Residential treatment for traumatic brain injury victims

Victims of traumatic brain injuries often fall through the cracks of the system of care in Virginia, particularly those with behavior problems. Injuries often cause problems like impulse control and anger issues. These victims often ping-pong from one facility to another because their behavior gets them thrown out. They need structured treatment but few long-term residential facilities that specialize in brain injury rehab take government insurance like Medicaid. This is a population that is growing because improvements in emergency medical care have saved more people who suffer brain injuries in accidents. Also, more military personnel are surviving traumatic brain injuries sustained in battle. People with severe mental problems, dementias and disabilities such as autism also sometimes have these behavior issues that make them difficult to place.

I have had a long-time interest in this subject, and spent some time at a clubhouse for people with brain injuries last year. During that time, I became aware that many people stop receiving rehabilitation after a certain point in time, and their families struggle to care for them. Most of the people I talked to at the clubhouse had family who cared for them, but the directors of the clubhouse told me about others who had developed such severe behavior problems that their families were unable to care for them any more. They would move from one facility to another, and sometimes even land in jail. I wanted to profile a few of those families. I thought it was sad that their medical condition made them difficult to be around, and thus harder to treat. While medical technology saved them, society has not yet figured out how to save their quality of life.

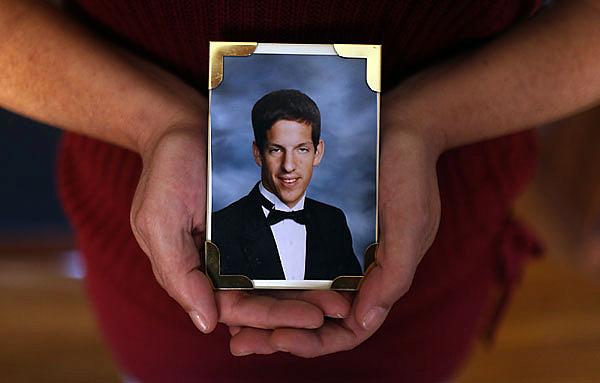

After a long struggle to find a home for her son, Sandy Tyler sent her son Frank to a Massachusetts facility.

Sandy Tyler's letter began simply enough: "Dear Somebody."

Her son had suffered a brain injury in a 2006 car accident at age 23. After a lengthy hospital stay and a stint in a rehab center, he returned to Tyler's Yorktown home. But the part of his brain that controlled his impulses no longer worked.

He punched and kicked and bit her.

After seven months, Frank Leonardi moved to a nursing facility in Hampton, but less than a year later, he hit an elderly woman in the face.

Administrators told Tyler she had 30 days to find another home for him.

She couldn't.

So she wrote a letter asking for help and sent it to the governor, legislators and officials across the state:

"He is not paralyzed. His brain just does not control his body. He can hold a fork and feed himself. Other than that he is left being aware of his situation, now 25, sitting in a wheelchair in a nursing home with elderly people. He hates his situation. He is angry. He has no impulse control, and when he gets mad he swings and hits or bites. He is like a 2-year-old grown man."

While rare, stories like Tyler's are becoming more common. In recent decades, survival of accidents and strokes has dramatically improved because of high-tech trauma centers and 911 services. Relatives laud the medical know-how that saved their loved ones, but say another nightmare begins when they're discharged.

Insurance stops paying for what's called "cognitive" rehab, and there are few residential treatment centers that take government insurance, or even private insurance after a certain point. People who are wealthy, or have workers' compensation or a lawsuit settlement, can find care, but most others cannot.

A portion of them have injuries that damage the ability to control their impulses. People with dementias and brain disorders such as autism also are subject to these behavioral problems. Without structured treatment and activities, they lash out.

Earlier this year, a group of brain-injury experts from across the state published a report on this issue, drawing on their own research and experiences, and government documents. The Virginia Brain Injury Council found that little has changed since a state watchdog agency report in 2007 that said:

"There is virtually no system of care for individuals with behavior problems resulting from a head injury who cannot afford private care. As a result, such individuals may be placed in a nursing home or incarcerated in a local jail or state prison, where the person is unlikely to receive needed services."

An estimated 250,000 adults in Virginia have brain injuries. Many families exhaust their income trying to care for them, forcing the victims onto Medicaid, the state-federal insurance for low-income and disabled Virginians.

The facilities in the state that specialize in treating people with brain injuries are typically privately owned; Medicaid won't cover their cost because they're not nursing homes.

