workers who can interpret, he says much is lost in translation.

Translators need to be adept at explaining concepts between the cultures that may be completely baffling.

Physical disease

The affects of PTSD don't appear to be confined to mental health; it affects overall health as well. According to the National Cambodian American Health Initiative, Cambodians in Massachusetts are six times more likely than the overall population to die from diabetes, and in California, Cambodians are four times more likely to die from a stroke.

Health professionals are starting to take notice of the pending health crisis facing elder Cambodians.

In 2005 the National Cambodian American Health Initiative declared a state of health emergency for the Cambodian community. And in 2009 the White House launched an Asian health initiative to address the problem.

Reaching out

Since 1996, more than half of all Cambodian community- based social service organizations in the United States have been shuttered.

In Long Beach, Cambodians are lucky to have a variety of groups that can help.

The United Cambodian Community and Cambodian American Association have been the main social service organizations for Cambodians since the 1970s. Both operate on tight budgets, but offer numerous services to Cambodians young and old. St. Mary Medical Center has several health programs for Cambodians, and Pacific Asian Counseling Services has an office in Long Beach.

The Cambodian seniors nutritional program provides elders with fellowship and serves daily hot lunches, and Buddhist temples and Western churches have reached out to provide solace and spiritual healing.

Va, who works with the nutritional program, says Buddhism helped him find inner peace; Prum credits her conversion to the Mormon church in helping her quell the demons.

As Keo says, there is no one way to deal with the demons of PTSD.

Legacy lingers

Keo, accepting an award at a 2009 mental health summit, said: "When you meet a refugee, whether he or she is Cambodian, Vietnamese, Laos or Hmong, please remember that he or she may carry scars that are invisible, or wounds that have not yet healed."

"What's saddest is it's gone on for 30 years and it's still present," Ngouy says. Ngouy says there is a need for advocacy for PTSD treatment.

"We know unless the community is advocating you can't get it addressed," she says.

Sadly for many Cambodians, there will never be an end to the nightmares, the memories of torment and starvation. They will carry those to the grave, or the next life, and PTSD, depression and early deaths from physical disease will be the last lingering legacy of a terrible scourge.

But for many others, there will be healing and success.

Khan, of Pacific Asian Counseling Services, cautions that it's wrong to lump all Cambodians together as traumatized and nonfunctional.

"I had a very narrow idea of Cambodians when I first became involved," she continued. "There's actually a large number who are productive. I'm concerned that Cambodian population is pathologized and credit is not given to their resilience."