Giving To Get: Could Organ and Tissue Donors Become Less Selfless?

Summer is coming and with it the occasional scene of children sitting at folding tables selling lemonade.

Summer is coming and with it the occasional scene of children sitting at folding tables selling lemonade.

Imagine walking up to one of those tables, picking up a cup for a sip only to find it filled with human blood. (Forgive me the imagery. I'm under the influence of late night readings of Christopher Farnsworth's latest vampire novel, Red, White and Blood.)

Most of you will think that selling blood would be disgusting and illegal. Were the lemonade stand moved inside a clinic and the girls given licenses in phlebotomy, though, many of you would change your minds. How can I know that? That long held belief – codified in federal and state laws – that we should not be allowed to buy or sell pieces of our own bodies is changing.

In December 2011, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that bone marrow donors could be paid for their donation. The judges said, in part, that plasma donors already are compensated, so bone marrow donors are just the next logical step.

Expect more steps to follow.

The lawsuit that led to the decision was brought by the libertarian law organization The Institute for Justice. And the decision was immediately hailed by Ilya Shapiro at the libertarian Cato Institute, who predicted that the decision would pave the way for the buying and selling of organ transplants:

The good news is that, with the bone marrow market effectively deregulated, Congress may now be motivated to reexamine its misguided ban on compensating organ donors. One of the greatest obstacles to reforming the prohibition on organ sales is the fortunate fact that relatively few Americans require organ transplants in any given election cycle. According to government statistics, 112,546 Americans are currently on some kind of organ transplant waiting list. That means only around 1 in 3,000 Americans (and their families and friends) would be seriously motivated to demand organ transplant reform from Congress. Congress will now be forced to grapple with its policies regarding bone marrow transplants, which may be an opportune time for advocates to push for wider organ transplant reform.

Remember, this bone marrow decision was made by the San Francisco-based Ninth Circuit Court, commonly referred to by conservative critics as "the nutty Ninth" and "the Ninth Circus". When you have libertarians excited about a decision coming out of the Ninth Circuit, you are witnessing a cultural change. Five years from now, the debate about compensating people for donating organs and tissue may be over and, instead, we may be debating who should cover the costs.

And compensation can take many different forms.

Debbie Stevens was hired by a company in Long Island, New York, after she told a company executive who was on the waiting list for a kidney that she would donate her kidney to the cause. Stevens donated her kidney in a donation chain similar to the one described in February 2012 by Kevin Sack in The New York Times. She donated to a stranger so that her boss could be moved up the waiting list.

After the donation, though, Stevens was fired. Now Stevens has filed a complaint with New York State Human Rights Commission and is preparing to sue.

What if Stevens had been paid outright for her donation instead of hired under the presumption that she would donate her kidney? Would she still have grounds to sue? And would anyone be sympathetic to her case now?

I've been a registered organ donor since I first was licensed to drive, and I've been a member of the National Marrow Donor Program's registry for more than 10 years. (Facebook has just made it easier for people to become registered organ donors and to share their status.)

But I still get squeamish when people start talking about paying donors for organs and tissues. We already have for-profit companies making money off products derived from human tissues, and that has led to infection outbreaks, ethical breaches, and shortages of life-saving treatments. I'm not sure that paying donors will make the transplant system more fair or efficient. As Stevens' case suggests, it may just open up new opportunities for people to be exploited.

I think I'm in a shrinking minority, though.

You can see the basic assumptions about what is ethically acceptable in the transplant arena starting to shift in part by reading the comments people post below stories on the topic. Kevin Sack's kidney chain piece garnered more than 200 comments before the Times closed the comments section.

Almost all of them lauded the story like this: "Amid so many stories of man's inhumanity, such a contrasting spirit of a shared spirit of community among far-flung 'strangers' is pure antidote." And a few even suggested that paying for organs would be a good move: "Impressive record, but maybe all this hoop-jumping wouldn't be necessary if we legalized paying organ donors."

By contrast, Michael Smith's stunning investigative piece for Bloomberg, Desperate Americans Buy Kidneys From Peru Poor in Fatal Trade, has zero comments nearly a year after publication.

"The poor have become a spare-parts bank for the well-to- do," University of California, Berkeley, anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes told Smith.

