Community engagement helped reveal the hidden health costs of high electricity bills in California

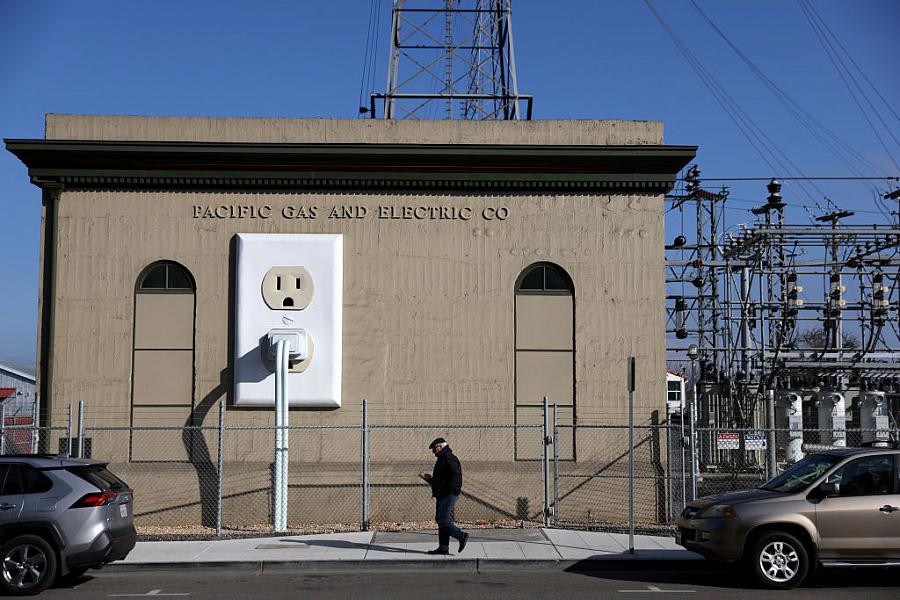

(Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Skipping meals, chronic stress and downsizing homes — these are just a few ways customers of Pacific Gas and Electric Company told me high bills were affecting their lives.

PG&E has hiked its rates four times this year. The latest rate hike, which will add about $6 to the average customer’s monthly bills, will go into effect Oct. 1. But PG&E’s rate hikes aren’t the only driver of increasing costs. This summer, unprecedented heat waves combined with historically high electricity rates. California’s inland residents especially suffered. Bakersfield residents endured at least 11 consecutive days in July where temperatures reached more than 105 degrees Fahrenheit.

Despite media attention surrounding PG&E’s rate hikes, few news stories examined what this meant for residents in the state’s hottest regions. My reporting aimed to find out how inland residents were coping. Over several months I ran a “Show Me Your Bill” campaign. The effort included a short questionnaire and asked people to share their highest or most recent bills with our newsroom. More than 80 people responded and told us stories about what they’d had to sacrifice to keep their power on.

“We cannot afford food now,” one survey respondent wrote. “We have had to cut back. We are hurting.”

“I do not turn on the heat, use a jacket instead, use a headlamp in my home to cut down on costs,” wrote another.

I believe people were willing to share their stories in part because of frustration with their lack of control over rising costs. Residents felt the California Public Utilities Commission, the state agency that regulates PG&E’s rate increases, had done little to limit how much the company can charge. Many respondents wanted a space to be heard. Their stories were essential to framing the overall project and the series I reported.

Running the “Show Me Your Bill” campaign

I used the questionnaire to find sources, analyze individual bills and report overall trends. I tried to keep the questionnaire short, while still collecting necessary demographic information and leaving room for open-ended questions where people could share their experiences. Respondents could participate in the reporting to varying degrees — by following up with a reporter for an interview or sharing their experiences anonymously. I also asked respondents to attach their bill. I used the bills to analyze how upcoming changes to how PG&E bills for electricity would affect people in different locations. I learned that the change would be mostly beneficial for inland residents, while coastal residents would shoulder more of the costs.

Tip: The option to participate anonymously was valuable because more people were willing to answer the questionnaire if they didn’t have to go on the record. I also made sure most of the questions were optional, so those who were unable to send in a bill could still share their stories. Their answers helped paint a picture of how residents across the state were coping with rising rates and gave me a better idea of the scope of the issue.

How I reached people

I wanted to reach residents across California’s North and Central Valley. This required finding creative engagement ideas in regions where I didn’t have existing connections. North State Public Radio is based in Chico, but we have partnerships with other public radio stations in the state. I partnered with Valley Public Radio in Fresno, a more trusted organization for people living in that area. We aired callouts that directed people to fill out the questionnaire on the VPR website. North State Public Radio also aired callouts to point our listeners to the same questionnaire.

We also posted the questionnaire on social media, including targeted Facebook groups, Nextdoor, Reddit and Instagram.

Reddit was by far the most successful social media platform. We posted in geographic subreddits to reach people in specific Central Valley communities. There were also a lot of people who chose to share their experiences in the comments without filling out the survey.

What I asked

I asked basic questions about people’s experiences. For example, whether or not they had been disconnected from power due to nonpayment or if they had to cut costs in other parts of their lives to pay their bills. Checkboxes with several options took less time for people to fill out than short answer questions and I opted to use those for most of the questionnaire. However, I also wanted the questions to be open-ended, so that my assumptions didn’t drive the reporting. I included a short answer question where respondents could write about anything they wanted to share. I also asked respondents what questions I could answer for them.

The final two short answer questions were probably the most useful in the questionnaire because I could identify trends in people’s experiences. I also learned many respondents weren’t aware of various aid programs that could help them with past-due bills. This inspired an additional story in the series, titled “Summer cooling costs projected to be the highest in a decade; here’s how to get help with your bill.”

What I’d do differently

While I’m extremely proud of the stories my engagement work led to, there were some things I would have done differently. The first is to readjust my expectations for the survey and to pivot accordingly. I had envisioned the questionnaire primarily as a way to get in touch with sources for interviews. However, few who responded to the questionnaire agreed to follow up for an interview. In retrospect, I would have asked more pointed and strategic questions that dug directly into health implications; such as having to cut grocery costs or turning off the AC to afford the electricity bill. This would have helped me report more specifically on people’s experiences without needing to follow up.

I also would have worked directly with community organizations to reach hard-to-reach and vulnerable communities. I tried to address this by using targeted Facebook groups, but working directly with organizations that already had a relationship with community members would have been more successful.

How this project will shape future reporting

This series was incredibly difficult to report because each story unlocked another that needed to be told. It was challenging to stay focused and not get sidetracked by new questions that arose after each interview. I now have a list of at least five more story ideas. I feel this is one of the most valuable outcomes of reporting this series. I have a much deeper understanding of how little we know about this issue and what additional topics need to be explored.

Next, I plan to dig deeper into how emergency funding to help people keep their lights on has declined despite the rising cost of electricity. I also learned that the rate-setting process is incredibly complicated, which makes it difficult to advocate in Sacramento ahead of the most important proceedings. I’d like to continue to pull back the curtain and demystify why costs are on the rise so ratepayers are empowered to advocate for themselves most effectively.