Part 2: 'Willful blindness:' After Harvey, a Victoria family feels forgotten

This article was produced as a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Christmas miracle arrives for family struggling to rebuild after Harvey

PART 4: Will small towns recover after Harvey? It's a matter of if, not when

11 years have passed since affordable housing was built in Victoria; advocates say change needed

Part 3: Mold, bedbugs, rising rents — the reality of renting post-Harvey

Volunteers help Vietnam veteran living in car after Harvey

More than one year after Harvey, Vietnam veteran still living in his car

Hurricane Harvey exposed the gap between people who could afford to rebuild — and everyone else

Rebuilding after Harvey: 'You have to build their lives — not just their homes'

Reporter column: We listened to your stories about life after Harvey. Now it's your turn to act.

'We just got so much work to do': Number of homeless outside of shelters triples in Victoria

In a Victoria motel parking lot, Zoey Bowman sits on the ground and pouts in front of her mother's minivan in September. The 5-year-old was told she could not bring a lightsaber toy into her family's rented room because an ill-tempered brother would use it to instigate a fight.

Angela Piazza | apiazza@vicad.com

Although dozens of cars whiz past her every day, sometimes Devan Orsak believes the people around her pretend she doesn’t exist.

It’s 1:07 p.m. In 2½ hours, she must pick up her children. She stares at the oncoming cars, hoping to catch the eye of someone who might spare a few dollars. Most drivers look straight ahead, avoiding eye contact. Some roll up their windows.

The mother knows many drivers are judging her. Sometimes, tears pool in her bright blue eyes when she thinks about it. Those tears start to flow down her cheeks when she thinks about her children and how they haven’t slept in the same place for more than five days in almost two months. “I can’t afford to stop,” she said, “because if I do, my kids won’t have a place to sleep.”

There is no single cause to blame. Her situation is instead the consequence of a complicated mix of evictions, rising housing costs and poverty. Then, Harvey struck. In the year that followed, Orsak and her seven children were eventually left without a place to sleep, cook meals and call home.

But for both the passing drivers and the residents beyond where the mother holds a sign, it can be easier to ignore Orsak – and the complex economic and social inequalities that she represents.

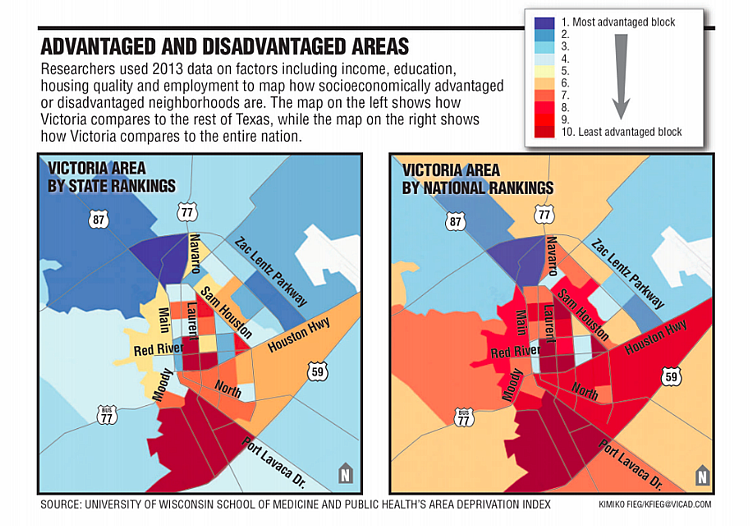

Before Hurricane Harvey, Victoria’s rich and poor lived in different realities. But besides wreaking havoc on homes and businesses, the storm further exposed vast disconnect between some of Victoria’s governmental leaders and their most vulnerable constituents.

A driver stopped at a red light ignores Devan Orsak, 37, who holds a sign that says “Need Gas.” Orsak said drivers often ignore, stop far away, roll up windows and, on one occasion, throw food at her. Even though she and her seven children are no longer homeless, Orsak says she must continue to panhandle to pay for food, gas and other basic needs for her family until she finds a steady job. (Photo: Angela Piazza)

During the past year, communities across the nation like Monroe County, Fla., and La Grange jumped to create housing for residents who couldn’t afford to rebuild after natural disasters. But in Victoria, there have since been few public discussions on a local government level about how to pave the way for the construction of new rental units or how to help residents like Orsak, who was struggling to find stability well before the hurricane.

