Exploring disparities in diabetes among Latinos

Diabetes rates are soaring across the nation. But in Rhode Island, the Hispanic population has seen the most dramatic increase of any other group over the past few years.

It’s putting stress on patients, families, and health care providers. Over the next few weeks, we’ll explore what’s behind this sharp rise on our weekly health care feature, The Pulse. We begin with what health care experts believe may be one driver: many Latinos lack health insurance.

Lucia arrived in Rhode Island from Guatemala seven years ago. Today, she works in a clam factory, clearing a moving conveyor belt of broken shells. She gets health care at Clinica Esperanza, the free clinic for Rhode Islanders without insurance or who can’t afford health care. And a nurse has just referred her to an eight-week class called Vida Sana, or Healthy Living. We’re not using Lucia’s last name because she’s undocumented.

“Voy a dar la vuelta?”

“Si”

A nurse takes her around the corner to take some blood samples and interview her about her health.

“Voy a listar me para serte la sangre. Te va a ser el cholesterol, te va a ser cuanto esta tu conteo en A1C para saber si usted esta con diabetes o no diabetes.”

Nurse Luz Bettancourt asks which finger she wants to use for a quick prick, and tells her--with a wink–not to cry.

“Cual dedito quiere? Sin llorarme, ok? Respíreme uno, dos, tres."

Bettancourt drops the blood onto a slide, and slips it into a machine that checks blood sugar levels. The goal, to find out if Lucia is diabetic or on the verge of developing it. Lucia says she knows she needs to take better care of herself – and that’s why she’s come to this class.

“Para venir escuchar pues que es lo que puede comer uno de la vida sana, porque, porque veni aquí, por escuchar esto.” (Translation: "To come and listen to what it is you can eat for a healthy life, that’s why I came here, to hear that.

She pauses and smiles. What I really like to eat, she says, is beans with cheese, a little rice, pasta. But those starchy foods can contribute to high blood sugar. The machine starts checking Lucia’s blood.

She waits a few minutes for the results. And then:

“Esta lista para el resultado. Quiero decirle que usted debe ponerle mucha atencion a este clase.”

'Are you ready for the results?' asks Bettancourt. I want to tell you, you should really pay attention in this class.

“Usted sale con 11.9. Es muy alto. Tiene que mejorar mucho su comida.”

You’ve come out with 11.9, she says. That’s very high. You have to improve your diet.

Bettancourt explains the numbers, using a graphic ruler that goes from green to red, showing healthy to unhealthy blood sugar levels.

“Cuando esta casi en el siete, te esta diciendo que es pre-diabetica. Pero usted no esta en el siete ni en esto, usted es mas alla de alla. Usted mas del—usted esta aquí arriba, casi aca, mire. Llego al 11. Quiero decir que usted se ha pasado toda esta área, usted esta en la alerta ya. Demaciado alta.”

(Trans: "When you’re almost at seven, it’s telling you you’re pre-diabetic. But you aren’t at seven, or even here. You’re much higher than that. You’re almost up here, at 11. It means you’ve passed all of this area; your levels are at high risk – too high.")

Bettancourt counsels her to eat more fruits and vegetables, to get some exercise. Then she sends her back to the classroom with her paperwork.

For many new participants in the Vida Sana class, the news is the same – they’re diabetic or at high risk of becoming diabetic and didn’t know it. Bettancourt ushers in the next patient, and the first class of Vida Sana gets underway.

“The prevalence of diabetes has grown across the United States in the past 20 years or so.

This is Dora Dumont, an epidemiologist with the Rhode Island Department of Health. She says that as our collective weight has gone up, so have rates of diabetes. Obesity, a lack of exercise, and a poor diet are all risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes. That’s the type where you can’t make enough insulin to keep your blood sugar at normal levels. It’s a chronic disease that can wreak havoc on the body if it isn’t managed. And it’s one that more of us are dealing with every day, says Dumont.

"And in fact when we look at the Rhode Island data, pretty much across the board, a lot more adults have diabetes than did 15 years ago.”

