Dozens of injured patients die from preventable blood loss each day. Here’s how we uncovered this health crisis

Image by Ahmad Ardity via Pixabay

Inside a lecture hall in San Antonio filled with medical students, I listened as a group of seasoned trauma surgeons described a preventable problem that was killing many of their patients.

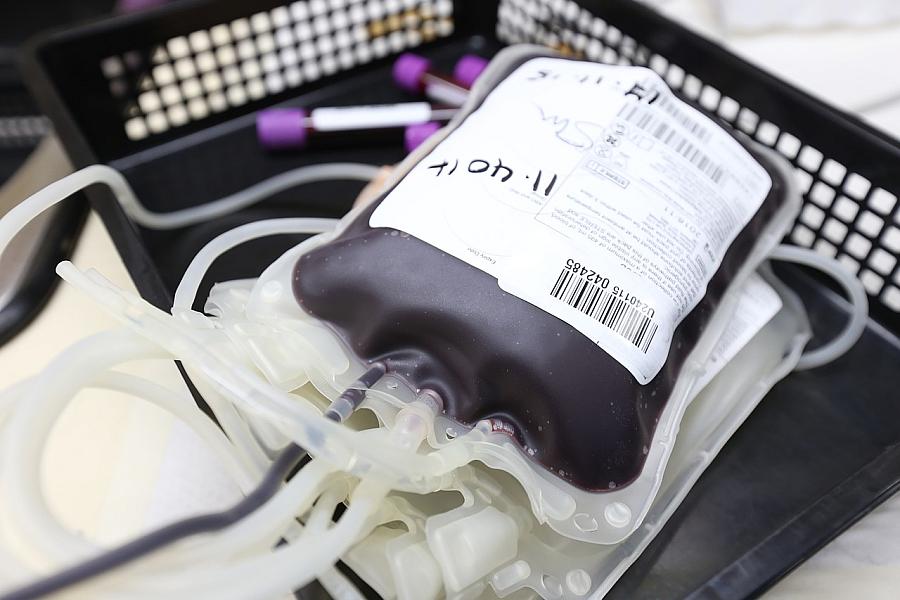

Every day, trauma victims succumbed to injuries they might have survived, had they not bled to death first. For hemorrhaging patients, time simply wasn’t on their side. Their risk of death increased with every minute they did not receive emergency blood transfusions and other crucial treatments.

A tenet of trauma medicine — that patients should be treated within the “golden hour” immediately following a major injury — simply did not apply to those with major bleeding, said Dr. Susannah Nicholson, then a professor of trauma and emergency surgery at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“It’s really more like a platinum 15 minutes,” she told the students, who were gathered for a gun violence symposium hosted by the medical school. “We need to be able to address the problem in a much earlier time frame. This emphasizes the need to develop therapies to increase that window of survival in the prehospital environment.”

In other words, these patients could have survived. Our health care system was just too slow to save them.

But solutions were out there, noted another speaker, Dr. Donald Jenkins, a faculty physician and retired Air Force surgeon. The previous year, he had worked with the local blood bank and area emergency medical service providers to launch a unique program that stationed blood on ambulances and helicopters across San Antonio and South Texas. It made lifesaving transfusions available much sooner to bleeding patients who could not wait until they got to a hospital.

The more I listened to this group of passionate physicians that afternoon in October 2019, the more I became convinced that I had stumbled across something big. That day, I learned that traumatic injuries — not only from guns, but also from cars, falls and other incidents — collectively killed more children and adults under age 45 than any other cause. Together, they were the single largest factor stealing years of potential life from Americans.

This was a preventable health crisis that elected officials had neglected for years.

That lecture sparked the most ambitious reporting project of my career — a national investigation, in partnership with the USC Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, of an epidemic that needlessly kills tens of thousands of Americans every year. Four years later, my six-part series, “Bleeding Out,” was published in The Dallas Morning News and the San Antonio Express-News, the news outlets where I started and finished my reporting.