Instead, immediately after Harvey, some officials questioned the extent of the hurricane’s damage. During a meeting two months after Harvey, for example, the mayor told other councilmembers that he’d heard a story about students living in cars. “I said, ‘You send that first student in a car to my house because I got a place to put them,’” said Mayor Paul Polasek. “No one has taken me up on that, so there’s a lot of information that gets embellished.” By spring, however, more than 1,900 children in Victoria qualified for programs to help homeless or displaced students under the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act – more than double the year prior.

Similarly, a couple weeks after that meeting, another City Council member stood up to clarify that it wasn’t the city’s job to provide housing. Her comments came only a few weeks after nonprofit leaders stood at the lectern in the council chambers, pleading with the City Council to address a lack of temporary housingthey feared would leave people homeless.

The Victoria Advocate contacted all seven members of the City Council, but only three responded. All three agreed that the city wasn’t responsible for providing housing or spurring development, but should reduce barriers by limiting costs of building codes, permits and taxes.

The mayor said the city has undertaken efforts in the past to support groups that provide affordable housing and that current level of involvement is “satisfactory.” When it comes to tackling poverty, the private sector is better suited, he said.

Meanwhile, Councilman Jeff Bauknight said it’s not the city’s function to boost housing, but he understands that housing prices across Texas have started rising beyond what some residents can afford. Instead, Bauknight said, he’s focused on raising wages so families can afford homes – by boosting the number of high-paying jobs and increasing trade programs for youth.

Councilwoman Jan Scott echoed their sentiments, adding that the city shouldn’t take the lead in solving often “emotional” problems. “I don’t think the city or its officials, as individuals, have any more responsibility to address this problem than any other person you interview or that is reading this article,” she said. “We must all do what we can to aid those in poverty.”

But one expert who has studied race, power and class in Victoria said the council’s sentiment is a long-standing one. “It is willful blindness: ‘I don’t see it. It must not be there,’” said Anthony Quiroz, who grew up in Victoria and now works as a professor at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi. “That is how people live.”

This attitude, experts warn, has prevented the community from tackling systemic problems that have plagued the city in one form or another for decades – ranging from racial inequality to homelessness to a lack of high-wage jobs.

In the late 1970s, for example, a federal program was going to provide summer activities for children born into poverty, Quiroz said. The program would have paid for those kids, who were mostly Hispanic and black, to participate in summer activities. It didn’t cost a dime of local taxpayer money, but the City Council had to approve it.

That didn’t happen.

“They thought it was sending the wrong message – that you could get something for nothing,” Quiroz said. “And these kids need to learn that they have to work hard to deserve anything.”

It’s been decades since then, Quiroz said, but the same mentality persists among some Victoria residents. And in Harvey’s aftermath, it could leave residents like Orsak and her seven children even worse off than before.

No matter whom Orsak asks, it seems as if the answer is always, “No.”

Wearing a faded black T-shirt and athletic shorts, she’s scrolling through Craigslist ads on a public computer in a hotel lobby, calling landlords to see whether they could accommodate her seven children. “I just can’t find a house,” she said, nervously tapping her pen on a hotel room notepad. “I keep getting turned down.”

After Hurricane Harvey forced hundreds of tenants out of Victoria apartments, finding an affordable rental home can be difficult even for people with decent credit, favorable rental histories and no children. But for Orsak, it seems virtually impossible. First, she has to find a home under her monthly budget of $950. If she finds one, she then must explain to landlords that she has seven kids. Then, she has to tell them about her past rental history and evictions. Last but not least, she prays to God that they’ll rent to her anyway.

Zoey looks at Halloween decorations through the window of Dollar Tree while her mother and sister attempt to collect enough donation money to rent a motel room for the night. (Photo: Angela Piazza)

But Orsak already knows how it feels when life kicks you down. She grew up 70 miles east of Victoria in the town of Bay City, where her parents divorced when she was young – an event she said was largely triggered by her mom’s mental health problems. Eventually, her mom moved to Kansas, and Orsak and her siblings followed. That didn’t end well: Orsak said she bounced between youth homes, foster families and then back to family in Texas. During that time, there was one thing in her life that remained constant – her battle with anxiety and depression.