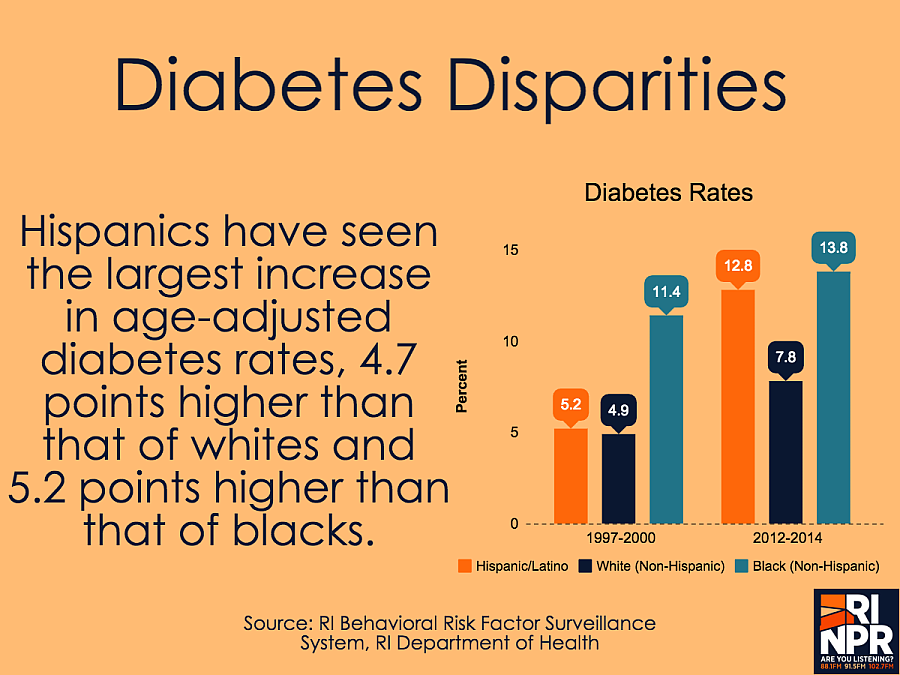

But Dumont has uncovered new data showing that rates of diabetes have risen steeply among Hispanics in the Ocean State. She’s also found that the disparities between them and other demographics have widened. 15 years ago, she said, about five percent of Hispanics and whites had diabetes. But today:

“White adults in Rhode Island have an age adjusted rate of diabetes of just under eight percent, while Hispanics have an age adjusted rate of just under 13 percent.”

So what accounts for the disparity? I put the question to Dimaris Rosales. She helps run the Vida Sana program at Providence’s free clinic, for patients like Lucia can’t afford insurance. One of the main problems, she says, is that her patients can’t afford the kind of healthy food you need to control or avoid diabetes.

“If you go to supermarket and see it’s cheaper to buy the bad stuff than buy fruit and vegetables,”

Cultural factors play a role, too, she says.

“And sometimes they don’t know how to portion size. That’s one of the big issues we have as a Spanish person. When you go to eat they say your plate, you have to eat the whole plate. So we don’t have conscious of portion sizes. So what we do is we teach them how to eat. You have to like, choose the right portions.”

Rosales says the eight week class teaches participants what to eat, how much, even how to read labels in the supermarket. But if you already have diabetes, eating healthy food is just one challenge poor, uninsured Hispanics face. Affording medication is another. Rosales remembers one patient.

“He was in the program and we do the testing before they start the class. And his diabetes was out of control. When I ask him are you taking medication, he says no I don’t have the money to buy it. It’s insulin, and I have to pay $300 dollars for it and I don’t have the money. So we find out every time he feels sick he goes to the emergency room because they give him a little bottle of insulin for 15 days.”

Rosales says clinic staff raised money to help pay for the rest of the man’s insulin that month. But what about next month? Rosales isn’t sure what will happen. Rosales says education helps, and that by the end of the Vida Sana class, many participants have lowered their blood sugar. But they’re doing it against the odds, living in poverty.