The Health Divide: Narcan vending machines are an effective tool in saving lives

A new vending machine in Brooklyn that disperses fentanyl test strips and naloxone. There are growing number of such machines in cities across the country, part of a broader effort to reduce the harms of drug use.

(Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Image)

Do you recall the anti-drug public service announcements from the 1990s featuring Rachael Leigh Cook?

Cook became the face of America’s anti-drug movement, thanks to her featured role in the “This is your brain on drugs” campaign. In one PSA, she held an egg and said, “This is your brain.” Then she picked up a skillet and said, “And this is heroin.” After smashing the egg with the skillet, she added, “And this is what your body goes through,” while the egg dripped all over the floor.

She smashes dishes, glasses, and a clock, proclaiming, "Your family goes through this.”

Cook concludes by asking, “Any questions?

Years later, both Cook and a number of Black activists have been vocal about the unjust and unfair effects of America’s war on drugs on the African American community. The war has resulted in widespread incarceration with minimal access to treatment, highlighting the systemic disparities and inequities within the criminal justice system.

In response to the increasing number of fentanyl-related overdose deaths, numerous states have adopted a proactive strategy. One such initiative is the installation of Narcan vending machines. According to a CNN analysis, 33 states have installed free vending machines to combat overdose deaths. Each state or city has its own machine placement and data collection protocol.

In August, Wisconsin’s Milwaukee County installed eight more harm reduction vending machines, bringing the total here to 19. Harm reduction vending machines provide an easily accessible method for people who use drugs to obtain a range of risk-reducing supplies and resources without many requirements for usage.

Wayne County in Detroit, Michigan, has installed 100 naloxone vending machines, an effort made possible by a partnership with Wayne State University's Center for Behavioral Health and Justice.

Similarly, Minneapolis, Minnesota, installed its first harm reduction vending machine in July after experiencing a surge in fentanyl-related overdose deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The vending machines hold harm-reduction supplies such as strips to test for fentanyl, nasal naloxone, pouches to deactivate medications, lock bags for medications, and gun locks. They also have packs to test for the particularly dangerous combination of fentanyl and xylazine.

A number of cities across the country have installed harm reduction vending machines, leading to questions about their effectiveness in saving lives.

A study in Cincinnati, Ohio revealed that a single vending machine directly reversed overdoses in at least 78 individuals during its first year of operation.

In Clark County, Nevada, after naloxone vending machines were installed, there were 229 opioid-involved overdose deaths in 12 months, compared to the predicted 270 deaths, suggesting that 41 deaths were prevented.

Black overdose deaths skyrocket

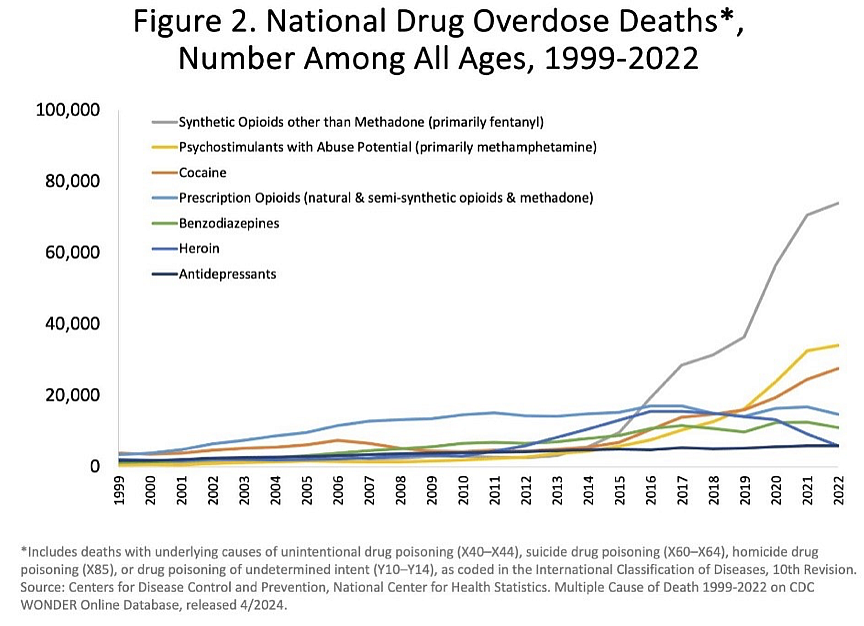

In 2022, there were a total of 107,941 reported drug overdose deaths, with 73,838 involving synthetic opioids, primarily driven by fentanyl.

