Accused of abuse: Finding a voice, and a community

Beth and John Fankhauser in the theater lobby after the premiere of "The Syndrome"

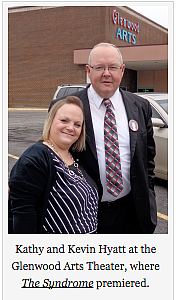

The premiere earlier this month of The Syndrome, a documentary that asks the hard questions about shaken baby syndrome theory, was even more thrilling than I’d expected: The film is riveting, and its first public showing, at the Kansas International Film Festival, drew a crowd so excited to meet each other that the lobby buzzed for an hour afterwards.

Beth Fankhauser was smiling, with tears in her eyes. “We thought we were the only ones,” she marveled. She and her husband John, who are now rearing their grandchildren while their daughter serves her prison time, met half a dozen other accused families that afternoon, reinforcing their decision to start speaking up after six years of waiting quietly and praying for justice.

“We allowed ourselves to be shamed… We thought we had to protect our family from the notoriety,” Beth explained, “But the system has betrayed us, and it’s time for the truth. I feel empowered to know that others are also walking this path.”

In a breakout session on the first morning, for example, pediatrician Robert Block named me personally as one of the child abuse denialists who have “fooled the media,” and some judges, into thinking there is a controversy in this arena. “I would ask the parents who are here whether they think SBS is a myth,” he admonished, pointing out that writing a blog requires no qualifications and no certification, just like writing a book or making a movie—like Flawed Convictions by law professor Deborah Tuerkheimer and The Syndrome. Block objected that all our works disregard the real victims—the injured babies—while focusing improperly on the perpetrators.

Prosecutor Shelley Akamatsu from Boise, Idaho, reported that prosecutors are pressing abusive head trauma cases harder than ever in the courtroom. She remembered the first shaken baby conference, in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1996, when “convictions in AHT cases were not common,” she said, because only a few prosecutors, those who had taught themselves, knew how to handle the medical content. Eighteen years later, national training programs have prepared prosecutors “to meet untrue defenses, prove the severity of the forces inflicted, and effectively educate jurors,” she said, so that now “convictions in AHT cases are the norm rather than the exception.”

Akamatsu called for an organized response now to defending these cases on appeal. “True justice means expertly defending the convictions we’ve worked so hard to get,” she said. “There’s a place for Innocence Projects,” she acknowledged, but “not in this arena, because these cases are so factually driven.”

Law professor Joelle Anne Moreno argued that the courts, the press, and the public are all misinformed about infant head trauma. She dismissed on legal grounds the adequacy of the “new evidence” that was behind the reopening of the Jennifer Del Prete and Quentin Louis cases, the reversal of the Audrey Edmunds conviction, and the minority opinion in the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Shirley Ree Smith case. “We need to clear up these legal questions,” she said. “Don’t confuse causation with culpability. That’s what Professor Tuerkheimer is doing when she says this is a medical diagnosis of murder.”

Dr. Sandeep Narang, who is both a physician and an attorney, dismissed the idea of any real controversy about abusive head trauma as a fallacy manufactured by the defense and parroted by the media. He devoted the first hour of his talk to the medical literature, concluding that serious brain injury or death from a short fall is “very rare,” bleeding disorders are easy to identify, and both subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhages are highly correlated with child abuse. The second hour he spent rebutting the “straw man” argument that shaken baby syndrome is “medically diagnosed murder.” He said he was puzzled by the claim that the child abuse literature exhibits circular reasoning:

There’s a lot of accident literature where we just looked at accidents. We didn’t look at abusive cohorts. We just looked at accidents. How is that circular?

Because Dr. Narang had the floor, no one answered his rhetorical question, but this is my blog posting, so please let me explain: These studies typically start with a series of patients seen at the authors’ hospitals over a period of time. Not infrequently, researchers studying accidental injury simply remove from the study any cases of presumed child abuse, with the stated goal of limiting the study to verifiable accidents. The filtering out of abuse cases is typically done by the local child abuse team, or sometimes by the authors. The problematic result is that, if a child comes in with a serious injury and a history of a household fall during the study period, the case is diagnosed as abuse and therefore never appears in the data. This self-fulfilling sorting algorithm also taints the studies that attempt to describe for physicians how to recognize child abuse—for an on-line example, please see http://archpedi.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=348423.

Which brings me back to something that bothered me when I first read the trial transcripts of the 1997 case that brought me into this arena: As long as the child abuse teams continue to treat every one of these short-fall reports as obvious abuse with immediate symptoms, there is almost no way to gather evidence to the contrary. Decades of convictions have been based entirely on sincere but unproven medical opinion, and at this point, the opinion is based on decades of convictions.

Several dozen child-abuse experts tried but failed to convince the organizers of the Kansas festival to pull The Syndrome from their program, as described at The Syndrome Trailer Makes Waves. For an interview with investigative reporter Susan Goldsmith, who made the film with her cousin Meryl Goldsmith, please see The Syndrome Promises Fireworks.

If you are not familiar with the debate surrounding infant abusive head trauma, please see the home page of my blog site.

copyright 2014, Sue Luttner