All for Antlers: Q&A with Ryan Sabalow of The Indy Star

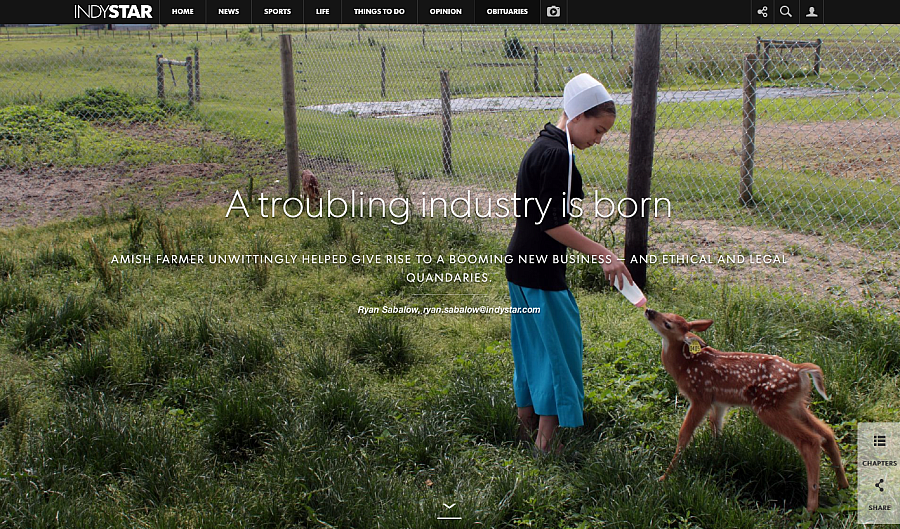

(Image from The Indy Star)

This is the second post in a two-part series. For the first installment, click here.

I first met Ryan Sabalow when he received one of USC Annenberg’s California Health Journalism Fellowships. He was a reporter at the Redding Record Searchlight, in Northern California, and his stories showed a ton of promise as he wrote about unnecessary surgeries, aging physicians, and wasted health spending, among other things. He left Redding for The Indianapolis Star in 2012, and this past month, he broke new ground with a series about the captive-deer hunting industry, titled “Buck Fever.”

I asked him via email to answer a few questions about his reporting. His responses are below. They have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: How did you start down the path of investigating game farms?

A: In 2012, we got a press release from the wildlife department saying that if you’re hunting in Southern Indiana and you see a deer with a tag in its ear, kill it. There had been an escape from an Indiana deer farm that had received animals from a Pennsylvania herd where animals tested positive for chronic wasting disease.

I’m a deer hunter, so I was immediately interested in finding out more. Since I grew up on the West Coast, I had no idea that the practice was so widespread elsewhere in the country. When I started seeing the huge antlers on the deer these guys were breeding and started finding out about federal criminal cases involving deer breeders, I knew I had something that deserved a closer look.

Q: This seems like an area where you might not have much of a paper trail to follow. What sort of records did you get access to and how?

A: We filed records requests in all 50 states to try to find out just how many deer farms and hunting preserves there are around the country. This proved to be a major undertaking.

Each state does things a little differently. Some states classify them as livestock, under agriculture departments. Others classify them as wildlife, under wildlife agencies. Many states have joint regulatory authority between the two. So we ended having to file requests with both agencies in many states.

Some states were very forthcoming. Others were not. A few never got back to us or denied our requests. It was interesting to learn that in a couple of states, the agriculture lobby has succeeded in writing exemptions to public records laws, forbidding the release of location information for farming operations. That’s something health journalists might be interested in, given concerns about food safety and livestock-borne diseases.

Wisconsin tried to charge us hundreds of dollars for its deer-farm database. We pushed back with the help of the state’s public records advocacy group and got them to give us the records for free. We also filed requests with the USDA to try to get a comprehensive list of positive TB and CWD deer on farms. The agency complied and sent us, free of charge, a big pile of disease records, but it was only a few years worth. Plus, the location information was so heavily redacted it was all but useless.

For Indiana’s TB outbreak, both the wildlife agency and agriculture department provided vital info about how costly one of these outbreaks can be for taxpayers and the amount of manpower that goes into tracking and containing it.

Q: There are a lot of animal-borne diseases that have never made the leap to humans, and the threat of that leap plays a role in your series. How did you go about deciding which pieces of the health angle to emphasize?

A: Many non-hunters have no idea the amount of venison that gets eaten in the U.S. each year. Hunters consume tons of the stuff. The CDC advises them to use caution when eating meat from areas where CWD is endemic. There are some folks who are very concerned that as CWD spreads in wild deer around the country, this prion disease could someday make the jump to us. While it hasn’t happened so far and the risks appear to be minimal, the threat is pretty troubling considering CWD appears to spread from bodily fluids among deer, and the infectious agent is so hearty it can bind to the soil for decades.

Bovine TB has cost taxpayers hundreds of millions of dollars and major headaches for the cattle industry in places like Minnesota and Michigan, where wild deer were spreading the disease to cattle. Because of pasteurization and slaughterhouse testing of cattle, bovine TB doesn’t infect humans very often in the U.S., but there is a health concern as more folks drink raw, unpasteurized milk and hunters come in contact with the carcasses of infected deer.

Q: How did you get so many hunters and business owners to talk with you about business practices that are clearly under a lot of scrutiny right now?

A: I worked on a cattle ranch for a number of years as a young man and I’m a lifelong hunter, so their practices don’t shock me or make me squeamish. Plus, I genuinely wanted to hear what these folks had to say, which is why we spent hours letting them tell us their perspective. I was and still am genuinely fascinated by what they do and the stories they told us.

Q: What were some of the biggest hurdles you had to overcome when reporting this series?

A: It was my first multipart investigative series, so it was a challenge staying organized and figuring out what the most important aspects of the story were. It took forever to transcribe most of the interviews we did, but it proved vital during fact-checking time. The Indianapolis Star, while a decent-sized publication, also isn’t quite big enough to have a reporter work on a story like this full time, so I had to juggle other daily assignments and investigations too.

Q: What has the response been like from hunters, conservationists, and just everyday readers?

A: The reaction from wildlife officials and biologists has been really nice. A number of them from around the country have sent notes to my editor praising us for our accuracy and thoroughness.

The reaction from the hunting community also has been neat to see. Andrew McKean, the editor of Outdoor Life, did a blog post about the project, saying hunters need to take an active role in the debate. Boone & Crockett and Pope & Young, two trophy hunting organizations, also began aggressively posting position statements after the stories published, condemning the commercialization, genetic manipulation, disease risks and unsporting aspects of the deer-breeding industry. There have been a lot of really nuanced discussions on hunting message boards across the country.

Non-hunters also took interest. Michael Markarian, the chief program and policy officer of the Humane Society of the United States also did a piece echoing those concerns.