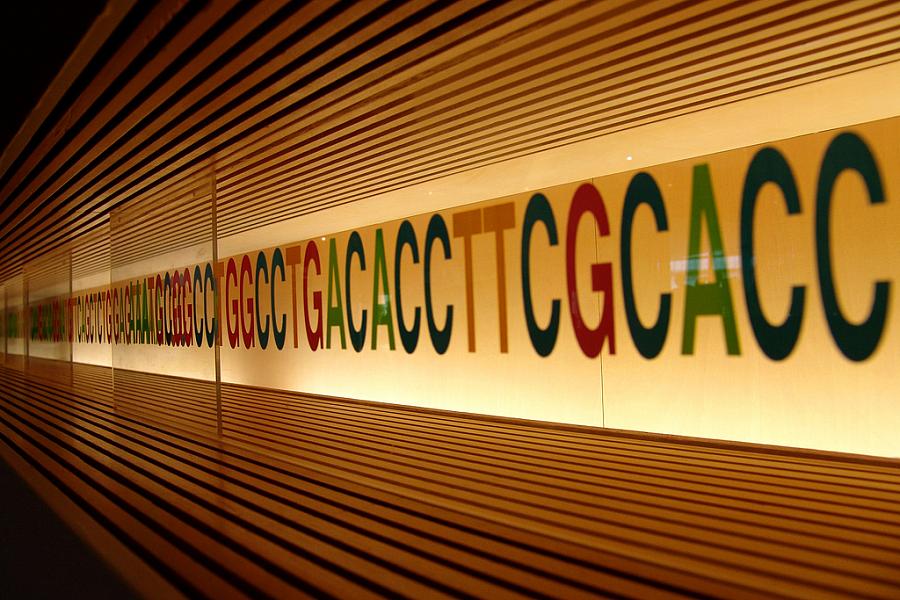

Family trauma shows up in kids’ DNA, study finds

One of the regular themes of this blog is that severe childhood stress and trauma can become biologically embedded in young bodies and minds, with health consequences that play out over a lifetime.

Previous research has shown that toxic stress can hijack a child’s hormone system and curtail regular brain development. And we know that childhood adversity correlates with a host of bad health outcomes. But new research published June 16 in the journal Pediatrics suggests that a child’s experience of traumatic family events can hit children at the most basic cellular level: the DNA in their chromosomes.

For the new study, researchers at Tulane University and the University of New Orleans recruited 80 children ranging in age from 5 to 15 from the New Orleans region. Caregivers were asked to report the kids’ exposure to family violence and disruption, and genetic samples were taken from each of the kids.

The goal of the study was to better understand how traumatic events experienced early translate into poorer physical health later in life. Past research has shown that the tips of chromosomes – bits of DNA known as telomeres – tend to be shorter in those who’ve endured sustained stress or trauma. Shorter telomeres, in turn, are linked to a host of chronic illnesses and accelerated aging.

In short, the New Orleans researchers found that the more violence and disruption a kid had witnessed, the shorter the length of telomeres. “Witnessing family violence exerted a particularly potent impact,” the study says.

Lead author Dr. Stacy S. Drury, director of Tulane’s Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Genetics Laboratory, described the study’s results in a release:

Family-level stressors, such as witnessing a family member get hurt, created an environment that affected the DNA within the cells of the children. The greater the number of exposures these kids had in life, the shorter their telomeres were – and this was after controlling for many other factors, including socioeconomic status, maternal education, parental age and the child’s age.

But here’s the surprising twist: Girls were significantly more likely to harbor shortened telomeres than boys. And for young boys with moms who’d reached higher education levels, the telomeres were longer on average, suggesting the better-educated moms wielded some kind of buffering effect.

“It does suggest that girls are much more impacted by negative events within the family than are boys,” Drury told The Times-Picayune. But it’s not yet clear why.

The usual caveat applies here: Both of those intriguing findings could be an artifact of sample size or selection, and it will take more than one study to pin down the ways in which gender or education complicate the story.

But the study does add to a growing body of research that offers a fascinating new glimpse into how our bodies manifest the stresses and hazards of our environment. UCSF molecular biologist Elizabeth Blackburn and colleagues did much of the early pioneering work on telomeres. Blackburn shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in medicine for her groundbreaking work in the field.

Telomeres protect the ends of chromosomes; the most popular metaphor compares them to the plastic casing that seals the ends of shoelaces. As we age, telomeres naturally grow shorter. A naturally occurring enzyme called telomerase serves to build them back up again, in a constant interplay between erosion and rebuilding. Think of a sandy beach: every year, heavy winter surf eats away the beach, carrying sand away, and every summer, gentler surf rebuilds the beachhead to its former fullness. But some experiences – debilitating stress, for example – can speed up “erosion” and overwhelm the rebuilding effect, leading to prematurely shortened telomeres.

In collaboration with UCSF psychologist Elissa Epel, Blackburn has published a number of innovative studies linking telomere length to environmental stressors, aging and illness. Telomere length has emerged as one potential barometer of a person’s overall health – and as a potential warning sign to take better care of oneself.

The New York Times described some of their research in a profile of Blackburn last year:

Compared with the mothers of healthy children, those with sick ones had shorter telomeres and less telomerase, and the longer they had been caring for the children, the shorter their telomeres were. The findings were similar in people taking care of spouses with dementia. Other studies have suggested that traumatic events early in life may have effects on telomeres and health that persist for decades.

We’ve long known that children who witness strife and violence are at higher risk of mental health problems and addiction as they grow up. But the new research from Tulane suggests that it’s not just our minds that are imperiled; the most basic building blocks of cellular life are somehow registering our traumas and possibly shrinking as a result.

More studies are needed to flesh out the links, and the research on telomeres and their link to aging and health is still a young field, but one that’s very much worth following.

Photo by MIKI Yoshohito via Flickr.