The Health Divide: Chrystul Kizer’s story shows how young, Black girls are victims of human trafficking and justice system has been sent

Chrystul Kizer at a hearing in the Kenosha County Courthouse in 2019.

(Photo by Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Chrystul Kizer met Randy Volar in 2016 when he responded to an ad she placed on backpage.com seeking to exchange sex for money. Chrystul was 16. Volar was a 33-year-old white man.

She used the money from the encounter to buy food and school supplies. Although Volar knew Chrystul was underaged, he pursued her beyond their first encounter.

For her 17th birthday, Volar paid for her to Uber from Milwaukee to his home in Kenosha, 40 miles away. When she arrived, Volar surprised her with birthday cupcakes and introduced her to LSD, according to The Washington Post.

When Chrystul was arrested in a stolen car with her brother a few weeks later, Volar paid $400 to bail her out. After she was released, he forced her to have sex, and he recorded the incident. Over the next several months, Volar forced Chrystul to post sex ads to have sex with other men for money. He even drove her to hotels in Milwaukee for sex. Chrystul was a victim of human trafficking.

The recent widespread media coverage of her story highlights the extent to which young Black girls are denied recognition as survivors of sexual abuse, and instead are unjustly perceived as mature, aggressive perpetrators by a flawed criminal justice system.

On June 4, 2018, Chrystul’s life would change forever. After she got into an argument with her boyfriend in Milwaukee, she texted Volar for help. According to court records, Volar ordered an Uber to bring Chrystul to his home.

Before the Uber arrived, Chrystul put her boyfriend’s gun in her purse for protection. When she arrived at Volar’s home, he ordered a pizza and gave her LSD. Chrystul said the drugs made her “feel weird.”

Volar forced himself on Chrystul, and when she refused, he allegedly wrestled her to the floor to rape her. During the scuffle, Chrystul got to her purse, pulled out the .380 pistol, and shot Volar twice in the head.

She set his home on fire and fled the scene in his BMW. Chrystul was captured the next day and initially charged with arson and first-degree intentional homicide. Still, her defense argued she was legally allowed to kill him because he was sexually trafficking her. The prosecutor called the case premeditated and said Chrystul prostituted herself and killed Volar to steal his car.

In 2022, Chrystul achieved a legal victory when the state Supreme Court upheld a ruling that allowed her to argue self-defense under a state law protecting trafficking victims. She was released from prison in February on a $400,000 bond, thanks to money raised by many organizations. Chrystul fled the state, violating her bail conditions. She was captured two weeks later in Louisiana and returned to Wisconsin.

In August, Chrystul, now 24, was sentenced to 11 years in a Wisconsin state prison, followed by five years of supervised release, after pleading guilty to a lesser charge of second-degree reckless homicide in the killing of Volar.

Advocates for sex trafficked survivors hoped Chrystul would get time served. They argued that Chrystul, a person of limited financial means, was entrapped by an affluent man who was under investigation for a series of sexual assaults against young black girls around her age and younger at the time of his death.

Does race play a factor?

Chrystul’s lawyer, Larisa Benitez-Morgan, argued that Chrystul is “a victim of child trafficking, and her actions were not to the community as a whole, but rather a direct result of having been trafficked as a child.”

In Wisconsin, there are several state laws designed to protect victims of human trafficking who are under the age of 18. The 2011 law, known as Trafficking of a Child, makes trafficking a child a felony offense. The Wisconsin Safe Harbor Law, passed by the state in 2019, stipulates that individuals under the age of 18 cannot be prosecuted for engaging in prostitution. According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, there were 9,619 cases involving 16,999 victims identified in 2023.

Those who advocate for exploited children say Chrystul is a sex-trafficking survivor whose self-defense and survival were criminalized.

Girls of color who experience abuse are more likely to be funneled into the criminal justice system and regarded as perpetrators. In contrast, white girls who experience abuse are more likely to be seen as victims and are referred to the child welfare and mental health systems, according to researchers.

The adultification of African American girls, in which they are perceived as less innocent and deserving of help compared to their white counterparts, is another form of criminalizing self-defense, the report shows.

Randy Volar

(Kenosha County Sheriff's Office)