The situation is particularly dire for people with behavioral problems, who ping-pong from nursing homes to emergency rooms to psychiatric units and sometimes even jails.

"The fact of the matter is, the system falls apart once people go back into their communities, so it's a hidden epidemic," said Paul Aravich, chairman of the brain injury council and a neurologist at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

Some people with disabilities qualify for what's called a "Medicaid waiver," a program started in the early 1990s to shift the use of Medicaid dollars that normally would be used in an institution to home- or community-based care. In Virginia, there are waivers for people with mental disabilities, the elderly and disabled, and also for the developmentally disabled, which includes children who have brain injuries, but not adults.

A growing number of states - now about half - have established waivers specifically for people with brain injuries, but Virginia has not.

Anne McDonnell, executive director of the Brain Injury Association of Virginia, said that organization found legislative patrons to sponsor bills for such a waiver from 2004 until this year, when the recession dimmed their hopes.

Waivers that do exist in Virginia have long waiting lists because the state doesn't have enough money for the program. Brain-injury advocates aren't optimistic about legislators' funding a new one for the brain-injured when more than 6,000 people are already waiting for ones that exist.

She estimates that the organization has received 350 calls in the past several years from families looking for appropriate care. The brain-injured don't fall under mental health, so state psychiatric units aren't suitable, and they don't usually qualify for facilities that care for people with dementias such as Alzheimer's.

That means they often land in nursing homes that aren't a good fit for them. A lack of structured activity can lead to eruptions.

Robert Voogt, owner of the Neurological Rehabilitation Living Center in Virginia Beach, gets calls from these families every week. His residential center cares for 12 people with brain injuries, offering physical and cognitive rehab, vocational counseling and behavior management.

The cost? Anywhere from $700 to $1,850 a day, depending on the person's injuries.

"We probably accept one out of 10 people who call," Voogt said. "Most don't have the money."

He's talked with local families who have had to send relatives to New Hampshire, Massachusetts and North Carolina for treatment. In turn, half the patients at Voogt's center come here from other states, some paid for by government insurance. Some are veterans, for whom traumatic brain injury has become the signature injury of the war on terrorism. Veterans have more access to treatment, but those whose brain injuries go undiagnosed can be shuffled from place to place.

"The four most popular places for a brain-injury survivor are jail, home with a parent, a state psychiatric center, a nursing home," Voogt said. "Those are all inappropriate placements, except for at home. But when parents get to be 70 or 80, they can't care for them. The brain-injured person who is not violent, who is passive, sits in his chair and doesn't cause trouble, a nursing home will have them for 50 years. Plenty of nursing homes will take those guys."

But people with impulse and anger control issues are another story:

"We have two guys who, if it weren't for me, would be in jail."

The family of James McLamb of Chesapeake learned about the jail possibility the hard way. McLamb was 55 when he was hit by a truck while riding a bicycle in November 2008.

When his sister, Helen Barbato, and her daughter went to see him at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, doctors told them McLamb had a 5 percent chance of surviving.

"I couldn't wrap my head around what the doctor was telling me," Barbato said. "He had one cut on his face."

Then she saw brain scans that showed a shattered skull. He survived, but he wasn't the same.

"I've had to get to know him all over again," Barbato said. "He has outbursts, and things come out of my brother's mouth that would have never come out of his mouth before."

McLamb spent a couple of months at Norfolk General, then was moved to a Sentara nursing home in Norfolk. Barbato said he didn't want to be there, and he got into altercations with other residents. Court records show that he threatened and struck one resident and verbally threatened another.

The residents pressed charges, and he was given six months of probation.

In April, he threatened one of the same residents, who told police: "I was sitting outside and had a cup of coffee. Mr. McLamb came over and sat down between me and my coffee. He became angry and began cursing at me, threatening to kill me with his fist in my face. He then threw my coffee cup in the bushes."

The resident pressed charges, and McLamb was thrown in jail on a misdemeanor charge of abusive language. He stayed there for 31 days on a charge that doesn't typically result in jail time. Meanwhile, nursing home officials informed Barbato that McLamb couldn't return to the facility.

Alverta Robinson, director of clinical operations for Sentara Lifecare, couldn't discuss the specific case because of privacy issues, but said such situations are rare. First, she said, staff try to help brain-injured residents by keeping to a minimum triggers that set them off emotionally, and also by using medications. But unlike people with dementia, behavior of those with brain injuries can be erratic and unpredictable.

Federal health policies allow facilities to discharge residents who are dangerous to themselves or others.

