How to assess cancer risk: talk to a genetic counselor

Melody Perpich is one of my closest friends. We met during my smoking days. We were in our twenties, just getting started in our careers, buying our first condos in the same building near Lake Michigan, and always on the lookout for fun, handsome and intelligent men.

Those were the days! Like most smokers, I never expected to contract Stage 4 lung cancer. And I never could have guessed Melody would be at my side as a medical advisor when it happened.

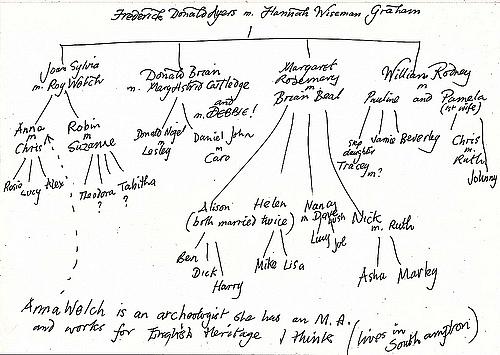

Today, Melody is a genetic counselor who developed The Cancer Risk Evaluation Program at Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center in Chicago. She draws out a pedigree, or a family tree, that helps her patients assess their cancer risk, and also helps them decide what medical tests to get. The information also provides siblings and children information they need to reduce their own risks.

A reader of an earlier blog post recently commented about the stigma associated with lung cancer.

“People may not say it – but they think, ‘You contributed to your own disease,’ in a way that does not apply to other cancers,” the reader wrote.

I have felt that guilt myself. Melody must have sensed it over dinner recently. She told me she doubted that my lung cancer was chiefly due to the smoking habit I abandoned 16 years ago. Not at my relatively young age of 50.

She told me that she believes I must have a gene, or a combination of genes, that easily become damaged by exposure to carcinogens, whether cigarette smoke or other environmental factors.

Melody knows there is a lot of cancer in my family tree—a diagnosis practically on every branch. My mother’s dad, a long-time smoker, died of lung cancer in his 70s. My mom’s mom, a non-smoker who lived with one, died of stomach cancer in her 60s.

In fact, on the very day I got my cancer diagnosis my mom’s brother succumbed to leukemia. My seemingly indestructible uncle, George Saimes, spent a long career as a professional football player, only to spend his later years trying to stave off the illness.

Cancer claimed some of my non-smoking aunts and uncles on my dad’s side, too. Last September, my father, at 83, underwent surgery to remove a cancerous tumor from his lung. My dad quit smoking when he was about my age, having smoked for about 30 years, and he had the same cancer I do, called adenocarcinoma, but his was caught before it spread.

Melody offered to draw me a pedigree. This would benefit my two younger sisters, both in their 40s, and my children, who are now 11 and 14 years old, as well as other relatives.

So how do you draw a pedigree?

The first step, she says, is to identify the historians in your family to gain insight into the medical history of your relatives. This information should include all causes of death, ages of cancer diagnosis, and types of cancer, as well as any other health conditions that run in the family. If possible, obtain death certificates, pathology reports and medical records regarding cancer to verify the diagnosis, she says.

Details are needed from both the maternal and paternal sides of the family, as both have repercussions in a risk assessment. Melody’s family pedigrees sometimes extend to great aunts and great uncles, as well as cousins. Age of diagnosis is particularly important because age is the top risk factor.

She fills the diagram with shaded and unshaded circles and squares, with squares representing males and circles for females. The unshaded shapes represent unaffected individuals, and shaded shapes represent those with cancer.

Here’s a tool from the U.S. Surgeon General called “My Family Health Portrait,” which can get the process started. It’s free and can be shared among family members.

When people get a cancer diagnosis, some go into shock and others go into a mad search for information. Obtaining a genetic analysis may help, and you can find a genetic counselor by going to the National Society of Genetic Counselors website at www.NSGC.org.

The genetic tree answers a lot of questions for the patient, as well as for family who must mix their care for the stricken with an understandable concern about where the cancer came from–and who might be next.

In my next post, Melody talks about the history of high-risk women getting double mastectomies and her take on Angelina Jolie’s decision to get one.

This article has been reposted with permission from the Thompson Reuters blog "Cancer In Context."

Follow me on Twitter @DLSherman

Image by danja via Flickr