“If you say anybody falls under the statistics, I think I fall under it, right?” Orsak asked, referring to studies that children in foster care are more likely to end up homeless, deal with mental health issues and abuse drugs or alcohol. “I just haven’t made it to prison yet.”

Until recently, though, Orsak got by. After her first husband died more than a decade ago, she was able to support her children by working odd jobs and relying on his Social Security sent for her children. Her life was often stressful – occasionally Child Protective Services got involved – but she was always able to get it resolved.

Then Hurricane Harvey struck, damaging her rental home. The landlord made repairs, but Orsak said that mold and mildew started to grow. She wanted to withhold rent, but in Texas, that’s generally not allowed. In early 2018, she was evicted. With financial assistance from a local nonprofit, the mother soon found another home to rent. But after the assistance ran out, she fell behind on rent. Over the summer, she was evicted again.

Now, the money she gets from Social Security and generous strangers is almost entirely spent on nightly motel rooms, which cost up to $85 a night. Being homeless is expensive: Her family spends more on food, drinking water, gas, laundry and clothes, too. And since Orsak is often strapped to quickly find cash to pay for motel rooms, she hasn’t had the days off needed to apply for a job.

In a way, it seems like poverty, and the problems that come with it, are infectious. Once one string starts to come loose, the fabric of life unravels.

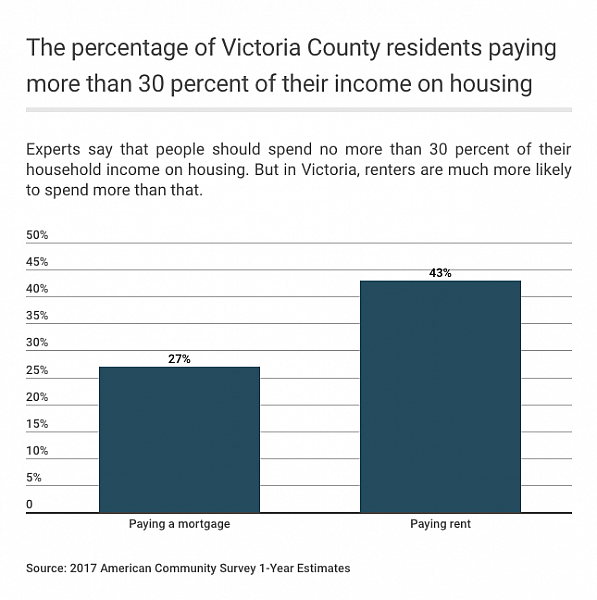

Although Texas frequently ranks among the nation’s cheapest states to live, Victoria’s low-wage renters sometimes found themselves competing with out-of-town oil field workers for housing years before Harvey struck. In recent years, almost half of all renters were considered “rent burdened,” which means they spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, according to census estimates. Yet despite those trends, local government leaders made limited attempts to address those problems.

It wasn’t always that way. In the early 2000s, for example, the city’s long-term plan said there was a lack of affordable rental housing and identified a “(resistance) to change” as an obstacle to success. Back then, the city also routinely spent the vast majority – up to 75 percent – of a federal grant aimed at improving communities on housing programs. Although most of that money benefited homeowners rather than renters, it paid for programs ranging from rehabilitating aging houses to buying land to give to Habitat for Humanity to develop.

But that changed. About a decade ago, officials slashed the amount of federal grant money it earmarked for housing programs. Meanwhile, some officials also pushed back on efforts to build more affordable apartments – in 2012, a housing developer came to the City Council asking to build new units, but officials’ limited support essentially killed the project.

Officials also stopped funding other housing programs, including the program that fixed homes in need of repair. Since then, the amount of federal grant money earmarked for affordable housing never recovered to previous levels. In the past two years, the city allocated no more than 3.4 percent annually.

