Exploring the power of place

The power of place to shape health

At WHYY, I write about public health, policy and practice. After several years on the beat, I've learned that covering health more fully means paying more attention to how people's health is affected by where they live.

With support from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, that’s my plan.

When I go in for my annual check-up, the nurse asks if I smoke and how much I exercise. I fill out forms about which relatives have had cancer or a heart attack.

No doctor has ever asked me where I live.

The Pied Piper of geo-medicine, Bill Davenhall, thinks they should. Davenhall, a principal in the mapping company ESRI, argues that medical records should include geographic information--our place histories--alongside the rest of our vital statistics.

The triad of “genetics, lifestyle and environment” shapes health, but Davenhall and others say physicians, public health officials--and maybe health reporters--largely ignore the final piece of that health trinity.

“I don’t really think my physicians really get this part of the equation,” Davenhall said during his TedMed talk in 2009. “What does that really mean--my environment?”

Short answer: the places and spaces where we live, work and play.

Building the case

In recent years, a legion of health researchers has convinced funders--the federal government and private foundations--to back their investigations on place and health.

Policy wonks use the term “built environment” for the job sites, parks and neighborhoods where we spend time. And now, they are finding ways to inventory those environments to test a growing hunch that life chances, including health, are closely tied to where you live.

How closely? That’s still up for debate.

Public health pioneer Howard Frumkin, made the case in an editorial from 2005: “Poor people and people of color disproportionately live near these locations and suffer associated health consequences--the effects of diesel air pollution, noise, injury risks, and ugliness.”

The neighborhood effect

Philadelphia researcher Amy Hillier, whose work I reported on in 2009, was one of the first to introduce me to the notion that “neighborhood effects” can hurt health.

Hillier trained as a social worker and later carved out expertise in geographic information systems and mapping. Her team at the University of Pennsylvania surveyed outdoor advertising in five cities and found ads for “unhealthy” products—tobacco and sugary drinks--clustered in black and Latino communities.

“Our likelihood of being overweight or obese, our likelihood to consume alcohol or to smoke cigarettes, to buy Kentucky Fried Chicken, these are all spatial issues that we think can affect people's health as well,” Hillier said.

Emerging research on the built environment is drawing both converts and skeptics. In April, the doubters gained traction when a pair of studies challenged a long-held--and well-financed--tenet among the believers. The findings, in separate studies from the Public Policy Institute of California and the RAND Corporation, question the idea that poor, urban neighborhoods lack affordable and nutritious food options and that these “food deserts” drive higher rates of obesity.

Designs on better health

Some health advocates worry that thoughtful planning and city design have been undervalued in public health. If so, that may be changing.

Health officials now regularly invite colleagues from land-use, urban design, and transportation to join them as they try to craft policies to improve neighborhood health. I’ll spend this reporting-year writing about attempts to design safe, healthy places across the Philadelphia region and hunt for innovative examples from other parts of the country.

Look for my stories on WHYY’s online home Newsworks.org. The project launches at the end of this year. We’re planning a multimedia and mapping series about efforts to overhaul the places where people work, play and live--as well as a community forum and lots of opportunities for civic dialogue.

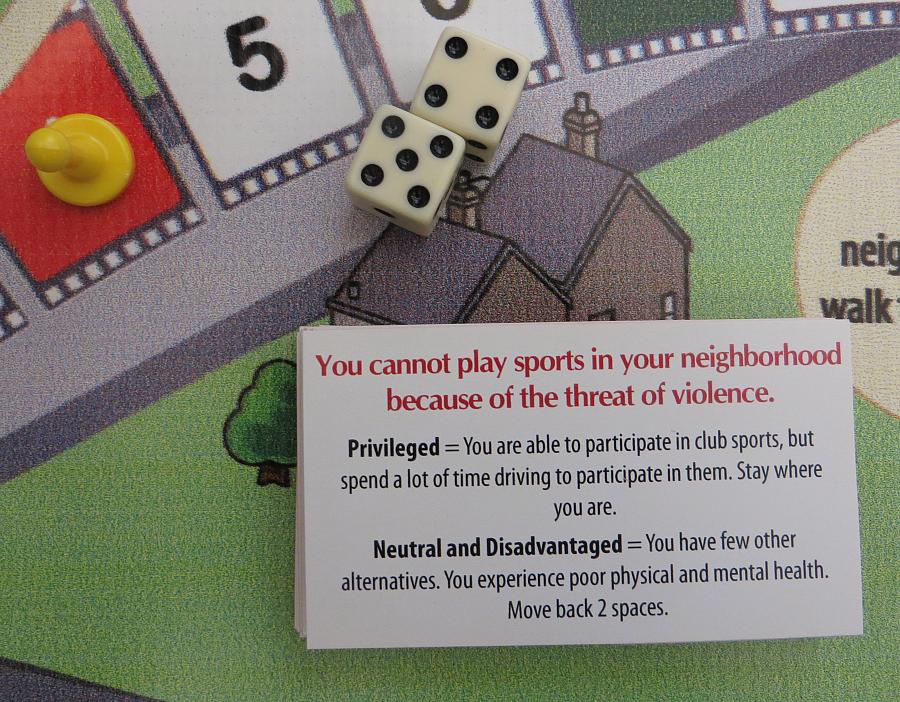

Photo credit: Taunya English

Photo caption: Game pieces from the Life Course Game developed by CityMatch. The game was designed to increase awareness about factors that can influence life chances.