Pamela Tapia: My life as an asthmatic

In high school, Pamela Tapia spent more time at home with her inhaler than at school with her teachers. Now that she has moved just a few miles away from the poor air quality in West Oakland, for the first time in four years, she celebrated an asthma-free birthday.

Staff writer Katy Murphy and photographer Alison Yin produced this project for The Oakland Tribune as part of a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellowship. Other parts to this series are:

By Pamela Tapia

When I came to Oakland from Mexico in 7th grade, language was not my greatest challenge. My immigration status was not a barrier either. Asthma was my nemesis.

My first attack was on my way to McClymonds High School, when I was a shy sophomore being bullied at school and a newcomer barely treading water socially.

I'm not going to say that I felt scared when I had my first asthma attack. I wasn't.

I will say this: It bears no resemblance to the words on the huge cheery billboard in the heart of West Oakland that pronounces: Asthma is "feeling like a fish out of water." It's more than that. Way more.

Asthma is frustration, a child rebelling against his parents, throwing a fit desperate to be noticed.

When I was 3, my mother sent my sister and me to live in the rural Mexican pueblo of Acambaro, Guanajuato, under the guardianship of my grandparents who lived in a secluded ranch away from the big city, where the only transportation available was walking or on horseback.

Growing up, I was a normal kid -- I climbed on things that weren't meant to be climbed, swinged on ropes into the crisp water of the river that flowed nearby, played soccer and basketball on my school's teams. During my physical education class, I noticed I wasn't the fastest and seemed to always be the one frantically catching my breath after every mile test. Even though breathing was meant to be an automatic process, somehow, it became labored.

Here's the thing: Asthmatic lungs are the greediest things in the world. With every inhale, there can't seem to be enough air in the world and you wish that they would just stop breathing but they keep clawing at your throat gasping for air.

When I returned to the United States, my family moved in an apartment in West Oakland. I was obligated to see a doctor for the physical and immunization shots when enrolling for my first year in an American school. I was spared my first attack for three years, as we moved from place to place, to East Oakland, Manteca and then back to West Oakland, which has poor air quality.

My first asthma attack was not a gradual process, it was a detonation, everything at once shutting down but just not fast enough.

My muscles would not allow me to sit up without my lungs whining. My fingernails turned blue, dark spots appeared in my vision, my knees turned to sticks crumbling underneath the weight of my body, but my head remained incredibly light.

I got ready for school and started to walk toward the bus stop. After climbing down my front porch steps, I could not keep going, asthma did not let me. Asthma is the first enemy I knew, the one who had actual control over me, the one that could end my life without remorse, but lives and is part of my body. However, the constant threat of asphyxiation, drowning, or strangulation (take your pick) was getting old.

When I first arrived at the emergency room, I mimicked a 4 year old, pointing at my throat and my lungs, not being able to construct sounds into words. I was approached by a nurse who handed me a clipboard with smiley faces at the end of a continuum labeled "No Hurt" to "Hurts Worst" that stood at opposite ends.

At that moment that was all the pain that I felt.

All I knew is that I couldn't breathe and I couldn't let myself think about anything that didn't involve getting air through my lungs. Maybe, just this time asthma had won.

I was placed on a seven hour oxygen treatment that involved my being plugged into a machine that produced vapor from eucalyptus extract mixed with oxygen. My mom was told that I needed to be kept in the hospital for two weeks to monitor my progress. One can only watch so many SpongeBob episodes without going completely mad, so I asked my mom to bring my laptop into my hospital room so I could continue working on my article for the Oaktown Teen Times, which ironically was about poor air quality in West Oakland.

Four students from Mack (formerly EXCEL High School) traveled to Diamond Bar (about 30 miles east of downtown Los Angeles) on Sept. 25, 2010, to testify before the state Air Resources Board about the health effects of diesel pollution caused by rail yards in West Oakland. The students appeared before the board to give a personal perspective to research on how bad air affects students in urban schools.

During my first months at McClymonds, I had thrown myself into an environmental justice project, tracking pollution, reading studies and testifying before the California Air Resources Board. Pollution is a community problem in West Oakland but, at that point, it was all theoretical to me. I was still an activist, not a victim. That quickly changed.

During an asthma attack, the muscles surrounding the airways tighten limiting air flow as the airway walls become inflamed. The only reason I know this is because of the

In my four years in West Oakland, I was hospitalized on three different occasions for several weeks at a time. Every year, around my birthday, I would go see a doctor because I couldn't handle not being able to breathe anymore and the medicine I was placed on was not doing its job. I would be hospitalized for two or three weeks. Happy birthday, now die.

In the periods in between anniversary hospitalizations, I was told to connect to a nebulizer every three hours for two-hour oxygen treatment. I couldn't exactly carry around a bulky, loud breathing machine and plug it in during Geometry class or walk down the hallway with a cannula hanging from my nostrils.

It was bad enough just carrying around an emergency inhaler, not that it didn't work. It was the fact that every time dope-sniffing dogs were brought in to check for stoners in the classrooms, I was the one who was brought into the principal's office to empty the contents of my pockets and backpack as security officers checked my locker. I had the accessory a girl cannot go without: an inhaler. At least it's small and red.

Needless to say, I missed a lot of school. I spent more time at home with my inhaler than at school with my teachers.

It frustrated me academically, because even though I was keeping up with my reading assignments, I was losing attendance and "participation points" with my teachers; there was no policy in place then to allow me to make up assignments and tests due to my asthma hospitalization. I got an F in English, my best and favorite subject. I barely passed Spanish (in which I'm not only fluent but had mastered the grammar). History -- another subject I liked -- was not much kinder.

Just as I was losing the battle for breath, my insidious asthma was also putting me in a position to fail at McClymonds, a school at which I was new, one of a handful of Latinos, and too shy to speak up. I managed to maintain a 2.0 GPA, which was low for someone who passed the CAHSEE (California High School Exit Exam) on the first attempt. Plus, my SATs were more of an indication of my potential, I hoped. Although my grades improved, to a 3.7 my senior year, as I adjusted to the illness and began loudly advocating for myself, my GPA was still below what I needed to gain admission to a CSU or a UC. I enrolled in community college, and plan to transfer to a UC.

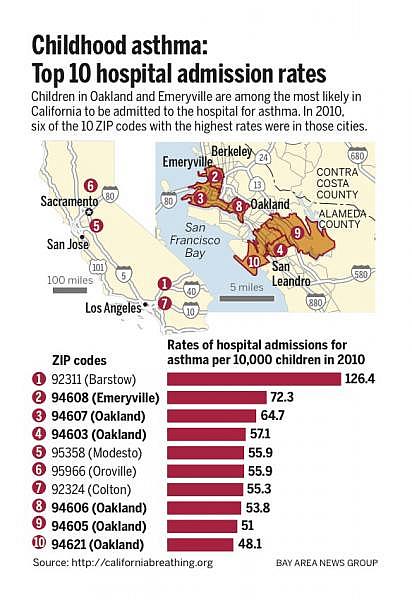

When my family was evicted from our apartment on the Oakland/Emeryville border (after my Mom lost her factory job) last year, I moved in with an ex-teacher in the Oakland-Berkeley hills, just 4 miles away. This year, for the first time in four years, I celebrated an asthma-free birthday. In the hills, just 4 miles from the diesel fumes and confluence of highways that makes West Oakland so polluted. I can finally breathe.

This story was originally published in the Oakland Tribune on February 9, 2013

Photo Credit: Pamela Tapia