The city, however, said it has not shifted focus away from housing. Since 2000, the amount of federal money given to Victoria shrank from roughly $1 million to $550,000 annually. During that time, construction costs rose, making programs like rehabilitating aging homes inefficient, according to a city official. The feds also stopped the city from saving the money year over year, which prevented Victoria from collecting large sums of funding needed to help pay for big projects, such as an affordable subdivision.

Instead, the city targeted federal funding on community projects ranging from rebuilding a homeless shelter for men to renovating the Boys & Girls Club to upgrading parks and sidewalks in areas where families with lower incomes live. And when Harvey struck, the city sought multiple grants to help homeowners with lower incomes repair houses.

“We decided to focus our limited (federal) funds on projects and activities that would have broader impacts on the community,” said John Kaminski, the assistant city manager.

At least in all her struggles, Orsak has become resourceful. She knows how to make money stretch and turn a few dollars into a hotel stay, a meal for her seven children, a car insurance payment or phone bill.

Earlier in the day, she got $27 while holding a sign. Then she took $8 of that cash to buy neon-colored crosses and rainbow-colored string at a craft store, which can be fashioned into necklaces that she gives to strangers when she asks for help.

She usually prides herself on her ability to crack witty jokes in bad situations, but it’s 5:16 p.m., and she doesn’t know where her family will sleep tonight. She parks her minivan at a Victoria strip mall, then herds the children toward the entrance of Dollar Tree. This is a common routine after school gets out. They sit cross-legged on the pavement, stringing together necklaces as shoppers walk in and out of the store.

And so it begins, the delicate balance of juggling antsy children and scraping up cash for a motel. While holding the hand of her 5-year-old daughter, Zoey, she asks shoppers if they would spare a couple dollars. After three “nos” in a row, Orsak sighs, and Zoey starts tugging on her mother’s arm. “My hands are so full,” her mom said, talking about the crosses. But it seems like a metaphor for something more than just that.

Poverty, Orsak knows, can be passed down from parent to child. Almost all of her children are struggling in school. Her 8-year-old son sometimes threatens to hurt himself. If only, Orsak wonders, she could provide her children a stable home. If only, at the very minimum, there was an emergency shelter that accommodates both parents and their children – something that doesn’t exist in Victoria, a county where almost half of single mothers who have children under 18 live below the poverty line.

She tries not to dwell on that. But then, a woman who left the strip mall earlier drives back into the parking lot. She calls Orsak over to her window, and says that anyone, even her own daughter, could find themselves in that sad situation. She hands Orsak five $20 bills.

Orsak starts crying, wiping the tears from her cheeks. “Hey, let’s go get a room,” she tells her children.

A motel manager counts $84.75 for a room with two queen beds and a pullout. He was hesitant to rent to Orsak because he said the motel, located on the outskirts of town, was almost at capacity. After paying for the room, Orsak had $13 left to feed herself and seven kids. (Photo: Angela Piazza)

“Please don’t get a terrible one,” her 10-year old daughter pleads. Her 11-year-old, however, is more pragmatic: “Get a terrible one because it’s really cheap.”

“I ain’t gonna be selfish,” Orsak said. “God gave me what I need.”

More than one year after Harvey, there’s no way of knowing how many residents, like Orsak, found themselves in worse situations – both physically and financially – than before the storm.

In Harvey’s immediate aftermath, local officials didn’t jump to tally damage to homes and businesses – even though Victoria’s emergency plan said the city should create and train damage assessment teams. Instead, the city just did “windshield surveys” – basically, city staff drove around town to view the damage. Meanwhile, residents who were displaced by Harvey’s winds and rains found themselves without a long-term shelter – even though the same plan said local officials were also responsible for providing one.

It wasn’t until seven months after Harvey that a survey by the Victoria Advocate would find that about one-third of the city’s apartments were damaged, including 400 that were so bad that tenants were forced to move out. Later that year, Victoria’s school district reported that half of its teachers were temporarily displaced.

But during the past year, the topic of rental housing problems that Harvey caused gradually disappeared from local government meeting agendas. In the mayor’s state of the city address in July, he didn’t once mention housing issues after Harvey. It’s a phenomenon that experts say in part exemplifies how elected officials often have vastly different experiences than the people they represent.

