COVID-19 amplified the disparities for minority kids with disabilities

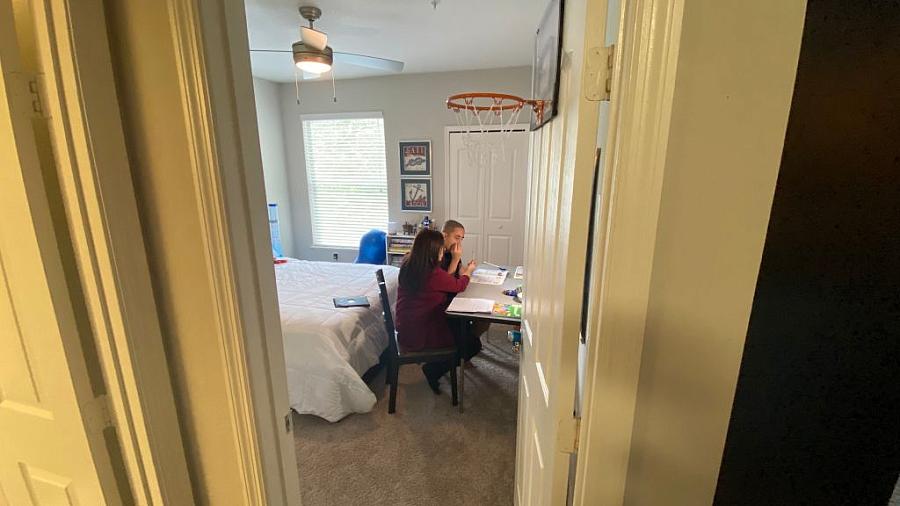

Aracelis Bonet, 50, home schools her son Adam Martinez, 14, who is affected by severe autism, in their home on October 1, 2020. The Orlando, Florida real estate agent decided to largely put on hold her job as a real estate agent to make sure her 14-year-old son had the constant care he needs.

(Photo by Gianrigo Marletta/AFP via Getty Images)

The gap in funding and access to care and crucial services for Black, Indigenous and Latino children with disabilities compared to their white peers has been a longstanding blight on the education and health care system. And that was before the pandemic closed schools.

“COVID only made things worse. Delivery of services came to a screeching halt,” said Dr. Geeta Grover, director of the UC Irvine Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders who cares for children with learning disorders, attention deficit disorder and autism.

She said without school, the kids lost a multitude of supports, such as therapies for speech and learning, as well as their predictable routine, which can be especially traumatic for kids with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). For example, she described one boy who went to his bus stop every morning for weeks after schools closed.

“Without robust services, the kids can’t stay on their (learning) trajectory,” said Grover.

More than 3 million children 18 and younger in the United States have a disability, according to 2019 American Community Survey.

Many of those kids abruptly lost their support system when schools closed, and minority children were harder hit, according to the U.S. Department of Education (DOE). The department and child advocates fear that the disruptions in education and support services for kids with disabilities may cause long-term disparities in their academic achievements, which can shape later-in-life health and well-being.

For decades, researchers have documented disparities for minority kids with disabilities at every step of their journey, from delayed diagnoses to difficulty in getting appropriate support services.

Ana Ramos, a Latina mother of two boys with developmental disorders, knows the struggle to get help. Gustavo, 8, finally completed his evaluation for autism in March, though the diagnosis has been suspected since he was a toddler because of delayed speech and unusual behaviors. He didn’t meet criteria for autism, but has an unspecified developmental disorder. Ramos’ 6-year-old, Geraldo, was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at 32 months and receives services through school and at the UCI Center.

Asked if her boys are getting what they need at school, Ramos, speaking through an interpreter, said: “To be honest, no.”

Ramos said Gustavo’s kindergarten school didn’t meet his needs as he was bullied and despite requests, the teacher didn’t arrange for an evaluation, so she moved him to a new school for first grade. That teacher there referred him for developmental testing, but the process stopped when COVID-19 closed schools and only recently resumed.

Gustavo’s experience is far from unique.