Do the well-to-do or even the OK-to-do care? I've seen no major fuss being made about the bone marrow transplant decision, and I am doubtful an attempt to allow people to be paid for organ donations would cause much of an uproar either. But does that make it right?

Let me know in the comments below. You can also send me a note at askantidote@gmail.com or via Twitter @wheisel.

Related Content:

Live Organ Donations: Not Always Heartwarming Human Interest Stories

Organ donation for Latinos isn't only a medical issue

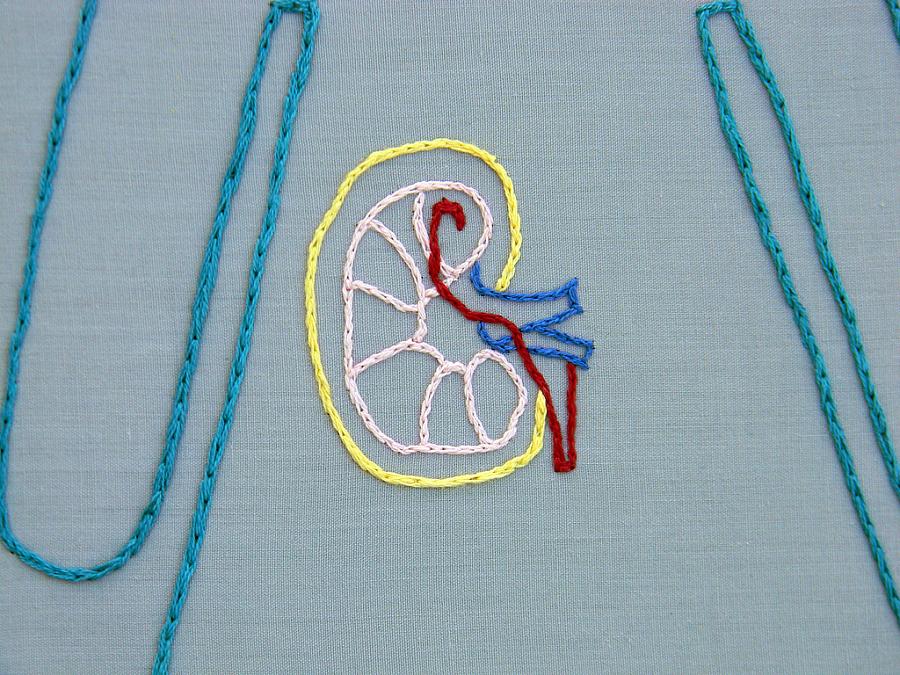

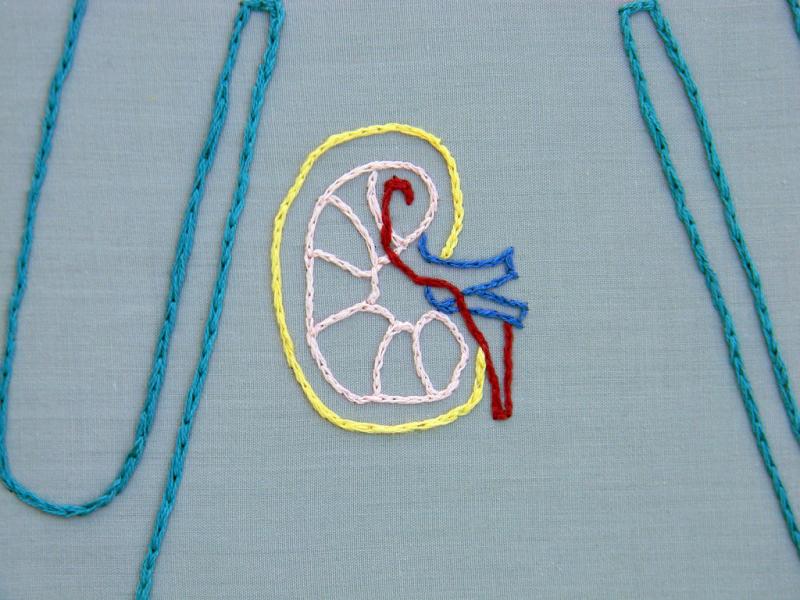

Photo credit: spectacles via Flickr