Minding the gaps

The series "Streetwise: Walking & Biking In Natomas" will examine whether efforts to create a healthy, walkable and bikeable community in Natomas have been successful.

Part 1: Building a better Natomas

Part 2: Safer routes for students

Part 3: Minding the gaps

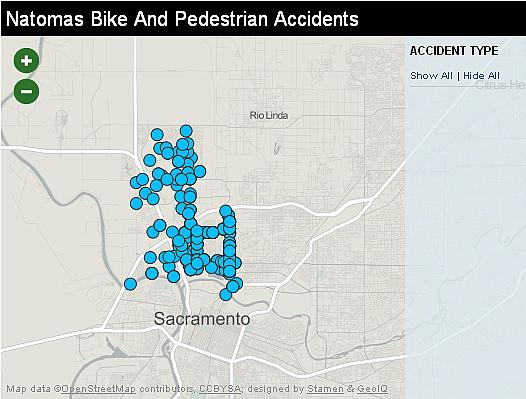

Natomas bike and pedestrian accidents

One of the most popular rides for bicyclists in Natomas could be one the region’s most dangerous.

Garden Highway is a winding, two-lane road which runs parallel to the two rivers that border the Natomas Basin. Here, the legal speed limit tops 45 mph.

“It’s a beautiful place, no doubt about it,” said Teri Burns, a Garden Highway resident for 15 years. “The problem is, really, that it is too narrow.”

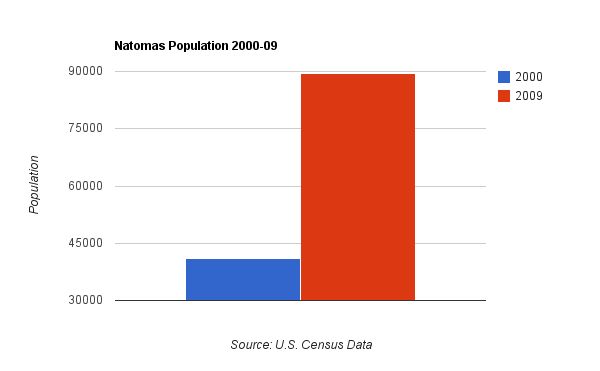

While the Natomas population has nearly doubled over the past 10 years, the number of those biking along Garden Highway has also increased and those cyclists who commute from Natomas to downtown must first cross, and then ride along a portion of, Garden Highway.

California Highway Patrol records show 15 bike versus vehicle accidents on Garden Highway between 2000 and 2010. (Six pedestrians were hit by cars along the same stretch of road during that period.)

Efforts to improve relations between Garden Highway residents and cyclists over the years have proven temporary, at best. A proposed fix that would pave the adjacent river levee could relieve tension between the two groups, and also benefit pedestrians, but lacks funding.

“Garden Highway doesn’t meet county standards for road width,” said Burns. “In places, there is no shoulder at all.”

DANGEROUS BY DESIGN

Elsewhere in Natomas it’s the wider, multi-lane streets that can create a hazard for those who walk and bike.

According to north-area police Capt. James Maccoun arterial roadways are designed to move people faster and have higher speed limits. Wider streets take longer to cross by foot, exposing pedestrians - and cyclists - to higher safety risks, he said.

CHP data shows higher concentrations of bike and pedestrian accidents with motor vehicles at intersections and along multi-lane streets in Natomas such as Truxel Road, Northgate Boulevard, San Juan Road and West El Camino Avenue. Over the past 10 years, more accidents were reported between cars and cyclists than between cars and pedestrians.

According to Dangerous by Design, a report published earlier this year by Transportation for America about an “epidemic” of pedestrian fatalities nationwide, Sacramento ranks as the eighth most dangerous city for walking in California and No. 22 in the United States.

Sacramento police Lt. Gina Haynes was so troubled by the number of pedestrian and cyclist fatalities citywide, she launched pedestrian awareness and ride safe bicycle campaigns last year.

“I was looking at the stats - 24 fatals last year and we had five bike fatals,” said Haynes, who oversees the police department’s traffic and air operations. “I had never heard of having that many before.”

Police implemented pedestrian “stings” where drivers were cited for failing to yield to those on foot. Rules of the road - such as wearing helmets and riding the right direction in bike lanes - were also enforced for cyclists.

“My whole thing is to stop fatalities,” Haynes said. “If I can prevent somebody dying, I will do it.”

In February 2004, officials amended the city General Plan to include “Pedestrian Friendly Street Standards.” The goal: to encourage more walking and cycling.

Two years later, in September 2006, the city adopted a Pedestrian Master Plan meant to improve walking conditions and create a “walking capital.” In turn, city dwellers could reap health benefits, encounter less traffic, help improve air quality and save money by not driving.

According to traffic engineer Hector Barron, the city works to install traffic controls when a neighborhood is built.