That left Barbato scrambling to find another place for McLamb. At one point, a social worker from the jail called to say that McLamb would likely be released on his court date, because the charge wasn't serious enough for jail time.

Still stunned, to begin with, at the idea of a nursing home resident being in jail, Barbato questioned how they could release him to the streets: "He has a brain injury and you're putting him out with no place to go?"

Finally, she found a facility in Chesapeake that would take him.

Barbato said many people with disabilities have resources, "but get hit by a car and there's nothing for you. They're society's forgotten people."

Tyler felt the same way when she was faced with caring for her son. Before the accident, Leonardi lived in a Hampton apartment and worked in a restaurant. He had no insurance, so he was put on Medicaid after the accident. Tyler tried to find a brain-injury facility in Virginia to take him after his rehab, but none accepted that insurance.

She spent seven months caring for him herself, and ended up with bruises and bites and black eyes. She struggled to keep her job and care for her two younger children. When Leonardi went to the hospital after having a seizure, Tyler heeded the advice of someone familiar with how the system works.

She refused to take him back home.

He was moved to a nursing facility in Hampton. It wasn't long, though, before he lashed out at residents and nurses' aides there, too, so the facility called to tell her they were discharging him.

Again, Tyler refused to take him back, and penned the letter to state officials.

That set off a process in which city case workers contacted nursing homes throughout the state to see if they could handle such a patient. Failing to find one, state officials agreed to cover his care expenses through Medicaid at Braintree Manor Rehabilitation and Nursing Center near Boston.

The facility has two units for people with brain injuries. Leonardi, now 27, has been in Massachusetts since March. "This program he is in is perfect for his needs," said Tyler. "Every minute of the day he has an activity. But it costs $500 for me to go visit him. That's two car payments."

She recently spent money she had set aside for Christmas to fly to Boston because he had a seizure: "I had to be there for him and advocate for his care."

He's not the only Virginian there. Eric Fletcher, 48, of Virginia Beach, also resides at Braintree Manor. He had a motorcycle accident in 2005. He learned to walk and talk again, but part of his frontal lobe was removed, leaving him unable to reason or control his impulses.

Following a month in the hospital after the accident, Fletcher went to two rehab units and two assisted living facilities. He spent several months at home, interspersed with emergency visits to psychiatric units and hospitals after violent outbursts.

Two years after his accident, his wife, Kathleen Fletcher, learned the same code words that Tyler used.

She refused to take him back after a psychiatric hospital discharged him. He was turned down for care at facilities across the state, and in 2007, Medicaid officials approved him for care at Braintree. Fletcher said her husband has received excellent care there, but she wishes he could receive it someplace in Virginia. She has considered divorcing him to salvage what's left of her life, but she also wants to remain his legal guardian to make sure he gets good care.

"Every fiber of you has to get out there and fight," she said. "I didn't sleep for a couple of years. Why should my husband go to Massachusetts to get help? It's mind-boggling."

Craig Markva, spokesman for the Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, said families or case managers have to prove that no appropriate care exists in Virginia before an out-of-state placement can be approved.

Federal privacy laws restricted him from saying how many Hampton Roads residents are receiving out-of-state treatment. A Freedom of Information Act request revealed that 12 Virginians with brain injuries have been admitted to a facility or facilities in Massachusetts during the past five years at a cost of $380 a day per patient.

That compares with an average daily rate of $153 for Medicaid-funded nursing home care in Virginia.

Voogt said he's tried to convince state officials of the need for a brain-injury waiver, to no avail. He said the usual characteristics of the victims - male, risk-takers, combative - don't garner the same public sympathy as disabled children and older people.

Aravich said the Brain Injury Council recommends establishing a brain-injury waiver, and also amending Medicaid policies to allow brain-injured residents treatment at Virginia neurological facilities not designated as skilled nursing centers.

The same placement difficulties are shared by people with dementias and severe psychiatric illness - both growing populations. Aravich believes the various advocacy groups and state departments need to work together to serve those with behavioral problems, before more fall through the cracks.

"If you're combative and a threat to others, people don't want to be around you, so it becomes an endless dance of getting thrown out of nursing homes," Aravich said. "The facilities don't have the expertise to treat the underlying cause, so the behavior gets worse."

It's a small percentage of the population who fall into this category, but Aravich believes they have the same right to life and liberty as anyone else: "Where is the pursuit of happiness for an individual like that?"

Elizabeth Simpson, (757) 446-2635, elizabeth.simpson@pilotonline.com

This article was produced as a project for The California Endowment Health Journalism Fellowships, a program of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism.