The Health Divide: The public health story before COVID-19 has not gone away

Eric Anthony Richardson is removed from his home after a fatal fentanyl overdose.

Photo credit: James E. Causey

Think back. Way back to pre-COVID-19.

Do you remember the top news story?

Hint: it’s still a huge problem today that’s largely under-covered.

The opioid crisis may no longer dominate the headlines as it did before the pandemic, but it still claims tens of thousands of lives a year in this country and does not discriminate against race or class.

The losses touch countless people, including my family. On Oct. 3, 2022, my wife, Damia Causey, received a text from her mother. “I just found Eric dead in his room.”

Eric Anthony Richardson, Damia’s uncle, died in the home he shared with his mother. We discovered four months later that the leading cause of death was a fentanyl overdose.

Eric was only 55. He cared for my wife’s grandmother, his mother, for nearly two decades. He cooked her meals, made sure she took her medications, cleaned the house, and ensured she was safe.

The last time Damia saw her uncle, three days prior to his death, he was in good spirits.

He had no children and lived in a single-family home on Milwaukee’s north side.

Uncle Eric didn’t like taking many photos, and that’s the one thing that haunted my wife after he died.

“I don’t have any recent pictures with my uncle,” she told me through tears when I met her at his house.

Drug overdose deaths should not be sanitized. As journalists, we rarely see how traumatic they are. I’m sharing details so you can understand what families go through when they lose a loved one this way.

When I arrived at the scene, two police officers were outside and two other officers were inside. They were talking to my wife’s mother and grandmother. The officers were kind and offered their condolences. Though we saw Eric ourselves, it was still hard to accept.

Eric was slumped over in a kneeling position by his bed. He had been in that position for at least five hours. Some of his friends from the neighborhood stopped over to the house to comfort the family. Some wanted to see Eric for themselves. A few stepped into the bedroom and told their friend they loved him. Some cried. Some shared stories of how they had been friends for decades.

One of his best friends had seen Eric the night before and took his death extremely hard. He cried and said he wished it were him instead.

When the medical examiner’s office arrived to remove Eric, many of his friends lined up on the sidewalk outside to say goodbye. Neighbors whom he’s known since he was a child.

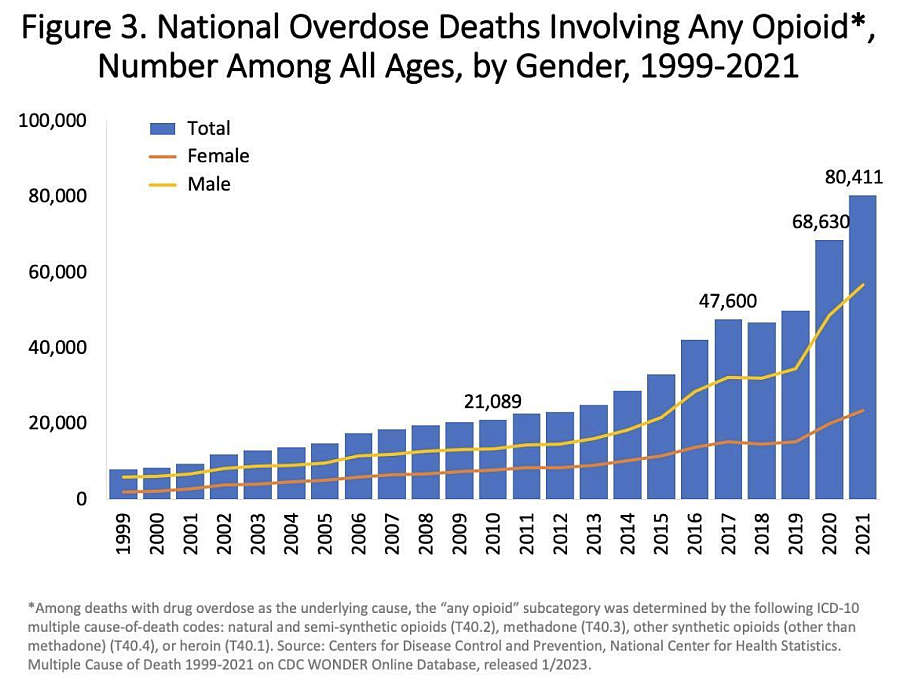

Deaths involving illicit drugs and prescription opioids have risen steadily since 2017, when the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared the problem a public health emergency.

The number of reported overdose deaths from opioids hit 68,000 in 2020 and rose by nearly 15% in 2021, to 80,000, the highest number recorded in a 12-month period, according to the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In Milwaukee County, as in other urban and rural communities, the opioid epidemic is making it all the more important to understand better the challenges associated with addiction and its public health implications. These deaths have exceeded injury-related deaths such as motor vehicle fatalities and homicides.

The numbers continue to increase. From April 1 to 3 this year, there were 17 fatal opioid overdoses reported in Milwaukee County. Four people who died from overdoses were homeless, and the average age of those who died was 50.

With the record-breaking death toll, some city leaders have declared the opioid epidemic a public health crisis.

According to Milwaukee Fire Chief Aaron Lipski, we must first de-stigmatize overdoses so people can get help.

“At its core, this is a mental health disease,” Lipski said.

We need to look at this epidemic much as we would look at someone with diabetes or high blood pressure. It’s no different than that. We must stop dumping on people because they are in a vicious cycle.

Eric didn’t go to the doctor. He was overweight. He was in pain. He liked to drink, and occasionally, he would smoke weed. I’m sure he didn’t mean to overdose, and I’m pretty sure he got the drugs from one of his friends.

In The Harvard Gazette in July, a reporter asked Jagpreet Chhatwal, director of the Institute for Technology Assessment at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, about interventions that appear to help with overdose deaths.

Chhatwal created a mathematical study to understand what can be done at the policy level to reduce opioid deaths, using simulation models for Massachusetts, Ohio, New York and Kentucky.

Based on the study’s findings, with widespread use of medication to treat opioid addiction and greater availability of naloxone, or Narcan, to reverse overdoses, deaths could decrease by 13% to 27% within two years and by as much as 46% within five years. The longer the interventions continued, the better the outcomes. The study was published in JAMA Network in June.

What hurt my wife and me the most about her uncle’s death was that we had Narcan and fentanyl test strips at home. My wife is a nursing student and received these items at a nurse fair to educate and potentially save others. Had she known her uncle was struggling, she said she would have given him the test strips to check drugs for fentanyl.

While Chhatwal’s study is promising, journalists must pressure leaders of cities to implement the necessary protocols to help decrease opioid deaths. Journalists must also go beyond the numbers to tell personal stories of those impacted by drug deaths.

While opioid deaths may not garner the headlines they did before COVID-19, journalists must keep telling these painful stories that affect us all.

What are the opioid death rates in your area?

What are officials doing to address the problem?

How much have the numbers increased?

Is it being treated as a public health crisis? Is the public health community being brought to the table for input?

We should ask these questions because the public sees the carnage left behind.

If your city or state doesn’t have a plan, questions need to be asked as to why.