SFUSD fires up Bayview teachers in hopes they will stick around

The series has received support from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of USC's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

One African American family, half a century of experience in SF public schools

How can San Francisco support its most vulnerable black residents? Help them succeed at school.

A legacy of mistreatment for San Francisco’s black special ed students

Learning While Black: Community forum

African American honor roll student says when teachers set the bar high, ‘you gotta go get it'

SFUSD program intervenes early to keep kids out of special ed for behavior

A Landmark Lawsuit Aimed to Fix Special Ed for California's Black Students. It Didn’t.

Lead Plaintiff In Landmark Lawsuit Gets 2nd Chance At Education — At Age 60

A Decade Of Work Leads To Nearly 90 Percent Black Graduation Rate For SFUSD

State Audit Of Program For Homeless Students Finds Undercount, Lack Of Oversight

This is part of an ongoing series “Learning while black: The fight for equity in San Francisco schools.” And this at the bottom:

Teaching can be tough — especially for educators who work in schools where families are scraping by, lots of kids face challenges at home and in the community, and they often score low on standardized tests. Add to that isolation and high staff turnover and you’ve got a recipe for a revolving door.

That’s been a problem for years in San Francisco Unified schools in the city’s Bayview district. But SFUSD administrators have been working hard to stabilize the workforce, and there are signs of success.

The 30th floor of the Salesforce building just South of Market Street is abuzz on a recent Wednesday, as dozens of teachers, after-school staff, literacy coaches and other educators catch up on their summers or meet for the first time.

Nearly all of them work for San Francisco Unified schools in the Bayview, in the city’s southeast -- some are from a Potrero Hill elementary school, and they’re here for the second annual Bayview Ignite.

Tamitrice Rice Mitchell, director of this cohort of schools, grabs a microphone and welcomes them to the borrowed space. It was provided courtesy of the software giant, which has come to symbolize the new San Francisco — one a world away from the Bayview.

“We wanted to make sure that you all felt welcome, that you were comfortable and knew that you were teaching and working in the most fabulous schools at SFUSD,” Rice Mitchell tells them.

The former long-time Bayview school principal came up with the idea for Bayview Ignite with her boss, Assistant Superintendent Enikia Ford Morthel. The duo — wearing matching day-glow orange today — teamed up three years ago. They did a lot of listening, and learned that Bayview educators felt isolated inside and outside their schools.

They also felt whiplashed by constant changes dictated from above, Ford Morthel explained. They needed some love.

“And we said that we were all trying to do the same work and so it made sense to do the work together,” she said. “We wanted to get people inspired and excited about this work and rally folks around a shared vision.”

Burnout has taken a toll in the Bayview, where staff turnover has long been the highest in the district, Ford Morthel said. The high-poverty schools serve a concentration of student groups that tend to post the lowest academic test scores — African American, Latino and Pacific Islander.

SFUSD Superintendent Vincent Matthews last fall laid out the challenges along with a plan to close the so-called equity gap — particularly for the district’s African American students. He has targeted wenty schools for additional resources. Of those gathered here, all but one — the one from Potrero Hill — are on the list.

Everyone who works in this part of the city knows the lift can be heavy.

“Some of the kids in the neighborhood, some of them suffer from PTSD, like trauma situations — early age — you know like death, violence,” said Jerold Robinson Jr., who works security at Dr. Charles Drew Elementary School.

He’s seen how hard it is for some families to just get by. Lots of parents, he said, work multiple jobs so aren’t home to put dinner on the table, so their kids rely on school meals to eat. Other parents need help finding employment.

Though Bayview Ignite acknowledges the dark challenges that many — but not all — the kids here face, it doesn’t dwell on them. After all, that’s the only narrative plenty of people tend to hear about this part of town. Instead, Bayview Ignite aims to unite educators around the resilience and potential of the students and families.

To keep teachers and staff coming back every day — and working as a team — Ford Morthel said, she and Rice Mitchell realized that they needed to steep staff in the neighborhood’s broader story.

“What are all the things that are positive and beautiful, and how do you get up every day and show up for the babies,” she said. “The history and the culture of the babies that we see is one of resilience, is one of overcoming, is one of just so much amazing and so how do we bring that in and welcome the babies with that perspective versus the deficit, ‘oh pobrecito.’”

As the program gets rolling, Ford Morthel speaks to the crowd from experience. Her single mom gave birth to her at 19-years-old and had to work hard so her daughter could succeed in life. And she did.

But, Ford Morthel continues, kids of color like her who come from communities of “low wealth” tend to only see themselves reflected in “the stories that say that everything we want to be high in, we low in, and everything you want to be low in, you’re high in. At some point I started to wonder, what the hell is wrong with me?”

Their job, she tells them, is not to focus only on reading or math or critical thinking, but to get to know “each and every” one of their students.

“I also need you to ground yourself in the history of the people that they come from,” she says, ”so that when they’re feeling down, when their scores didn’t go up you can say ‘Uh uh, lift that head up. Do you know who you are? Do you know who you’re gonna be?”

“If we’re gonna ask you to tap into their spirits, to spark something great into them,” she concludes, “we need to make sure it’s sparked into you.”

