Excerpt: Fighting viral misinformation takes more than facts — it requires history

Viruses rarely travel alone. Infection spreads alongside myths, rumors and stories about disease. I saw this firsthand when I was an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service, deployed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to investigate contagion after contagion. A microbe was my main focus, but the microbe’s spread was fueled by misinformation and disinformation. Falsehoods could accelerate epidemics and make people vulnerable to disease and death.

I had to leave public health and go to journalism school to learn about the contagious nature of information. It was during that training, and later in a newsroom and then a journalism fellowship, that I studied how information spreads from one person to another and why we fall for false information, especially during epidemics. Heightened fear and anxiety can be exploited when our ability to assess risk and make rational decisions is diminished.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the potential of false information to unravel scientific achievements and public health interventions designed to keep us safe. The virus is new but this problem is not. The antidote to belief in false information is not more information. Throwing facts at a person could make them feel even more strongly about their beliefs. It turns out that absent an understanding of why and how a person came to believe what they believe, it can be almost impossible to shift their attitudes and behavior.

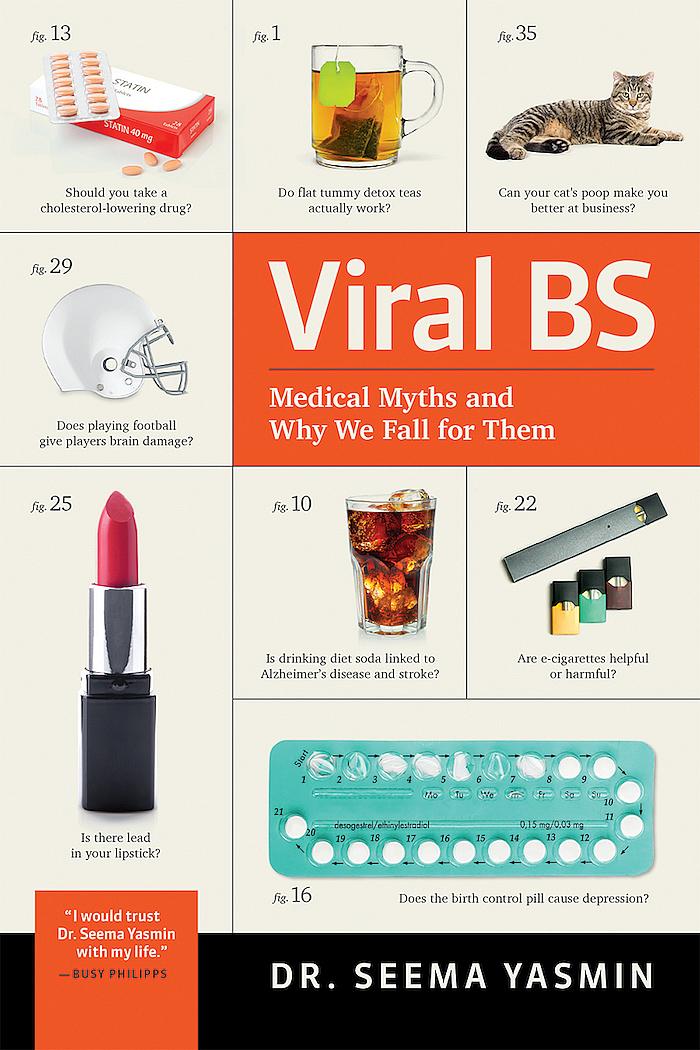

It was a look back at my own upbringing that helped me understand why we believe the things we believe and how we might start shifting long-standing ideologies. It’s why I started my new book, “Viral BS: Medical Myths and Why We Fall for Them,” with an admission of my own conspiracy theory-laden childhood. Here’s an excerpt:

The official maps we studied in school were made up, the cassette tapes told us. Europeans had fudged the way we looked at the world and our home countries. Geert de Kremer, a sixteenth-century Flemish man, better known as Mercator, had drawn a map that shrank India and Africa and beefed up Europe. It was a conspiracy. But we had our stories. Stories that helped us band together against these travesties, to counter the narratives that made us small and them big. There was safety in numbers, and we found unity and relief in our collective beliefs.

So, years later, when I was 27, a newly qualified doctor working in east London, I was sympathetic to the pregnant young woman rolling her eyes, crossing her arms, and refusing my prescription. I was working in my local hospital, walking distance from my home, where many of my patients looked like me: young, brown, daughters of immigrants. They too had been raised on conspiracy theories about the government, the Queen, doctors.

“I don’t want your antibiotics cuz they’re poison,” the young woman said, pulling the flimsy hospital sheet over her chest and kissing her teeth. Her sister in-law had run a car over her feet during an argument, and an infection was setting in to her bloodied toes.

“I know you’re worried about the baby,” I said. “But this antibiotic is safe for both of you.”

She didn’t believe me. Medicines were multinational drug companies’ way of controlling people of color, she said. They were tested on the poor and the voiceless to rake in profits for fat-cat CEOs. She wasn’t the only person rejecting my interventions. Pregnant women refused ultrasounds believing the sonic waves would harm their baby’s brain and heart. Fathers refused to vaccinate their toddlers.

A few years later when I was working as a public health doctor in the United States, one of the biggest tuberculosis outbreaks in the country’s recent history spread through the city of Marion in Alabama. The TB rate in Marion was 100 times the national average and most of the people affected were black Americans. Some Marion residents refused to get tested for the infection even when public health officials offered $20 as an incentive. The officials and doctors grumbled about the small numbers of Marion residents trickling in for blood tests and x-rays.

The doctors were ignoring history. A two-hour drive from Marion is Tuskegee, the site of a torturous, unethical medical experiment, conducted by government doctors on black men from the 1930s to the 1970s. Even those residents of Marion who weren’t alive when the experiment ended said that, because of those experiments, a distrust of medicine and doctors had been passed down generations like an old family Bible.

These stories shouldn’t be ignored. There is a bloody history packed into each aspirin pill: a story of Nazi concentration camps and Holocaust survivors. There is a scandalous story behind the discovery of penicillin and its uses—and I’m not talking about the stories you learned in school about mold and petri dishes and Alexander Fleming.

These stories, and so many others like them, are buried like dirty laundry considered too filthy to even try and wash. But their legacy lingers. We’d rather not wash our dirty linens because confronting the past raises difficult questions, like why would doctors inject bacteria into people’s spines, and why would scientists not treat syphilis patients with medicine?

The true stories we bury sprout fake stories, like fungi blooming from dead tree trunks. There is sometimes an inkling of truth in a conspiracy theory, and these truths wrapped in history and suspicion can spread faster than microbes, infecting people with a deeper distrust of doctors and science. History is the kerosene that ignites conspiracy theories and fuels new hoaxes.

Anti-mask and anti-vaccine messages spread during the pandemic convey more than false information about the science of masks and vaccines. Some of these messages propagate the claim that wearing a mask and getting vaccinated go against the ideals of “American freedom,” that masks and vaccines are in opposition to “the American way of life.” Shifting those beliefs requires more than listing scientific facts or repeating “believe in science.” It requires understanding historical legacies of polarization and anti-science movements.

**