Northside: Story of the mill village is a familiar one

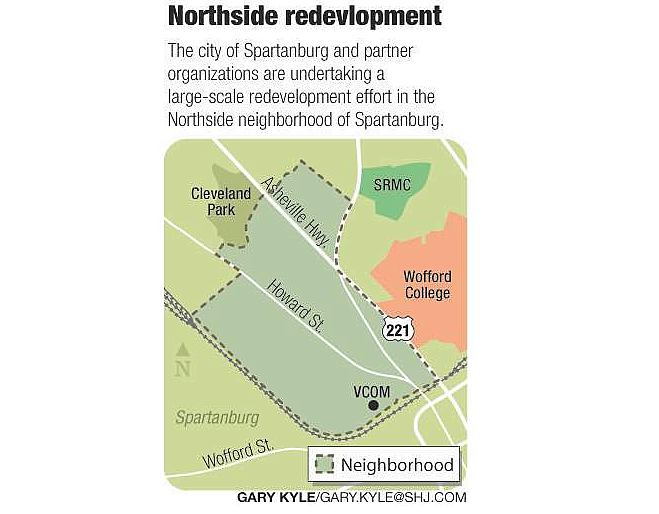

Spartanburg, S.C., began as a bustling mill town, but parts of the city went downhill after drug dealers infiltrated some neighborhoods. Now the rebirth of the Northside is creating an opportunity for new life.

Andrew Doughman wrote this series of articles for the Spartanburg Herald-Journal as a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. Other stories in the series include:

Northside: Being transformed into a healthy and thriving community

Northside: Single mom looks for college and a good job

Northside: Neighborhood's future depends on healthy choices

Northside: City is following Atlanta redevelopment plan

Spartanburg County Council considers fee-in-lieu of tax requests

Northside: Cleveland Elementary plays part in redevelopment

The story of the Northside is familiar to longtime residents of Spartanburg County. It was at first a mill village next to Spartan Mill — at the time Spartanburg County's largest mill — and then a rail hub and a destination neighborhood for the captains of industry who built the economy during the earlier half of the 20th century.

The Cleveland family owned wide swathes of the neighborhood. They donated the land for the current Magnolia Cemetery and Cleveland Academy of Leadership, which is within walking distance of the county's premier park: Cleveland Park. The park even boasted a zoo in the 1920s.

In many respects, the neighborhood was at the center of the action in the county.

The neighborhood, at times alternatively called Spartan Heights or Cleveland Heights, housed professionals who lived along clean, tree-lined streets not a mile from the county courthouse and across the highway from Wofford College and the hospital.

The neighborhood hosted — and still hosts — the annual Piedmont Interstate Fair. Theatrical performances in the Montgomery building downtown were a short ride away. Neighbors who wanted to see the Charles Lindbergh parade through Spartanburg in 1927 would have been minutes away from the celebration.

Dr. J.F. Cleveland kept a home at the site of the elementary school, which the Clevelands donated for the purpose of building a school in 1938.

That event marked the beginning of the Cleveland family's slow divestment from the neighborhood during the 1940s. The earlier generation of patriarchs had died, and the children sold their parents' land. In 1948, they sold several parcels to developers, who built the current Oakview Apartments.

In 1967, they sold parcels across the street to the Spartanburg Housing Authority, which built the current Victoria Gardens public housing project.

The Cleveland family's divestment was a precursor to a broader exodus in the late 1960s and 70s.

At the time, Spartanburg's state Sen. Grady Ballard lived in the neighborhood. The neighborhood was dotted with corner stores, bars, hardware stores and restaurants.

At Cleveland Park, the Red Cross used to teach white children to swim. Black people were barred from swimming.

"It wasn't a law. You just didn't get in," said Annie Tate Lynn, 64, who lives near Cleveland Park. "There was one day a black got in and all the whites got out."

Linda Dogan, the city councilwoman who represents the Northside, remembered playing in a field with other black children because Cleveland Park was segregated when she was young.

The pool was integrated in the late 1960s, and Dogan said she swam there for about a month before she showed up one day to discover not water but cement in the pool. The closing of the pool was a bellwether, foreshadowing a broader change for the neighborhood.

Linda Askari, who was one of the first black women on Leonard Street near Cleveland Park, saw a "for sale" sign sprout along the street the week she moved in.

Charlie Weaver, owner of Charlie's Used Cars on Howard Street, the main thoroughfare in the Northside, watched the neighborhood shift dramatically in the 1970s.

"Back at that time, one black family would move in and all the whites would move out," he said. "They may have lost money to go somewhere else they wanted out so bad."

The neighborhood shifted from a mixed-race neighborhood to a majority black one.

Katherine Lyles, 76, moved on North Vernon Street, not far from where Ballard had lived.

"I never thought I'd be on this street," she said.

Her husband had worked at Spartan Mill, and she had lived nearby on Aden Street during the 1950s and 60s.

Back then, up on North Vernon Street, neighbors would block off the street on the weekends, and the white kids would play games and sports and use adjacent Chapel Street Park, she said.

The only black people allowed in were gardeners in their yellow or orange jackets and maids who had black dresses who entered around the back of the houses, she said.

With those days gone, and white people moving to the suburbs, renters filtered into the neighborhood and lived far from the supervision of absentee landlords.

"Houses started changing, people started to die out, and renters came in," said Annie Martin, 72, who has lived in the same house in the Northside since 1948. "I guess the kids just didn't want to live over here."

It was about that time, in the 1970s, that the hard drugs appeared, Weaver said.

A downward spiral

Neighbors say a crop of longtime residents held on through the 1980s and 90s as drug dealers and other criminals overran Cleveland Park and prostitutes openly walked along Howard Street.

"There have been times people would tell me (prostitutes) tried to solicit them right on my lot," Weaver said.

Meanwhile, the shops were closing. The restaurant where Dogan said blacks could buy a hotdog but couldn't sit down to eat it is now an empty lot. The hardware store is closed. Weaver bought and closed the bars and clubs near his lot.

There's no longer any place to sit down and get a meal in the neighborhood. Even the Burger King closed.

All the while, the housing stock deteriorated.

Lyle's neighbor is an absentee landlord. The house has peeling paint. Pieces of the roof have blown into her yard.

"Nobody stays there a year," she said. "They move in and out. ...I just want people to clean it up."

Weaver was once a landlord. Sure it made money, but it was a tough business.

"They are kind of ran down," he said of the houses. "You get people in; they won't pay. They trash the place. I just got tired."

One woman kept dogs that she could not afford and did not care for.

The house was in such bad condition that he had to bulldoze it, he said.

Rebirth

Now, with revitalization talk abuzz, the Northside is gaining some cachet.

Nancy Riehle, a local realtor, recently purchased a row of houses near the Northwest Recreation Center.

"My goal is to make this the post card for Spartanburg," she said.

It hasn't been easy. She had a group of potential investors touring the houses, and as they stood on a street corner, she said "a police car pulled up and these two guys ran up, and they started shooting at each other."

"That was the end of the sale," she said. "I thought I was in a movie."

Spartanburg Public Safety Officer Chris Taylor, whose office is in the Northwest Recreation Center, said that's a rare occurrence.

"You had a bad day," he told Riehle.

But now she's made the sale, and she's lining up potential buyers.

"We have a lot of single, working moms interested in three-bedroom houses, a couple of veterans. They're all families," she said. "There's a demand."

Several weeks ago, Riehle filed a report with Spartanburg Public Safety. She told the police two of the still-vacant homes were burglarized and the copper wiring was stripped out.

This story was originally published at GoUpstate.com on January 26, 2013

Photo Credit: GARY KYLE