There has been a dramatic rise in overdose deaths among communities of color in recent years. In 2020, the overdose death rate increased by 44% among African Americans and 39% among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals compared to 2019 — the most significant increases among the groups studied, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In comparison, the report revealed a 22% increase in overdose deaths among white individuals, the report said.

According to the CDC, the overdose death rate among Black men aged 65 and older was nearly seven times higher than that of their white peers in the same age group.

The report also highlighted an 86% increase in overdose deaths among Black individuals aged 15 to 24 compared to other age and racial groups from 2019 to 2020. And the study found that American Indian and Alaska Native women ages 25 to 44 had an overdose death rate nearly two times higher than that of white women in the same age range.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid commonly used to alleviate chronic severe pain or severe pain after surgery. It is like morphine but 100 times more potent. When combined with other illegal drugs, such as heroin, it can create more powerful and more dangerous substances.

My wife lost her uncle to a fentanyl overdose last year. He was a recreational drug user, and we are pretty sure he was unaware that the drugs he used were laced with fentanyl. The official cause of death was listed as an “accidental overdose related to fentanyl.”

Before COVID-19, White House officials were concerned about the increasing prevalence of opioids in Black communities.

Jerome Adams, U.S. Surgeon General during the Trump administration, told Politico in 2023: “The seesaw was already tipped to the wrong side. We were barely holding it up before the pandemic, and then it just completely tipped — particularly for communities of color.”

According to data from the CDC, between 2016 and 2021, the rate of fentanyl overdose deaths increased by 279% for all Americans. Although the total number of overdose deaths in the U.S. remained relatively stable in 2022, the escalating danger of fentanyl and the continuing racial disparities present a significant challenge for the Biden administration, which has made health equity a top priority.

Where do the two presidential candidates stand on the fentanyl crisis?

During a meeting with state attorneys general about the fentanyl crisis in July 2023, Vice President Kamala Harris said we must address the issue urgency and seriousness.

“One of the first steps that will be critical in ending this crisis in our country is treating substance abuse as the health care issue that it is and ensuring that we have an appropriate, well-resourced public health response to the underlying issue,” Harris said.

Former President Donald Trump told NBC News the following last September:

"(T)hey kill 250,000 people in the United States every year. … Their lives are destroyed. They’ve destroyed so many families. It comes through Mexico. Something’s got to be done. If we were in war, we wouldn’t lose 250,000 people. We’re losing more people than you lose in just about any war that we’ve ever had. And we lose them on a yearly basis. Something has to be done. And it has to be done fairly quickly.”

Are Milwaukee’s vending machines working?

In Milwaukee, harm reduction vending machines are free and easy to use. The machines are equipped with Narcan nasal spray, fentanyl test strips, medication lock bags, and gun locks.

(Photo by James Causey)

Since the initiative began last year, 17,000 products have been distributed through them.

The question is: Are these machines making a difference?

“Every overdose that is reversed or avoided due to the use of test strips or Narcan is not only another life saved but another opportunity for rehabilitation,” the Milwaukee Health Department said in a statement.

Milwaukee County has yet to study how many lives have been saved by its harm reduction vending machines. The goal is to place the machines closest to areas with the highest number of drug overdoses.

One key finding shows that in 2023, Black residents living alone had the highest count of overdoses at 2,232.

Under the location plan for the machines, 99.4% of those residents would have been within a 10-minute drive of overdose reversal supplies.

Milwaukee Interim Health Commissioner Tyler Weber emphasized that the city’s goal is to eradicate stigma around seeking help and provide essential resources without any prerequisites.

If we can do that, we can save lives.