The Curse of the Big Idea: Be Wary of Paradigm Shifts on PowerPoint

President Theodore Roosevelt called them nature fakers.

These were writers - some scientists and some not - who stretched the bounds of science to create a more romantic, more dramatic, usually more anthropomorphic vision of the natural world.

"The highest type of student of nature should be able to see keenly and write interestingly and should have an imagination that will enable him to interpret the facts," Roosevelt wrote in 1907. "But he is not a student of nature at all who sees not keenly but falsely, who writes interestingly and untruthfully, and whose imagination is used not to interpret facts but to invent them."

What would Roosevelt make of the parade of scientific claims first marketed through magazine cover stories and PowerPoint talks as breakthroughs only to be proven with increasing regularity to be more fiction than fact? These are the Big Idea science stories that have everyone marveling and talking for days, weeks, years even, only to be deflated, sometimes by the same journalists who first inflated them.

Obesity is contagious! And so is divorce!

Rapid climate change over the next decade will have "deadly consequences for global food production"!

But maybe not.

Bread is really bad for you, so butter roast beef instead!

Or perhaps things are a bit more complicated.

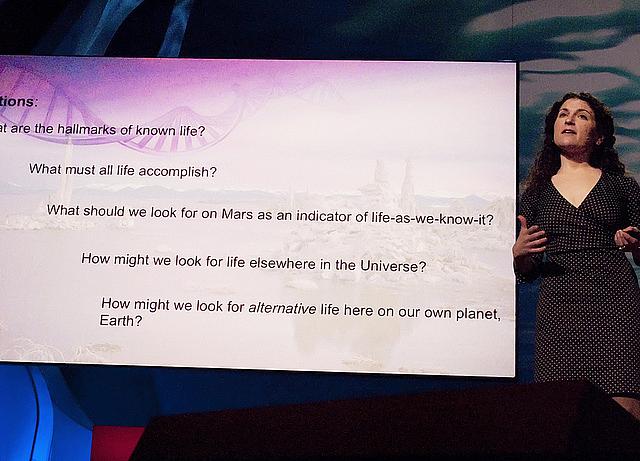

Alien life forms are swimming in a California lake, "one of the most significant scientific discoveries of all time"! (Left: researcher Felisa Wolfe-Simon at the 2011 TED conference)

On second thought, we're not so sure.

In denouncing the nature fakers, Roosevelt referred to what was then one of the biggest scientific breakthroughs-cum-boondoggles of the era: the Cardiff Giant.

The purported discovery of a petrified giant buried in upstate New York was one of American journalism's first Big Ideas. It challenged traditional thinking about the evolution of humans and the entire history of the world. It prompted people to line up for a chance to see the giant and hear men acting like scientists talk about these Big Ideas. And it was a complete fraud.

The Cardiff Giant was such a big deal at the time that P.T. Barnum had a fake giant made so that he could share in the profits, which famously prompted David Hannum, one of the owners of the original fake giant, to say, "There's a sucker born every minute."

The recent series of too-good-to-be-true scientific claims can't help but make you think that we've learned very little in the 150 years since the stone statue of the giant was dug out of the ground and presented to the world as proof that colossi had once strode the earth. I thought of Barnum's fake-of-a-fake giant drawing crowds when I read Travis Saunders' piece, "Can we trust scientists who give TED talks?" at Science of Blogging. Like some of the writers who had to grudgingly concede the fakery of the giant, Saunders admits up front that he had enthusiastically written about the claims that divorce, obesity and other personal problems could be contagious. But now he writes:

The final thing that I find personally distressing about these issues is that I love listening to TED talks and reading books about big ideas. And to be honest I would love to be one of those people who gives those sorts of compelling talks that so clearly demonstrate why an idea or piece or research has meaning outside of the lab. It worries me that other people who share that goal seem to be spreading a message which may not actually represent the "truth" it makes me nervous about knowledge translation in general if those who are among the most successful are also those pushing the most questionable findings.

I find it distressing, too, and I understand the urge to want to be the next Malcolm Gladwell. It's this urge that has journalists and scientists constantly presenting Big Ideas in ever more colorful forms. And then there are the bandwagon jumpers who don't actually have the time or the background to fully research a topic but don't want to be left behind.

At the same time, many great journalists - and scientists acting as journalists - have made careers ignoring the Big Ideas and instead working their beats to share with the wider world legitimate scientific advancements that are important but not necessarily paradigm shifting. These writers tell us why a new study matters, and, by marking a trail through historical analogues and peer reviewed research, they show us the trends that we have not been able to see for ourselves.

Just in the past few months, Ron Winslow and John Carreyrou at The Wall Street Journal helped readers see how new research on costly stents for coronary artery disease might change the standard clinical approach to one of the world's deadliest illnesses. Marilyn Marchionne at the Associated Press explained the reasons one type of screening might be superior to another for preventing cervical cancer. And Gretchen Reynolds at The New York Times asked - and answered - a crucial question for millions of people with joint pain: "Do cortisone shots actually make things worse?"

I'm going to carve out some space on this blog each month to highlight a health science idea that you may never see in a TED talk but that might actually have a much bigger impact on your life and your readers' lives.

Let the nature fakers have the glory. To mix Teddy Roosevelt metaphors, let's turn our attention to the ideas that speak softly but carry a big stick.

Photo credit: Suzie Katz via Flickr