Many support services, including assessments, psychotherapy, therapy for speech or behavior and many others, are provided in school settings, which meant they suddenly stopped when schools closed. Nearly half of special education services are provided by Medicaid and CHIP, especially for children with greater needs, Additional funds come from other federal, state and local government programs.

COVID-19 also led to a steep drop in kids’ doctor visits. Among children insured with Medicaid and CHIP, 44% fewer had routine checkups, and thus, fewer developmental screenings, in 2020 than in 2019. Missing out on visits and screenings could cause delay in recognizing developmental disorders.

Delayed diagnosis for minority children and non-English speakers has been observed repeatedly. Nationwide, Black and Hispanic/Latino children were diagnosed with ASD and intellectual disabilities on average later than their white peers, according to a 2020 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, for the first time the rate per 1,000 white and Black children diagnosed with autism was similar, though the rate for Hispanic children diagnosed remained lower.

Delayed diagnosis and early intervention can interfere with children reaching their full potential, and negatively impact the quality of life for the whole family. For example, early intervention can improve the ability to communicate for children with autism. And babies with hearing loss who receive hearing aids before age 6 months have improved communication, language skills and school performance compared to babies who don’t receive hearing aids.

That’s why the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends universal developmental screening of all children to catch problems as early as possible. Screening can also occur in preschools. However, minority children and those from non-English speaking or low-income families are less likely to have access to routine health care or attend high-quality preschools where such screenings take place.

Grover said, “Diagnosis is the least of my concerns, but diagnosis opens doors to services and that’s what matters.”

However, even when children of color are diagnosed with a disability, they are less likely to receive as much funding for support services, as their white peers. Less funding translates to fewer services, which in turn can lead to poorer outcomes for the kids. Children from low-income families simply “go without” as their families don’t have the money to pay for specialized services, such as applied behavioral analysis. The treatment can be expensive, though it has proven benefits for behavior and communication skills for children with autism.

For example, in California, children of color with disabilities received less funding than their white peers from regional centers through the state’s Department of Disability Services. On average, Black and Asian children received about 11% less and Hispanic children received as much as 47% less than white children.

The reasons that minority children are diagnosed later (even with similar symptoms) and receive few services are complex and intertwined, according to research based on interviews of providers and parents of children with development disorders. Black and non-English speaking parents reported feeling “undervalued” by professionals, including not having their concerns acknowledged. Other barriers included differences in families’ expectations for their child’s development, lack of culturally informed care, the denial of diagnoses by some ethnic minorities due to the stigma of having a child with autism, lack of accessible resources due to problems with transportation, conflicts with work schedules, or no services available in their community, among other factors.

National data are limited, however. Kaiser Family Foundation reported that COVID-19 led to deepening of disparities in special education services for children with disabilities who are covered by Medicaid and CHIP.

“There’s a national shortage of data,” said Sean Luechtefeld, director of communications for American Network of Community Options and Resources (ANCOR), a trade group that advocates for frontline providers who care for individuals with disabilities.

The lack of funding leads to low reimbursement rates for service workers, exacerbating a persistent workforce shortage in the field. COVID-19 worsened the shortage as some agencies closed and workers could get higher paying jobs elsewhere.

The Case for Inclusion, published by ANCOR and United Cerebral Palsy, reported in 2022 that more than 580,000 individuals of all ages with disabilities were parked on waiting lists for services.

“We can’t clear the waiting lists without an adequate workforce,” said Luechtefeld.

He encouraged journalists to look deeper than the numbers. Quoting a mentor, he said, “When it comes to data, the numbers don’t lie, but they can obscure the truth.” Waiting lists show the numbers of clients without services, but they don’t answer why.

Ramos said agencies should have more staff that speak Spanish and other languages, and the process for children to get evaluations and services shouldn’t take so long.

Despite the difficulties facing families, Ramos remains optimistic for her sons, who are receiving some services, but Gustavo doesn’t yet have a full treatment plan.

Tearfully she said, “I want to share with everyone there is hope, though it has not been easy, (find) all the services available to you. “My sons are now talking. The goal is for them to be as independent as they can be.

**