The Burning Seasons

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/U.S. Forest Service

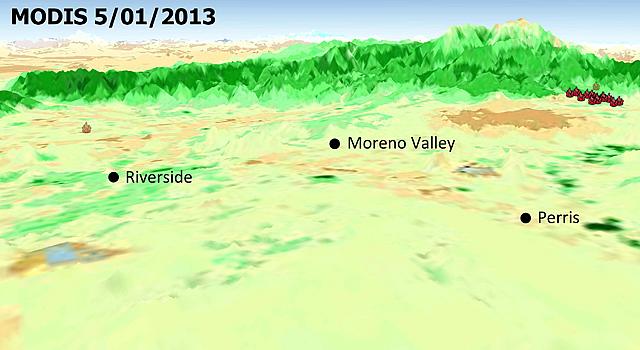

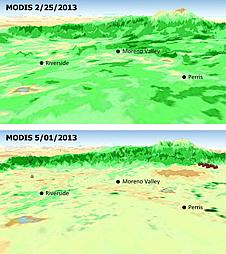

As wildfires continue to rage across Colorado, California is on the brink of a particularly destructive and lengthy fire season. Satellite images studied by scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Chapman University indicate that this year’s abnormal rainfall patterns have set Southern California up for a volatile wildfire season. Basically, rains early in the year caused vegetation to grow, but a subsequent drought left the plants dry and ready to fuel wildfires (see image below).

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/U.S. Forest Service

By 2050, the USDA Forest Service expects that a changing climate could increase wildfires by 50 percent across the U.S., and over 100 percent in areas of the West. Years of drought and open spaces in western states make this region especially fire prone. Already fire seasons are more destructive now than in the past, and each year surpasses the previous one for record setting fires.

In 2012, the severe drought that gripped the Great Plains, combined with high temperatures and strong winds, contributed to much of the more than 9 million acres burned across the country. That was up from a peak of seven million burned in the 1960s, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. This year’s wildfire season is no exception and got off to an early start with record-breaking conflagrations this past month in Colorado. The Black Forest fire, near Colorado Springs, is the worst in the state’s history, and blackened 25 square miles, incinerated 419 homes, forced the evacuation of 38,000 people, and claimed two lives, surpassing the carnage of 2012’s Waldo Canyon fire, which was then considered the state’s worst recorded blaze.

Fires are closely tied to climate: the hotter, dryer weather and droughts that experts predict will occur in the coming years will suck the moisture out of plants and trees, creating the fuel that feeds these blazes. But it’s not just the parched landscape that will drive this rise, studies show. The fires themselves create feedback loops that can amplify global warming.

For starters, wildfires in the continental U.S. and Alaska pump enormous amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere—about 290 million metric tons annually, which is equal to four to six percent of the nation’s CO2 emissions from burning fossil fuels for an entire year, according to research conducted by the National Center for Atmospheric Research. And especially large infernos spew massive pulses of this greenhouse gas into the skies. The “striking implication,” the authors noted, is that severe fire seasons that last only one or two months can dirty the air with as much of this greenhouse gas as vehicle emissions in some states for the entire year. Plus, smoke particles reduce the amount of solar radiation absorbed by the atmosphere, which inhibits cloud formation and rainfall, leading to more droughts, a 2013 study by U.S. Forest Service scientists showed. Consequently, fires beget more fires in a self-perpetuating cycle.

Increasingly hotter weather can also alter ecosystems in ways that make forests more vulnerable to wildfires. In the Northern Hemisphere, hundreds of millions of pine trees on millions of acres across the West have been denuded by bark or white pine beetles. The insects bore through the protective bark on trees, and infect them with a fatal fungus that kills the trees. Left behind are brittle husks that provide kindling for these blazes. Increasing temperatures are largely responsible for the widespread infestation: the beetles are now able to survive the warmer winters instead of dying in the frigid weather, longer summers enable them to reproduce twice a year instead of once. The beetles can fly further, extending their range, while warmer overall temperatures means they can survive at higher altitudes and latitudes.

In Colorado alone, more than 3.3 million acres of forests have been felled by these tiny insects, while just one species, the mountain pine beetle has destroyed more than 70,000 square miles of trees, which is roughly the size of the state of Washington. “In Canada, there are fears they could wipe out the whole Boreal forest,” Christine Wiedinmyer, an atmospheric chemist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, told me when I interviewed her for my upcoming book, Fevered. “There would be no trees in Canada—one of our largest ecosystems and carbon sinks in the world—which would be really catastrophic. And there’s nothing we can do about it.”

More research needs to be done into the health effects of wildfires, but one recent study proved troubling. In June 2008, a lightning strike ignited a peat bog fire that raged for months in a rural area of North Carolina and spread into the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Researchers collected data on emergency department visits for cardiac and respiratory conditions from more than 100 hospitals in eastern North Carolina counties exposed to the fire. The dense smoke plume produced “haze and air pollution far in excess of the EPA’s National Ambient Air Quality Standards,” the agency noted. In the surrounding area, there was a corresponding increase in rates of asthma, pneumonia, acute bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and a 37% spike in patients with symptoms of heart failure and other cardiac problems. This consistent across the board increase in these health risks is “striking and persuasive,” researchers concluded, “and has potentially significant public health implications.”

Linda Marsa's book FEVERED will be available on August 6, 2013, wherever books and e-books are sold.