Ban on mixing hospital scrubs and sandwiches gains currency

Antidote's series on whether wearing scrubs in public places like restaurants leads to more infections is on the cusp of generating some meaningful change in the way health care organizations address scrubs and other potential disease carriers.

Antidote's series on whether wearing scrubs in public places like restaurants leads to more infections is on the cusp of generating some meaningful change in the way health care organizations address scrubs and other potential disease carriers.

The series has led to more thought-provoking ideas and comments than I can adequately address. The initial notion came from Dr. David C. Martin, who wrote forcefully that surgical scrubs in public were a public health threat.

After seeing the series, Larry Husten, the sharp-minded writer behind CardioBrief and the news director at the New England Journal of Medicine's CardioExchange site, contacted me about the same issue. He wanted to invite Dr. Martin to write about scrubs for the Exchange. I put the two of them in touch, and Dr. Martin wrote more directly to practitioners, saying:

Physicians are quick to raise the red flag when policy is thrust upon them, so why not be more proactive and give this issue the attention it is due? The AMA News reported that Washington State Representative Tom Campbell addressed the rising MRSA-related infection issue by introducing a bill and stated, "If hospitals won't take meaningful steps to stop drug-resistant infections, then we'll pass legislation to make sure they do." How many readers of CardioExchange welcome this brand of change through legislation? I would prefer a more proactive approach among those most qualified to study this issue and render sound policy guidelines, and greater compliance by those who feel they are above the rules.

Not long after that post went up, reporter Sara Okeson from the News-Leader in Springfield, Mo., contacted me about Antidote's series and told me she was considering writing about scrubs and other possible infection pathways. She asked if I could put her in touch with Martin. I did. She interviewed him and wrote Scrubs: Can hospital uniforms spread germs, disease?

She quoted Martin, saying, "It just makes sense to not take a means of transmission out into the community."

She also spoke to someone Martin had quoted in his piece, Betsy McCaughey, the former lieutenant governor of New York and the chair of the Committee to Reduce Infection Deaths .

McCaughey is a controversial figure, of course, having helped torpedo the Clinton era health care reform and helping spread misinformation about "death panels" during the most recent health care reform debate. But, on this issue, McCaughey spoke in terms uncolored by politics.

"Most of the hospital infections aren't occurring in the operating room," McCaughey told Okeson. "MRSA pneumonia infections aren't occurring in the operating room. Most of these germs contaminate all areas of the hospital. It shows a real lack of consideration for the public that hospitals allow some employees to wear this clothing out of the hospital and into the public."

Lastly, it may be a coincidence, but as all of this conversation has been happening, the issue of scrubs has now been brought into a broader piece of dress code legislation in the New York Legislature. UPI wrote NY may ban germy doctors' ties, lab coats. The story says:

The New York Legislature is considering a bill that would prohibit healthcare professionals from wearing neck ties or jewelry that may carry bacteria. Areas of examination would include: Barring neck ties for doctors and hospital workers in a clinical setting. Requiring hospitals to provide an adequate supply of scrubs to medical staff to ensure they are changed often. Ban the wearing of uniforms outside of the hospital or other healthcare setting.

The story also cites some evidence supporting a ban:

Similar dress codes were implemented in St. Louis and there was a 50 percent reduction in hospital-acquired infections, while a hospital in Indiana, which adopted a hygienic dress code upon opening two years ago, has no reported instances of hospital-acquired infections. In 2004, a New York study found the neckties worn by physicians had an eight-fold greater increase of harboring pathogens than ties worn by security personnel wearing neckties in the same hospital.

The Indiana reference is definitely on point. It comes from Monroe Hospital in Bloomington, which, upon opening in 2006, started giving all staff laundered scrubs and barred them from wearing scrubs outside the building. McCaughey wrote in Wall Street Journal in 2009 that the hospital has had no hospital-acquired infections since opening.

The St. Louis reference is a bit more murky. It also comes from McCaughey's piece in the Journal, where she wrote that, "St Mary's Health Center in St. Louis reduced infections after Cesarean births by more than 50 percent by providing all caregivers with hospital-laundered scrubs, as well as requiring caregivers to double-glove." Because of the glove policy, the effect of the laundered scrubs is a bit muted. Dirty hands, everyone agrees, are the most significant disease carrier because hands come into the most contact with the patients and everything else.

Clearly, as Julie Hallisy from the Empowered Patient Coalition and others have pointed out, there needs to be more and better research into the effect of scrubs on infections and the best ways to reduce infections overall.

Have a comment? Write askantidote@gmail.com

Follow Antidote on Twitter @wheisel

Related Posts:

Hospital scrubs and sandwiches should not mix

Hospitals must change surgical scrub culture from within

Superbugs may show up wearing hospital scrubs

Hospital scrub scrapping, and patient safety, can start with one tough conversation

Doctors sound off - loudly - about wearing scrubs on the street

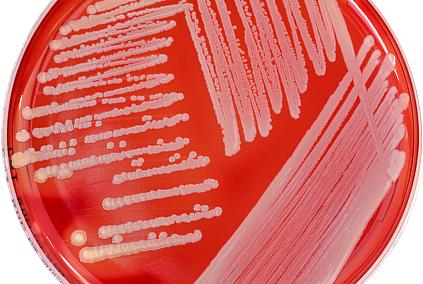

Photo credit: Staph A in petri dish/iStockphoto.com