The Health Divide: $600 million donation will support med schools at HBCUs; Native communities denied federal health data

(Photo by Getty Images)

Bloomberg Philanthropies announced major donations to medical schools at four historically Black colleges and universities last week.

Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, Meharry Medical College in Nashville, and Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles will collectively receive a total of $600 million. Bloomberg is also supporting establishment of a new medical school at another HBCU, Xavier University School of Louisiana in New Orleans, with an additional $5 million gift.

“This investment will directly improve the pipeline for Black physicians and help to close the health care disparity gap,” said Dr. Yolanda Lawson, president of the National Medical Association, in a statement.

The support is especially important because the Supreme Court recently disallowed affirmative action in university admissions, as Lawson told Thalia Beaty at AP News. The change has led mainstream medical schools to make extra efforts to recruit students of color, reports Lauren Sausser at KFF Health News.

While the recipients of Bloomberg’s generosity are historically underfunded medical schools, they educate almost half of Black doctors, report Todd A. Price and Eduardo Cuevas at USA Today.

The investment comes amid ongoing challenges to diversify the nation’s physician workforce. For example, Black residents leave their training programs, or are forced out, at higher rates than white physicians-in-training.

Overall, fewer than 6% of U.S. doctors are Black, compared to 13% of the U.S. population.

This has major implications for Black health care, as explored by a Center for Health Journalism webinar in 2023. It’s a big part of the reason that many Black patients don’t trust their physicians, and that Black people die younger than whites overall, writes Benjamin Chrisinger, a Tufts University professor of community health, at The Conversation.

A 2023 study found that even a single Black doctor in a county was associated with longer life expectancy for Black residents there.

Black nurses can also help improve health care for patients of color. But nurses, too, face racism on the job, and fewer than 7% of nurses are Black.

A nationwide nursing shortage — attributed to low pay, high caseloads and lingering pandemic burnout — has implications for Black health, reports Jennifer Porter Gore at Word in Black.

“Experts say the situation will exacerbate the lack of access to care for communities of color, increase the time it will take to get routine as well as urgent or specialized medical attention and further widen the health gap between Black and white patients,” Gore writes.

In response, nurse education programs are offering accelerated training, and the federal Health Resources and Services Administration is investing $100 million in nurse training.

HBCUs are also big players in nursing training, educating almost 7% of the nation’s graduate nurses.

The lack of Black medical providers is a longstanding problem, spotlighted more than 20 years ago in the landmark 2003 “Unequal Treatment” report by the Institute of Medicine.

Bloomberg’s donations will bolster the endowments of selected medical schools, potentially reducing financial strain for the institutions and allowing for more spending, Beaty reports.

Native American communities denied federal health data

Disease investigators and public health workers in Native American communities say they’re not getting the health data they’re supposed to, reports Jazmin Orozco Rodriguez at KFF Health News.

“We’re being blinded,” said Meghan Curry O’Connell, chief public health officer for the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board.

The Indian Health Care Improvement Act, reauthorized in 2010, guaranteed access to data that the Department of Health and Human Services regularly shares with state and local authorities. But tribal health officials report that their access has frequently been denied.

For example, a lack of data on COVID-19’s spread impeded contact tracing during the pandemic. Workers at the Great Plains Tribal Epidemiology Center wasted more than a years’ worth of time collecting and collating data on their own, said the center’s lead epidemiologist Sarah Shewbrooks.

During the early pandemic, the COVID infection rate among American Indians and Alaska Natives was more than triple that of non-Hispanic whites.

The problems can arise from confusion over policies to share sensitive data on topics such as HIV and drug use. Sometimes federal agencies failed to recognize tribal epidemiology centers as public health authorities, forcing the tribes to take roundabout routes, such as requesting data via the Freedom of Information Act.

In 2022, in the wake of a U.S. Government Accountability Office report that confirmed tribes’ concerns, the Department of Health and Human Services consulted with tribes and updated its policies.

The situation has improved since, but problems remain, KFF reports.

Has the rise in U.S. maternal mortality been exaggerated?