“Sometimes, because development does not all happen at once, you see improvements over time,” he said.

When residents report traffic concerns, he said, the city investigates. A city-run traffic calming program empowers residents to help identify measures to slow vehicles, making streets safer and more attractive to pedestrians.

To date, several traffic calming projects - including one Laurence Wilson volunteered for in 2008 - have been completed in Natomas.

“When we first moved in, motorists were using Banfield Drive like a race track,” said Wilson. “When the school opened … not a whole lot changed. During the day people were driving pretty fast and at night, really fast.”

The traffic calming plan Wilson helped work on focused on residential streets surrounding Heron School, located across the street from his house. By project’s end, speed humps, marked crosswalks, pedestrian islands and other measures had been added to streets around the K-8 campus.

According to Wilson, results have been mixed. Drivers have slowed, he said, but rarely stop at the intersection where signs were added.

NOT ACCORDING TO PLAN

Planning for bicycles and pedestrians played a significant role in building out the Natomas community, Barron said.

“It is probably one of the largest efforts of the city of Sacramento to try to make it a multi-modal area,” he said. “It is the only area in Sacramento where transit is planned out.

Multi-modal communities have more than one method of transportation available. Generally, the term refers to the walking, biking and the use of public transportation such as buses in addition to driving motorized vehicles.

Key features in the South Natomas Community Plan included several bike- and pedestrian-friendly parkways and a proposed light rail line that would connect walkers and cyclists in south Natomas to the central city and as far north as the Sacramento International Airport. The North Natomas Community Plan envisioned smaller commercial centers within walking and biking distance of homes; larger shopping areas were to be accessible by bus and the proposed light rail line.

Pedestrians use the popular Bannon Creek Parkway

Budget cuts to public transportation have resulted in limited bus service throughout Natomas. Lack of funds have also delayed building the light rail line from downtown Sacramento to the airport by several years; the project has been pushed back - twice - from 2015 to 2021. Even the local school district only buses middle schoolers who live south of Interstate 80 and special needs students.

“The plan looked pretty good on paper, but when it came down to building, that’s where things diverged quite a bit,” said Chris Holm, a project analyst for Walk Sacramento, a nonprofit community group working to create walkable communities throughout the city.

The North Natomas Community Plan was changed and lost neighborhood commercial areas, building was sporadic and spaced out throughout the area, the road system changed and planned schools disappeared altogether, according to Holm.

“The vision was good,” he said. “It’s not horrible, it’s just not quite (as walkable) as we would have expected.

CONNECTIVITY IS THE KEY

Connectivity refers to the street and pedestrian network.

“A well-connected network of streets and pedestrian ways means that it is easy for the pedestrian to get around,” reads the Sacramento Pedestrian Master Plan. “Connectivity includes support for safe, convenient street crossings.”

In Natomas, the lack of connectivity is an obstacle from being a truly walkable and bikeable community for residents like Karen Quant.

“Coming from a city where all I did was walk or hop on public transit, I liked the idea (of a master planned community),” said Quant, who moved to Natomas eight years ago from San Francisco. “It just sounded like it was going to be easier to access … it’s not how I imagined.”

Quant uses the walkways atop neighborhood canals when the weather is nice, but had envisioned a community where she could walk to places and get things - errands - done, too.

“I wanted to have a community where walking was a way of life and not as much an event,” she said.

Former city councilman and longtime Natomas resident Ray Tretheway said the region has more off-street and on-street bike paths than anyplace else in Sacramento. But incomplete bikeways and missing links between trails are confusing to cyclists, he said.

“The biggest challenge is connectivity,” Tretheway said. “We have a long ways to go, many decades, to finish the bicycle dream of Natomas.

The new bike and pedestrian bridge over Interstate 80 opened earlier this month is a first step toward connecting trails north of the freeway to those on the south, but the status of two more, long-planned bridges - one over the freeway at Truxel Road and another closer to Northgate Boulevard - is unknown.

City councilman Steve Cohn, a new representative for south Natomas neighborhoods as a result of redistricting, has pledged to review both the 2003 Gardenland-Northgate Strategic Neighborhood Action Plan and 2006 Northgate Boulevard Streetscape Plan. Both plans tackle pedestrian safety issues, however, funding a multi-million dollar project along the well-traveled corridor might prove to be a challenge.

Said Holm of Walk Sacramento, “It’s going to be tough and it’s going to take creative people within the city to probably grasp fewer and fewer funding opportunities.”

For the nonprofit North Natomas Transportation Management Association working with the city on connectivity fixes including curb cuts, resurfacing north-area bike paths and finishing others has been a priority.

“We want to see North Natomas known as a good biking and walking community,” executive director Becky Heieck said. “We want people to come off the freeway and realize they have reached a place where people ride and walk.”