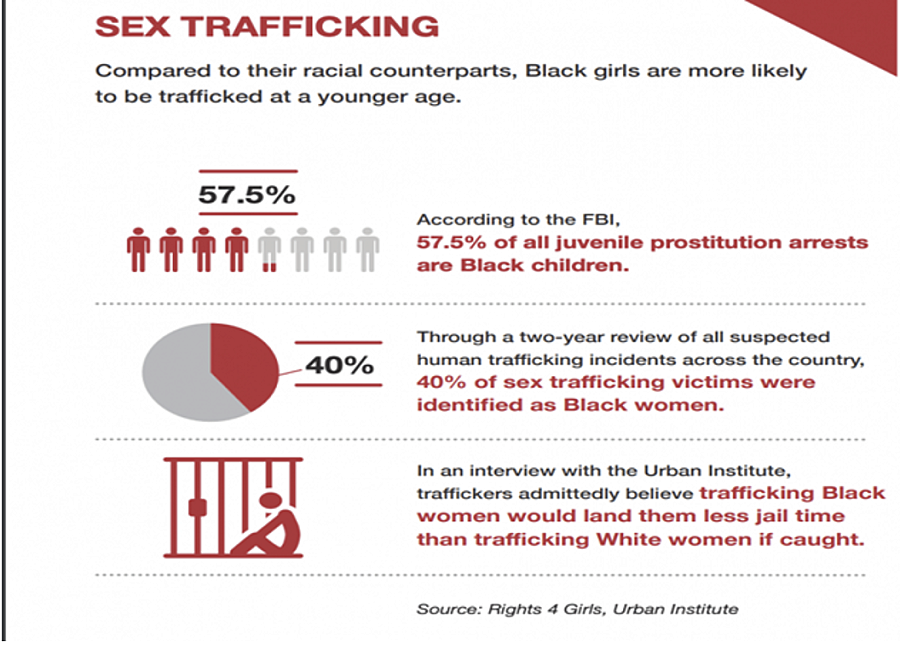

Before Chrystul’s trial, there was speculation about how race would influence the proceedings, since race plays a significant role in the sexual trafficking of Black girls. African American girls are overrepresented in trafficking statistics, even in communities where they represent a small portion of the population.

While Chrystul was abused and sold for sex by Volar, on Feb. 18, 2018, he was investigated by Kenosha Police after a 15-year-old girl called 911 to report that “a man was trying to kill her.”

That girl told police that she first met Volar at Milwaukee’s Juneteenth Day festival when she was 14, and he paid her $250 for sex. She spent a lot of time at his house, and while he usually gave her alcohol and marijuana, he gave her LSD for the first time, and it caused her to have a bad trip. When she was about to call the police, she said Volar went for a gun, and she ran out of his house.

In later interviews, the girl told police Volar searched websites for young girls and that he had numerous videos engaging in sex with underaged girls.

The next day police executed a search warrant and recovered hundreds of videos containing porn, needles, and drugs. At least one of the videos showed Volar having sex with Chrystul.

Volar was being investigated and potentially faced decades in prison on charges of sexual assault of a minor and child pornography at the time of his death.

Former trafficking victim speaks out

“When you see minors who are sex trafficked, you see a lot of adults who say ‘No, those are just fast kids. They are just promiscuous,’” said Cyntoia Brown-Long, who became a victim of sex trafficking and, at the age of 16, was arrested for killing a man who had solicited her for sex.

“There is definitely a stigma. You don’t view them as a victim,” Long previously said in an interview with AM to DM. Long was tried as an adult and sentenced to life in prison in 2006.

After being convicted of aggravated robbery and first-degree murder for killing 43-year-old real estate agent Johnny Allen, Brown-Long stated that she shot him because she believed he was reaching for a gun. Her case inspired state legislation in Tennessee to protect minors who are sex-trafficking victims.

Brown-Long’s 2019 memoir, “Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System,” was written while she was in prison. It documents her early years, and the 15 years she was incarcerated. Her case became national news in 2017 when celebrities like Rihanna and Kim Kardashian made the hashtag #FreeCyntoia go viral.

In August 2019, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam commuted her life sentence, citing “the extraordinary steps Ms. Brown has taken to rebuild her life.” While incarcerated, she earned her GED and college diploma while mentoring other young offenders, many of whom had been sexually trafficked.

Brown-Long’s childhood mirrors that of Chrystul Kizer.

Both grew up in poverty, experienced abuse and sexual assault, and both were raped and sexually trafficked by older, affluent white men. Child sex traffickers prey on already vulnerable children, and they convince them that they have no other options in life but to sell their bodies, and that no one else will want them.

These kids facing the legal system experience worse outcomes due to racism. They are often perceived as older and more mature than they are, garnering blame for their actions compared to white youth who are more likely to be seen as victims, Brown-Long said.

In Chrystul's case, advocates for sex-trafficked survivors question why Chrystul spent more time behind bars than Volar, who was arrested in February 2018 on charges of child enticement, using a computer to facilitate a child sex crime and second-degree sexual assault of a child.

Volar was released the same day.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to help achieve justice for victims of human trafficking. This includes continuing to tell their stories and providing a platform for them to speak out, as well as engaging with trafficking survivors. Additionally, reporters should find out what law enforcement agencies are doing to combat trafficking in their region, and if they don't have a clearly defined strategy, ask why. The root causes of trafficking — such as poverty, family breakdown, inadequate education, and community violence — require our full attention. Good journalism can highlight the best practices and consider ways to replicate them.

The cases of Chrystul Kiser and Cyntoia Brown-Long have drawn increased attention to the issue of human trafficking. But there remains thousands of individuals trafficked annually, the majority of whom are vulnerable Black girls who are targeted and exploited.