“I can’t tell you the number of times I go to these recovery meetings and people will say, ‘Well if you drive through Houston, it looks fine,’” said Shannon Van Zandt, a professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University. “You’re not seeing so much of the human suffering that is happening.”

In the aftermath of disasters, research shows that it takes more than just traditional market forces to help some people rebuild, especially families who were barely juggling the costs of rent, utility bills, food, gas, medicine and child care in the first place, Van Zandt explained. Without outside support, whether from federal aid or nonprofits, housing for those families probably won’t be rebuilt because construction costs are more than their wages can afford.

But without stable housing, communities can’t expect people, like Orsak, to be productive members of society. “If people think about themselves, and if they had to sleep on the street or in their car, and they didn’t know where they were going to brush their teeth or even use the bathroom, the level of stress would be so great that they wouldn’t be able to function,” she said.

There’s a financial cost that comes with that, too. It’s an argument commonly found in efforts to combat homelessness: Preventative efforts, like providing safe housing, are often cheaper than law enforcement, legal and medical costs when things go wrong, Van Zandt said. In Victoria, for example, the county’s hospital spent $6.9 million providing charity care to people who couldn’t afford their bills in fiscal year 2017 – a 33 percent jump from the year before.

“In many cases, you can save the community a lot of money if you address the needs at the root and not the consequences later,” Van Zandt said.

Across the nation, communities have taken all sorts of approaches to solving those complicated problems. In Charlotte, N.C., community leaders created a task force that examined how to help children born to families with lower incomes move up the economic ladder. Meanwhile, in Bend, Ore., the city created a special committee to tackle housing problems and exempted some affordable rental projects from city taxes. And in the aftermath of hurricanes last year, communities such as La Grange and Monroe County, Fla., created land trusts to provide new homes for people who lost them.

But sometimes, it takes more than just providing housing, local advocates contend. It requires commitment from the community and leaders to boost access to supportive services such as financial education and mental health care – the resources that help families stay in their homes.

Families like the Orsaks.

It took weeks of scouring Craigslist, then canceling her cell phone service, spending all but $200 of her monthly income and luck, but Orsak finally found a rental home for $650 per month after almost three months of homelessness.

Tucked away in a quiet Victoria neighborhood, her family’s new home is a 1970 single-wide trailer that was recently valued at a meager $6,400 by the tax appraiser. Faded white and teal paint cover the trailer, which looks like a shell of a house because it’s missing proper flooring, has exposed nails sticking out of boards and water stains across the ceiling. It is missing furniture, beds and most household belongings, too.

“It’s not a real gold ring,” she said. “If it was, it wouldn’t be in your hand.”

There is a large, grassy backyard though, where Orsak’s children play with makeshift swords and sticks as she watches them from the porch. She explains that squeezing seven children into just two bedrooms and one bathroom is difficult, no doubt. But it’s much better than cramming her family of eight into two beds at a motel. Or worse – sleeping in the van.

Even with all its flaws, the weathered trailer house represents security. Studies, common sense and personal experience tell Orsak that her children are more likely to struggle both emotionally and in school if they don’t have a stable home. It’s the dangerous intersection of motherhood and poverty – what happens now has implications for her children’s future. This reality is worrisome: These days, neighborhoods where children grow up, in addition to their family’s race, income and education can influence their health and success later in life.

At least in all this, Orsak said, her children will learn one thing: how to scramble back on their feet when life kicks them down. The mother watches from the porch as they play near the street, squeals and laughter echoing across the property. Her 5-year-old pedals a pink and purple bike with a flat tire toward the street, and her older sister, Shelby, follows on a scooter. When the two girls travel out of sight, their mother yells to them to come back to the porch.

“I hate living here,” 10-year-old Shelby argues as she stomps up the porch steps. “You won’t even let me have fun.”

“Your mama’s going to ruin your life,” her mother jokingly responds.

“Nothing’s cool here,” the little girl whines, until her older brother, Aarin, cuts her off.

“It’s good,” the 11-year-old boy said. “It’s better than being on the street.”

[This story was originally published by Victoria Advocate.]