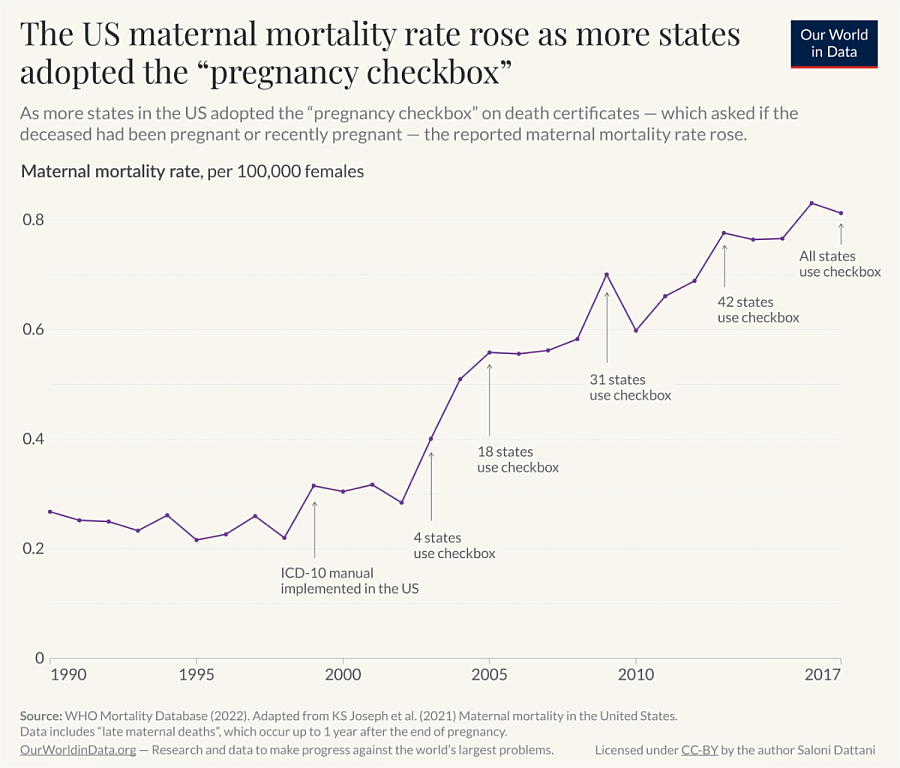

A number of outlets have reported on a rise in deaths among U.S. pregnant and postpartum women since 1999 — but that reported increase may be due to changes in the way deaths are classified, reports Jerusalem Demsas at The Atlantic.

Saloni Dattani, a researcher at the nonprofit publication Our World in Data, explained to Demsas that a gradual change in how maternal deaths were recorded underlies the apparent rise.

Recording the cause of death for death certificates can be tricky. For example, if a woman with cancer pauses her chemotherapy when she becomes pregnant but subsequently dies, is the pregnancy or the cancer the primary cause?

The International Classification of Diseases guidelines changed in 1994, expanding “maternal death” to include any demise during pregnancy, childbirth, or the first six weeks postpartum. It recommended a checkbox for pregnancy on death certificates to ensure maternal deaths would be counted.

This checkbox was added by U.S. states, a few at a time, between 2003 and 2017. As this happened, recorded maternal death numbers rose, creating an apparent trend.

Dattani isn’t the only scholar to notice the issue. In March, Vox reported on a study in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology (AJOG) that also attributed the apparent rise to the pregnancy checkbox and the way it misclassified some deaths that weren’t truly maternity-related.

“Most experts agree with Dattani’s conclusion,” Vox’s Anna North wrote in July.

The CDC has acknowledged how the checkbox changed maternal mortality tracking, but deaths still rose after all states had adopted the checkbox. COVID’s dangers for pregnant people may also have contributed to a rise.

And the CDC has disputed the AJOG results, suggesting the study’s methods, which ignored the checkbox, could lead to an undercount of maternal deaths. The authors acknowledged this could have happened.

Many deaths that had the pregnancy box checked were mistakes, the CDC says, with dozens of deaths checked as pregnancy-linked for deaths of people older than 65, as ProPublica noted in April.

All told, the nation seems to have transitioned from undercounting maternal deaths to overcounting them.

Dattani’s interpretation doesn’t mean the maternal death rate isn’t a problem; the AJOG data suggested the U.S. maternal death rate remains a bit above that of other developed nations.

“Many scholars agree that far too many people are dying during and after childbirth in the United States,” North wrote.

Even those who criticize the CDC’s numbers support ongoing efforts to support maternal health, such as better health care and paid parental leave, North reported.

And disparities persist. The higher rate of deaths among Black women than white women was present both before and after the change in death certification, Dattani emphasized. The AJOG study and CDC data also confirm the disparity.

From the Center for Health Journalism

- Webinar Aug. 27, 11:30 a.m.–12:30 p.m. PDT. “Would Project 2025 herald the end of health policy as we know it?” Project 2025 is a conservative governing plan from a right-wing think tank that seeks to drastically shrink the role of the federal government in American life. The implications for health care are huge. Former president and current candidate Donald Trump has distanced himself from the plan, but dozens of people working for him helped put Project 2025 together. What are Trump’s actual positions on health care? We'll seek fresh insights and explore story angles for local and national reporting with panelists Drew Altman, president & CEO of KFF; Victoria Knight, health care reporter for Axios; and Sarah Owermohle, Washington correspondent at STAT. Sign-up here!

What we’re reading

- “I feel dismissed’: People experiencing colorism say health system fails them,” by Chaseedaw Giles, KFF Health News

- “The infectious disease doctor shortage will hit marginalized people the hardest,” by Alia Sajani, STAT

- “Black people with Parkinson’s are underdiagnosed, miss treatment,” by Elizabeth Cohen, NBC News

- “Bystander CPR more likely to save your life if you’re white and male: Study,” by Dennis Thompson, HealthDay

- “Racism and discrimination lead to faster aging through brain network changes, new study finds,” by Negar Fani and Nathaniel Harnett, The Conversation

- “More than 40% of LGBTQ youth said they considered suicide in the past year, CDC report finds,” by Mary Kekatos, ABC News

- “Despite some gains, teens — especially girls — are struggling with their mental health since the pandemic, report shows,” by Brenda Goodman, CNN