How I reported on the double pandemic of COVID-19 and domestic abuse among undocumented women

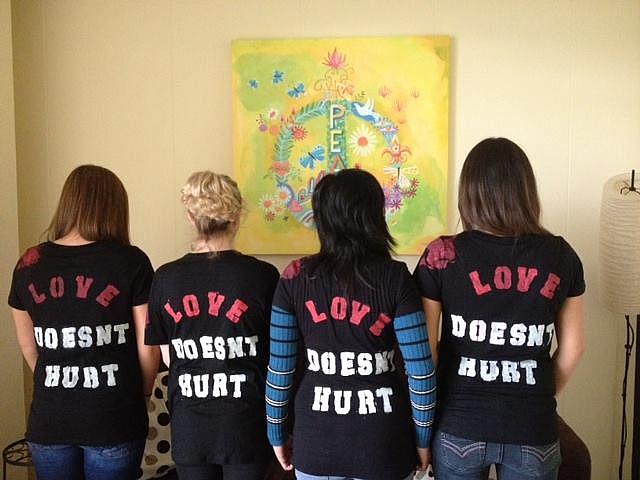

“El amor no debe doler,” or “Love shouldn't hurt” read the T-shirts promoting a clinic to support victims of domestic violence.

(Photo courtesy Francisco Castro)

When cities and counties across the U.S. ordered lockdowns, closing schools, government agencies, and all sorts of community organizations, they were doing it to protect people from catching the coronavirus and lessen the impact of a pandemic.

But for many undocumented women, staying home with no one and nowhere to turn left them unprotected against another pandemic: domestic violence.

Uncertainty about the future amidst the most terrible health crisis in a generation, incredible financial pressures during one off the worst economic periods in American history, and confinement with no external outlets were the perfect mix for a worsening of abuse.

Calls to Los Angeles County Domestic Violence Council Hotline in 2020 rose 43% from the year before.

Yet shelters that managed to keep doors open on a limited basis and other organizations that provide services to domestic abuse victims experienced declines in people seeking their help at the peak of the pandemic. The reason was simple and logical: How can victims seek help when their abusers are at home constantly watching over them?

Grassroots organizations that deal directly with undocumented women who are victims of domestic violence had to change their strategies, creating new codes and finding new ways to assist victims, who never stopped calling when they managed to find a way to do it.

Shelters and other organizations that were forced to close their doors turned to online classes that were both a blessing and a burden. Many of the people who needed the help didn’t have internet access while others found it easier to connect for help without having to worry about traveling to a specific place or whom to leave their children with.

The pandemic also came at the tail end of an administration that had made anti-immigrant rhetoric one of its mainstays. Undocumented immigrants who had been increasingly receding into the shadows for years became nearly invisible. Their plight became secondary as the country dealt with the pandemic and a presidential campaign.

U.S. Customs and Immigration Services reported that petitions under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), which allows survivors of domestic violence to gain lawful permanent residence, whether or not they entered the U.S. legally, provided the abuser was a citizen spouse, increased steadily from 9,400 in the 2016 fiscal year to 14,900 in fiscal year 2020.

However, U visa petitions, which allow undocumented victims of violent crimes to live and work in the U.S. for four years, declined by nearly half, from 61,700 in fiscal year 2017 to 36,200 in fiscal year 2020. And the waiting lists to receive these grew substantially as government agencies suspended services during the pandemic.

One of the victims of domestic violence I spoke with has been waiting years for a U visa.

In my case, finding her and other undocumented women who were victims of domestic abuse was a matter of luck and perseverance.

The organizations that help victims were or are still operating in limited capacity. Some have returned to partial in-person services, others have not.

Cold calling was paramount. Many calls were never answered. As a freelancer, it’s sometimes more difficult to get a call back because one doesn’t have the backing of a recognizable media organization.

But when I did manage to talk with someone, they proved useful and were willing to help.

In one instance, after I talked to the director of an organization, a woman who had sought their help called soon after I did to tell them she wanted to share her story to help others in similar situation. Even the director was taken aback when she called me minutes later to put me in contact with her.

The victims of domestic violence I spoke with were very open to tell their stories. None of them had ever shared them with the media, and for some it was another step in their long recovery. They all admitted that the abuse had had long-lasting effects on their lives and even years after the suffering, the psychological wounds are still very much fresh, even if the physical injuries have disappeared.

One thing I can recommend to others who deal with these projects is to start early and set small goals with specific dates. And stick to them.

For me, it was something like: “This week I’m going to make so many phone calls and I will send so many emails to get this particular information.”

Little by little I began to fit together all the pieces in the puzzle that were my stories.

Something else I would recommend is to start writing the articles once you have some pieces of the puzzle assembled. Only that way do you figure out what you’re missing and what you need to get to make them whole.

That gives you time to continue researching the subject and order your thoughts.

It’s also important to seek direction from your mentor early and often when you find an obstacle or simply want reassurance that you’re on the right path. They can point to resources or suggest ways to overcome those issues, and give you guidance.

My mentor was also gracious to offer her editing skills. That was incredibly helpful. As a freelancer, I work alone without any input or collaboration from others, so to have a more experienced and knowledgeable second set of eyes really helped hone my arguments and cut things that were unnecessary or expand certain points further.

The result was a three-part series that I believe gives voice to those too often without a voice, which is exactly what I sought to do when I began this project. The publication where the stories published—the Spanish-language Excelsior Newspaper—has a 390,000 weekly distribution across Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

Because of fear, lack of knowledge, and cultural factors, undocumented immigrants often don’t seek the help when they are victims of domestic violence. By providing them with resources and stories that resonate with them I hope to have made an impact in their lives.