Here’s what I learned:

Beat reporting yields impactful investigations. When I began reporting on preventable trauma deaths, I was the medical reporter at the San Antonio Express-News. I attended the symposium without giving it much thought — it seemed interesting and I was not on deadline that day. I figured that I would emerge with a new story idea or cultivate some new sources. Instead, a much bigger story fell into my lap.

Don’t give up on a good idea. I was a few months into my reporting when the COVID-19 pandemic became my primary beat. For a year and a half, I had to set aside this project and several others. I kept a pulse on it by staying in touch with my sources and doing stories on how the pandemic had led to historic blood shortages. In the fall of 2021, I was finally able to give the project my full attention.

Report backwards. Big investigations often start with a problem, with reporters learning about potential solutions along the way. In this case, my initial focus was entirely on the solution — the South Texas prehospital blood program that was already saving lives. Before leaving the Express-News, I interviewed about 30 sources, including the trauma surgeons, blood bankers, and paramedics who had helped make the program such a success. I also spent more than 40 hours shadowing San Antonio Fire Department paramedics as they responded to trauma calls and administered blood in the field. Had I stopped there, I would have ended up with a strong explanatory story, but nothing more.

Once I got to Dallas, I was forced to consider how this problem applied to other parts of Texas and the rest of the country. Blood loss is a national problem that afflicts major cities, suburbs and rural areas. If San Antonio’s trauma system was doing something right, then maybe other places were doing things wrong. As I broadened my focus, I talked to experts across the country and consulted medical journals. It became clear that this was a preventable health crisis. Science-based solutions were already documented. Federal officials had known about this issue for a long time. Yet action was lacking.

Don’t be afraid of delving into complex medical research. Reading medical literature can be intimidating and confusing. There’s a big learning curve: randomized controlled trials versus observational studies, the difference between prospective and retrospective research, understanding statistical significance and study limitations. The pandemic had also highlighted that not all published research is created equal. However, medical literature proved to be invaluable in understanding the science behind this problem and its potential solutions. I immersed myself in medical journals, reading 285 articles that informed my journalistic findings.

That research armed me with staggering statistics. One article estimated that preventable blood loss killed 31,000 injured Americans every year, highlighting the urgency of the crisis. It gave me a strong grounding in the history of this area of medicine, allowing me to trace the field’s successes and failures in treating these patients over time. And it helped me speak my sources’ language and engage with them on technical subject matter in interviews. By doing my homework and asking informed questions, I gained their trust. That later helped me gain access to sensitive health care environments, including ambulances and trauma bays, for observational reporting.

This intimate understanding of trauma medicine also led to a collaboration with a researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who had studied inequities in access to high-level trauma care across the country.

Challenge experts’ preconceived notions. In big cities, emergency medical providers have long prioritized getting the most seriously injured patients to the hospital as fast as possible. The prevailing wisdom was to minimize prehospital interventions that would slow down paramedics. Many EMS providers, including in Dallas, argued that relatively short transport times negated the need for prehospital blood transfusions.

But I knew from my reporting and the medical literature that for patients with the most serious bleeding, that approach wasn’t good enough. Most patients with severe internal bleeding in the torso die around the 30-minute mark. Mortality rates for hemorrhaging patients have not improved in years. Studies have demonstrated that, no matter how fast hemorrhaging patients are treated once they get to the hospital, it isn’t fast enough. Too many patients are dying under the current system.

That information, along with anecdotes from San Antonio, New Orleans and other cities with successful blood programs, gave me the tools to push back against experts who argued for maintaining the status quo. In the end, repeated rounds of questions about a mismatch between current practices for bleeding patients in North Texas and the available medical evidence helped put pressure on local EMS leaders to act. In response to questions from The Dallas Morning News, Dallas Fire-Rescue, which provides emergency medical care to the city of Dallas, said it intended to launch a pilot blood program in 2024 — a change that will have an enormous impact on the type of care that bleeding patients receive.