Herd Immunity: If MRSA Lives in Houses, Go Knock on Its Door

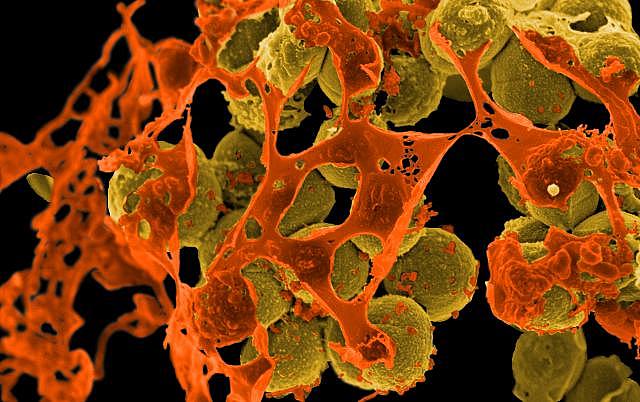

MRSA bacteria.

A new study declared the average everyday home a prime reservoir of drug-resistant bacteria MRSA.

We’ve long known that people could get MRSA outside of healthcare settings, but this study – a genetic analysis tracing MRSA back several decades in New York City – is getting attention because of the extent of its conclusions.

For reporters, it’s an opportunity to think about how we write about the infections.

First, here’s what the study found. Anne-Catrin Uhlemann at the Division of Infectious Diseases at Columbia University Medical Center in New York and her colleagues published the paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“During the last 2 decades, community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) strains have dramatically increased the global burden of S. aureus infections,” they wrote. But the dominant strain’s “evolutionary history and basis for biological success are incompletely understood.”

So Uhlemann and her team sequenced the genome for the CA-MRSA bug found in northern Manhattan, a strain known as USA300, and started looking for patterns. They then mapped how the bug appeared to be mutating and spreading in different neighborhoods. Importantly, they “observed that most USA300 isolates had become endemic in households, indicating their critical role as reservoirs for transmission and diversification.”

As a reporter, this should be exciting news because it takes the superbug story out of the hospital – where we tend to point our fingers and say “Fix it!” – into homes, where the dynamics become much more complicated. Regardless of where the infections began, if they are thriving and spreading in homes, suddenly people who live all around you become characters in your next story. As does MRSA itself.

How did this happen? The study provides one possible answer. They wrote:

Our study also revealed the evolution of a fluoroquinolone-resistant subpopulation in the mid-1990s and its subsequent expansion at a time of high-frequency outpatient antibiotic use.

Fluoroquinolone is a type of antibiotic that was first introduce in the late 1980s and became very popular in the 1990s. As people took more of these antibiotics – often for common colds or other problems – the staph bacteria on their bodies became more resistant to the antibiotics. Even when antibiotics are properly prescribed, people take an antibiotic for a short period and don’t finish out the prescription. They start to feel better, so they stop taking the pills. That allows the bugs to regroup and get stronger.

Fluoroquinolones have been super effective at making people feel better – sometimes simply by conferring peace of mind – and, in doing so, they also appear to have driven the rates of MRSA up, up, up, according to the authors. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lists nine fluoroquinolones currently approved for use:

Norfloxacin, 1986

Ciprofloxacin, 1987

Ofloxacin, 1990

Enoxacin, 1991

Lomefloxacin, 1992

Levofloxacin, 1996

Trovafloxacin, 1997

Gatifloxacin, 1999

Moxifloxacin, 1999

And right there you have nine new characters for your next MRSA story. How have prescribing patterns coincided with this rise in MRSA infections? Can you follow Uhlemann’s lead and trace prescriptions back to certain doctors or clinics? Can you poll a neighborhood and find people willing to take you on a journey through their prescription records to find out how often they have used these antibiotics, and others?

You may be a character in this story, too. Did you bring Cipro – as I have done many times – on your last international trip? Did you take a few and then throw the bottle away? Is the bottle still in your medicine cabinet? Are you unwittingly inviting MRSA into your own home, offering it a beer and letting it sleep on your couch?

"This, once again, argues for the careful use of antibiotics," Uhlemann told HealthDay reporter Amy Norton.

It also argues for more careful reporting about MRSA. We write about antibiotic overuse and the spread of superbugs often as if they are strictly side effects of a lax, bottom-line-focused health care system. As with many aspects of health, though, there is an important social dynamic that we need to take into account. There are individual decisions being made by patients, by parents, by doctors, by administrators, and a range of other players. And the MRSA story can become all the more interesting and impactful – if we tell it right.

Photo by NIAID via Flickr.