Each participant who walked into Salesforce this morning received with their name tag a snippet of colored thread. Ford Morthel now tells them to fan out, think about why they do the work they do, find others who are like-minded and tie their threads together.

It’s a bonding exercise, because connection matters -- with each other, the kids and the community. That can take years to develop. But it pays off. Robinson Jr., the security guard at Charles Drew Elementary, has been there for a decade. And he lives in the neighborhood.

“I get the uncle roll,” he said, “you know, somebody close to the family that they can relate to, that they can talk to, they can open up to, you know just have some type of relationship.”

That’s important because plenty of adults constantly come in and out of these students’ lives.

“The biggest thing that the kids need in our community,” he. said, “is consistency.”

When a district staffer presents the data for the past few years to the group gathered here, there’s a lot of good news. As-yet unreleased test scores on the state standardized tests for the 2017-18 year, though still low, have risen in both math and English, one PowerPoint slide shows. The perception of safety at school -- among 4th and 5th graders and teachers surveyed -- is up, too, by 10 percent over the past three years. That means the gap between the schools here and the district overall is starting to close.

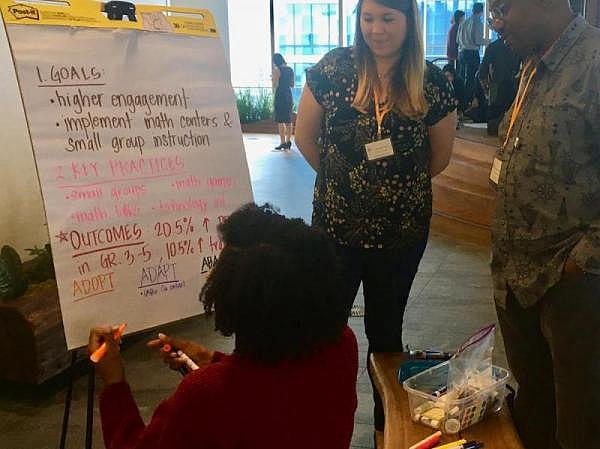

Educators from SFUSD's Dr. George Washington Carver Elementary School strategize about math instruction during a breakout session at Bayview Ignite. (CREDIT LEE ROMNEY / KALW)

As for teacher turnover? It was close to 36 percent for the schools gathered here in 2014-15, compared to 20 percent for the district overall. But preliminary data for this fall shows that the Bayview churn has dropped in half since then. Ford Morthel asks all the returning educators to stand up.

“Well hell,” she says with delight, “I say we did pretty well.”

Some educators are starting to feel the stability. Kelli Riggs is in her second year as an instructional coach at Bret Harte Elementary and served as a teacher there for four years before that.

“This is the first year I’ve been there that we’ve had some consistency and can look at our gaps” she said, because “normally, we’re just gearing up new people.”

In fact, Bret Harte only had to replace a single classroom teacher for this fall, said Principal Jeremy Hilinski. He’s now in his fifth year as the school’s leader, which he says makes him the longest serving principal in the Bayview right now. He’s tried to beef up camaraderie and collaboration among staff and it seems to be working.

Riggs said educators recently read a book together on culturally-responsive teaching. They’ve planned lessons jointly. And there’s the fun stuff, like a boat trip out under the Golden Gate bridge, and, she says laughing, “of course happy hours, because we’re teachers.”

There are some newbies, though. And the second day of Bayview Ignite is pretty much aimed at them. It’s also a refresher for those who are coming back.

Instead of the sweeping views of the Bay Bridge they got on day one from the Salesforce high-rise, the educators are on ground level in the Bayview today, prepping in their walking shoes for a scavenger hunt that will take them to some neighborhood landmarks.

They split into teams. Karina Garcia, 25, joins with four other teachers and literacy coaches.

Garcia just moved to San Francisco four days earlier and will soon be starting as a kindergarten teacher at Geroge Washington Carver Elementary School. She’s only taught for one year, but the East LA native came here specifically to work with Bayview kids.

“Almost everything I went to school for in terms of social justice — trying to work in a community like this, disrupting the narrative about black and brown kids — it’s all manifesting now in this school and this community and I’m so happy to be here,” she says as she clutches her paper map and heads down Third Street.

The group snaps selfies at each stop and checks off their list. There’s Auntie April’s Chicken-n-Waffles, the Joseph Lee Recreation Center, and the historic Bayview Opera House, now a community cultural and arts center.

Next they go into a tutoring center in a converted Edwardian house. It’s just one of a number of programs run by the nonprofit 100% College Prep. Associate Director Tashelle Herron Lane welcomes them, running through some of the organization’s other work, including tours of historically black colleges.

She’s thrilled to meet the literacy coaches.

“I’m gonna be coming to find y’all don’t worry,” she says as they rush out to continue their hunt.

Garcia, the new Kindergarten teacher, is thrilled too, with the whole event. You might even call her ignited.

“I feel already so much more prepared for this school year than I did last year,” she said. “I really like how collaborative it is. It’s almost like a big family and I just started yesterday with them.”

SFUSD schools started on August 20th. And district staff who put on Bayview Ignite hope the extra camaraderie and support might just help teachers like Garcia stick around for a while.

This story, from the series “Learning while black: The fight for equity in San Francisco schools,” was reported with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by KALW.]